by James A. Bacon

In the absence of Standards of Learning (SOL) exams last year, there’s no way to tell if the education policies enacted by the Northam administration are working or failing for the vast majority of Virginia school students. But Virginia schools did administer the SAT college-preparatory exams, so we can get a sense of how well high school graduates are doing.

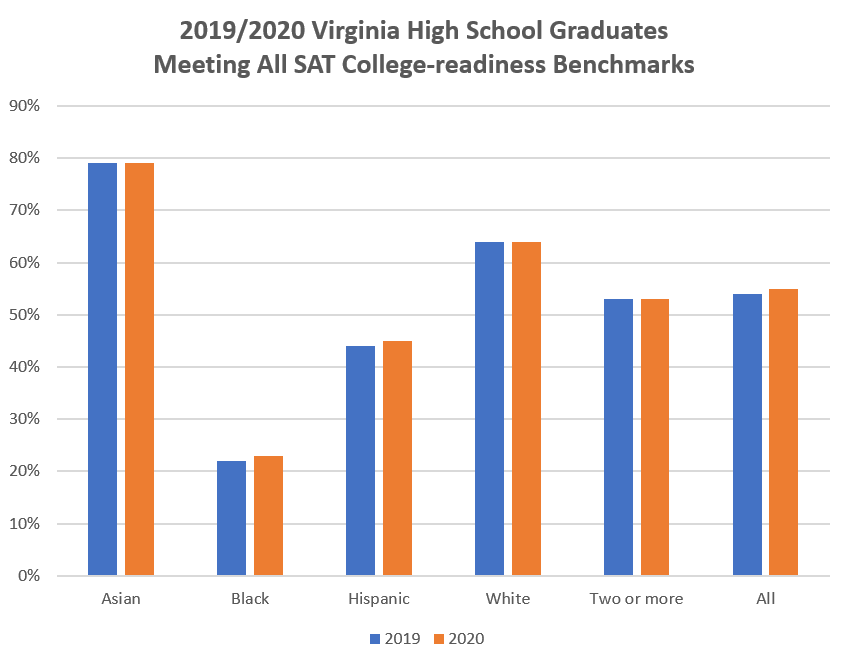

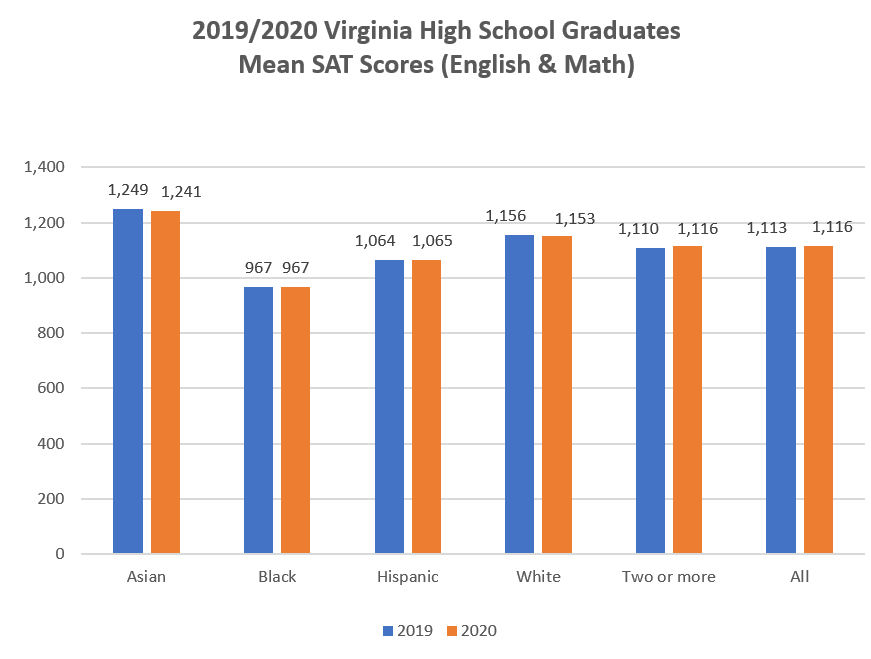

The good news is that Virginia high school grads eked out incremental gains in the percentage that met or exceeded the College Board’s college-readiness benchmarks in English and mathematics. The bad news is that a wide gulf persists between Asians and other ethnic groups, even though the average scores of Asian students declined somewhat.

Fifty-five percent of Virginia high-school graduate test takers met the SAT college-readiness standards, up from 54% last year. (The Virginia Department of Education rounds off its numbers, so it is impossible to tell if the increase was a full percentage point, or slightly more, or slightly less.) As usual, Asian students out-performed all other racial/ethnic groups by significant (though diminished) margins. Whites trailed Asians, Hispanics trailed whites, and blacks trailed Hispanics.

“Despite the disruptions caused by the closure of schools, Virginia students continue to perform well in comparison with their peers nationwide,” said Superintendent of Public Instruction James Lane in a press release. “But the wide gaps we see in the performance of student groups underscore the importance of the work underway at both the state and local levels to promote equity and expand opportunities for underserved students. Closing these persistent achievement gaps is the number one priority of both the Virginia Department of Education and the state Board of Education.”

While Virginia high schoolers continued to out-perform their peers in other states, the superior margin in average SAT scores shrank last year. The combined average for English and math tests rose three points for Virginia students to 1,113. By contrast, the average rose for students nationally by 12 points to 1,051.

(Warning: It is dangerous to draw any hard conclusions from the change in year-to-year performance, just as it is to draw conclusions from changes in state-to-state comparisons. A major variable in statewide-average SAT scores is the percentage of students taking the exams. In Virginia 65% took the exams this year compared to 68% last year, a decrease of three percentage points — enough to influence average scores. Students taking the exams tend to be more academically qualified for college than those who don’t.)

Regardless, the chronic under-performance of African-American students remains a stubborn and indisputable fact, despite the emphasis the Northam administration has given to closing the gap.

Also worrisome is the fact that insofar as the racial/ethnic gap closed slightly this year, it mostly reflects declining Asian and white test scores, not an increase in black test scores. (Hispanics increased their average overall SATs by 1 point.)

Bacon’s bottom line: Virginia’s educational policy under the Northam administration has been premised on the assumption that schools are systemically biased against “people of color” while whites are favored by “white privilege.” In the social-justice catechism, Asians are deemed to be people of color. Social-justice orthodoxy fails to explain why Asians excel in a system supposedly stacked in favor of whites. Social-justice orthodoxy also fails to explain why Hispanics, who labor not only under the supposed disadvantage of ethnicity but the very real disadvantage in many cases of speaking English as a second language, out-perform blacks. Moreover, leftist orthodoxy ignores the fact that spending per student tends to be higher for blacks in Virginia than for whites.

Northam’s educational policies have a two-fold thrust: (1) to implement a “restorative justice” approach to school discipline, (2) to spread the social-justice doctrine of systemic racism and white privilege, and (3) to increase state support for K-12 education. The social-justice paradigm refuses to consider the possibility that the vigorous enforcement of social-justice priorities might have negative consequences on blacks such as increasing classroom disruption or inculcating a sense of passivity and helplessness in the face of supposedly omni-present racism.

One can speculate whether Northam’s policies are making a difference in the lower grades. But the SAT scores suggest that there is little sign of improvement among college-bound seniors.