by James A. Bacon

Proponents of Smart Growth, of whom I am one, have been arguing for several years that Americans embarked upon a fundamental shift in driving habits beginning in the mid-2000s. So marked was the decline in Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) that a certain triumphalism set in — the drop in driving signaled a shift back to mass transit and walkable urbanism. To be sure, some of the downturn could be attributed to the slow economy, but profound changes in values — a rejection of auto-centric development — was taking root. Some commentators went so far as to proclaim that America had reached “peak car,” and predicted that VMT per capita would continue to decline.

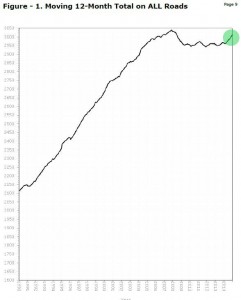

Well, the Federal Highway Administration has reported the latest numbers for 2014, and that triumphalism doesn’t seem quite as justified as it did a couple of years ago. Cumulative travel (measured by the moving 12-month average of Vehicle Miles Driven) increased 1.7% last year, bringing the total travel to a point just shy of the record in 2007. Even more worrisome, drivers were really on a tear at the end of the year. Traffic volume in December increased by 5% compared to the same month the year before.

I haven’t seen how other Smart Growthers have spun this data, and they may have interpretations that confirm their conviction that a big re-set is occurring in human settlement patterns. But I regard the data as grounds for re-examining some of my long-held beliefs — not to change them necessarily, but to go back and take a fresh look and see if they still hold up.

Clearly, the pick-up of the economy and increase in the number of jobs is a factor in putting Americans back on the road. More jobs means more commuting. The plunge in the price of gasoline toward the end of the year undoubtedly played a role as well — the increase in driving was particularly pronounced in the latter months of the year when motorists were enjoying the benefit of lower gas prices.

It’s also possible that the much-touted shift in development back to the urban core is less pronounced than commonly stated. There is no denying that the momentum of growth and development has shifted to some degree back toward traditional downtowns and urban neighborhoods. Downtowns are reviving. They are gaining population and jobs, in a reversal of a decades-long decline. But growth and development also continues in outlying suburbs.

I continue to believe that there is a strong unmet desire in the marketplace for walkable urbanism. But I’ve come to realize two things. First, there is a limited capacity for urban jurisdictions to accommodate new growth. Older cities have limited land available for infill, and re-development of existing commercial and residential areas is a slow, incremental process that takes place property by property and is limited by NIMBY resistance to greater density.

Second, the Suburban Growth Machine is still intact, even after the devastation of the 2007 real estate crash. There is still a vast reservoir of suburban land zoned for traditional, suburban-style development. It is still far easier to build large-scale projects in the burbs than it is in urban areas. Developers are adapting by building more urban-lite projects — mixed-use with some walkability thrown in. Rarely is this development transit-friendly (although there are exceptions, such as locations along the new Silver Line in Northern Virginia). The problem is that these nodes of mixed-use walkability are scattered across the suburban landscape. They rarely connect. Accordingly, they do not achieve the critical scale required to truly change peoples’ lifestyles and reduce driving to a significant degree.

Bacon’s bottom line: I still maintain that we’ve bent the curve of the once-relentless increase in Vehicle Miles Traveled. While total VMT is nearing its previous peak, VMT per capita still remains considerably below the peak. My new modified position is that driving will continue to increase but on a slower growth trajectory than in previous decades. We’ll see how that prediction stands up to real-world data.

What about Virginia? The FHWA report provided a breakdown of travel by state for December 2014. Compared to the national increase of 5.0%, VMT in Virginia increased only 3.5%. Does that slower growth reflect Virginia’s laggard economy or something more profound? Stay tuned.

Update: Darin, who identifies himself as the ATL (Atlanta) Urbanist, tweets that the spike in VMT may be tied a marked increase in the size of the working age population. View thegraph here.