Once upon a time in a galaxy far far way, it was considered a great honor among 4th-year University of Virginia students to be selected for residence on the Lawn — the architectural heart of the university designed by Thomas Jefferson and now designated a world heritage site. The accommodations were less than luxurious — most memorably, the 47 rooms were not equipped with their own bathrooms. There were offsetting advantages. The rooms had fireplaces, and the University provided a plentiful supply of wood. But living on the Lawn was mainly about status. It conferred recognition of a student’s accomplishments in his or her first three years.

Something is happening at UVa, and I don’t fully understand it. The prestige of a Lawn residency is declining. The trend was made visible last year when a 4th-year woman posted a prominent sign on her door emblazoned with the words “F— UVA” and in subsequent statements dismissing founder Thomas Jefferson as a slave-holder and a rapist. As evidenced by supporting signage on other doors, other Lawn residents shared her sentiments.

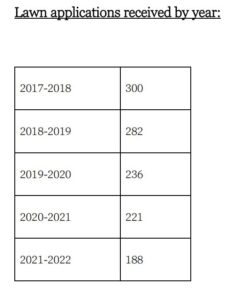

But the decline in prestige long precedes that particular expression of animus toward the university granting the honor, and it precedes even the reign of wokeness under current President Jim Ryan. As shown in the table above, submitted by UVa in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by UVa alumnus and Bacon’s Rebellion contributor Walter Smith, applications to live on the Lawn have fallen steadily and precipitously — 37% — over the past five years.

I have not studied this issue closely, so any conclusions I state here are preliminary and tentative. But I would suggest that the decline in interest in Lawn residency reflects the larger downgrading of the university’s Jeffersonian legacy and its traditions by the administration, faculty and, downstream, of the students. In not merely apologizing for but wallowing in UVa’s slave-holding and segregationist past, UVa leaders have effectively de-legitimized their own institution. When the university expunges the names of ancient benefactors from buildings, and when controversies arise over the racist implications of everything from the famed serpentine walls (which supposedly hid slaves from view) to the curves in the athletic V-sabre logo (which evoke the serpentine walls), the administration has systematically devalued the university’s history and traditions while doing nothing to uphold them.

Ironically, even as the administration, faculty and activist students bemoan the racism of UVa’s past, 60% of the students offered the prestigious slots this year were “students of color,” in the university’s nomenclature. There is a strong possibility that the Lawn selection process has been biased to favor non-whites. For instance, 22% of all offers extended this year went to African-American students, who comprise only 7% of the student body. Whites, comprising 59% of the student body, received only 40% of the offers.

The University does not provide the racial background of the applicants. But I would conjecture that the decline in applications has been most pronounced among whites, who have concluded, not without foundation, that the odds are stacked against them. Many whites at UVa are retreating from the oppressive wokeness around them.

Traditions do need to evolve with the times, as does our understanding of the past. UVa’s connection to slavery and segregation were long swept under the rug. It is right to exume painful history so that we may learn from it. But UVa is throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. Acknowledging the past has morphed into cultural cleansing. UVa is distinctive among U.S. public universities in the richness of its heritage and traditions. Without them, UVa is just another state university competing on the basis of its wokeness.

That is not a formula for greatness. The declining interest in living on the Lawn is silent witness to the self destruction of a once-renowned institution.