by James C. Sherlock

Granby Street Norfolk after Great Hurricane of 1933

So how do we picture how bad a hurricane or Nor’easter could be along Virginia’s coast? What might it look like?

Won’t the Outer Banks catch the worst of any hurricane and break it up?

Well, no.

Consider some stunning historical examples.

The storms of the Eighteenth Century

The entire 18th century was replete with storms that ravaged the Virginia coast and rivers that drain into the Chesapeake.

Twenty six of them. Read about them.

Astonishing stories.

In one, you will read that on October 16, 1781:

“A storm of “unknown character” struck Virginia. The Earl of Cornwallis, at Yorktown, was trapped by the French Fleet and the Patriot Army, under the command of George Washington. The Earl decided to flee to the north to Gloucester Point under the cover of darkness. A “furious storm” doomed the plan to failure, as seas ran high and every boat was “swamped.” He sent forward his flag of truce and surrendered, thus ending the battle.”

In another:

“September 22-24, 1785: The “most tremendous gale of wind known in this country” passed over the Lower Chesapeake Bay and went along a track very similar to the Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane of 1933. At Norfolk, lower stories of dwellings were flooded. Warehouses were totally carried away by the storm surge, causing large amounts of salt, sugar, corn, and lumber to disappear. A large number of cattle drowned, and people hung onto trees for dear life during the tempest. At Portsmouth, the entire town was submerged.

Forrest’s book, Sketches of Norfolk, offers this account of the storm: “This year, 1785, was noted for the highest tide ever before known to Norfolk, completely deluging a large portion of its site on the water side.”

Almost all ships in the area were driven from their moorings near Norfolk. Many ships were dismasted as well. The brig Nancy, coming from Madeira with a cargo of wine, was dashed to pieces on the Virginia Capes. Only two aboard survived the ordeal. The sloop Phoebe lost its bowsprit and was laid upon her beam ends. A Dutch ship was found fully loaded, with no one aboard. Vessels floated inland into cornfields and wooded areas. No less than 30 vessels were seen beached after the storm. Damages totaled £30,000. At least two died due to shipping disasters. After ravaging Virginia, the system tracked up the coast to Boston.“

Willoughby Spit and the Hurricane of 1749

A fierce hurricane in 1749 drove the water in the Chesapeake to rise to 15 feet above normal.

It destroyed Ft. George located at or near the site of what is now Ft. Monroe. A large airborne tree and its root ball breached the outer wall of the fort on the land side. Water breached and destroyed both the outer and inner walls of the fort on the Bay side.

It was so strong that it formed Willoughby Spit, the eastern terminus of the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel just north of the Naval Base Norfolk.

Bodies from shipwrecks washed ashore for days.

Willoughby Spit after Isabel

In 2003, Hurricane Isabel tried to take Willoughby Spit back. Isabel destroyed the protective beach berm, nearly three quarters of the protective sand dune, and several dwellings. The Corps of Engineers Willoughby And Vicinity Storm Damage Reduction Project, the largest single storm damage reduction project in the City of Norfolk, was completed in 2017.

We literally can’t withstand another century of storms like the 18th without modern flood protection systems.

The Great Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane of 1933

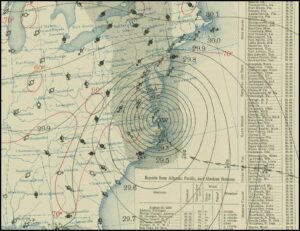

Surface map for August 23rd, 1933 at 8 AM, EST

The worst storm in the past 100 years was the Great Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane of 1933.It was a killer.

As with so many storms, it wasn’t the strength of the 1933 winds so much as the path of the eye that caused the widespread damage. The eye passed directly over Norfolk, moved north along the Chesapeake and veered slightly inland up the Rappahannock and crossed the Potomac River near Colonial Beach.

It caused nearly 10 feet of storm surge at Norfolk’s Sewell’s Point. The highest point in Norfolk is the runways of the airport at 12 ft.

Four feet of flooding along the York River.

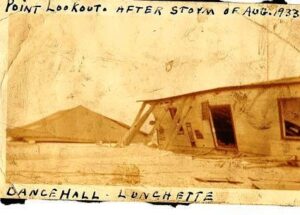

Point Lookout at the mouth of the Ware River after 1933 hurricane

The storm inundated all the low lying areas along the Potomac. Eight feet of flooding along U.S. 1. in Alexandria. It knocked a train off of the Anacostia River bridge in D.C. Created an inlet that turned Assateague into an island.

Thirteen inches of rain and 47 bridges destroyed in York County Pennsylvania.

That sort of thing.

Bottom line

Widespread destruction and loss of life along Virginia’s coasts and rivers is not theoretical. It is assured if we don’t take action to protect ourselves. As shown by the 18th-century storms, no argument over climate change is relevant.

The Commonwealth, as described in yesterday’s column, is on the wrong track entirely.

Perhaps the Department of Conservation and Recreation can be sobered by this recounting of our history with storms.

But I doubt it will matter.

Even sober they have no idea what they are doing.