by James A. Bacon

I turn 62 years old today, and one of the few perks of advancing age is the prospect of collecting Social Security. I, like thousands of other Baby Boomers who turn 62 every day, face the decision whether to start pocketing Social Security now, wait until full retirement at 66 or delay taking benefits even longer in the expectation of bigger checks down the road.

The conventional wisdom is that it makes sense to wait to 66, or even older if you can, because each year you delay, your SS benefits increase by roughly 8% to compensate for the actuarial reality that you’ll have one year less to collect before you die. If you’re in good health and expect to live longer than average life expectancy for male 62-year-olds — 83.8 years — delaying retirement is an especially good idea.

But what if you don’t have faith in the system to deliver on its promises, as I do not? What if you share the widely held belief that, barring heroic action by Congress, that the Social Security Trust Fund will run out by 2030? If the trust fund runs dry, the system can pay out no more than it brings in through payroll taxes, or about 75% of current promised levels.? Should we adopt the attitude of take the money and run? Get what’s yours while you can?

It’s a big decision, so I punched some numbers into a spreadsheet to see how the Retire-at-62 scenario compares to the Retire-at-66 scenario. (The numbers below are rough estimates only, not official Social Security Administration estimates.)

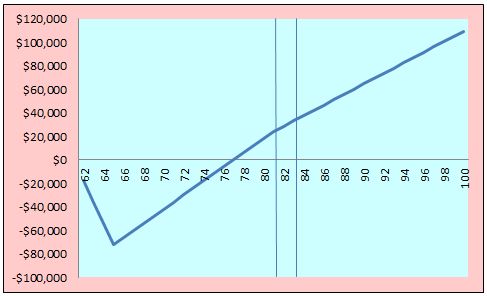

This chart compares the cumulative payout under a Retire-at-66 scenario receiving $2,000 per month or $24,000 per year compared to a Retire-at-62 scenario of $1,500 per month or $18,000 per year.

Waiting until 66 means no Social Security income for the first four years. During that period, you’d end up a cumulative $72,000 in the hole. But then, beginning at 66, your annual payout would be roughly $6,000 per year higher. You’d whittle away at that $72,000 hole until, at age 77, you broke even. After that, you’d be ahead of the game by increasingly large margins each year.

Then comes Boomergeddon. Around 2030 — the left vertical line — the trust fund runs out of money and Uncle Sam reduces the payout to what it brings in through payroll taxes, or about 25%. (The actual number would vary, depending upon economic and employment conditions.) In one sense, you’re screwed — you’re getting less than promised. But you’d be screwed if you retired early, too. You’d still be ahead of the game compared to retiring at 62 — just by a smaller margin, ahead by only $4,500 per year instead of $6,000 per year.

If you live until 83.8, your life expectancy at 62 years old today — the right vertical line — you’d still be ahead. If you’re healthier and more long-lived than average and live past 83.8 — and half of all males do — then the cumulative payout surpasses the early retirement scenario by an increasingly large margin.

This calculation does not take into account inflation, but that’s a non-factor because the Social Security program adjusts the payout each year to reflect the higher cost of living. Neither does it take into account the time value of money. A dollar earned in 2015 is much more valuable than one earned in 2030. That’s especially true if you actually save your money and earn a return on your investment. But most people (including me) don’t anticipate saving money during retirement; they anticipate spending down some or all of their savings. They view Social Security payments as income to be spent. Thus, the time value of money really has no application here.

What if, as I argued in my book “Boomergeddon,” Uncle Sam changes the payout in a Boomergeddon scenario to make Social Security even more of an income-redistribution engine than it already is? People living on the margin, say $1,000 a month, live a marginal existence as it is; they would truly suffer if their payments were cut when the trust fund is exhausted. There is a high degree of probability that politicians would give low-income households smaller cuts and take the balance out of the hides of higher-income households. But that still doesn’t change the bottom line that most middle-class Americans would be better off retiring at 66 — they would be better off by a smaller margin. Anyone with a lick of sense would anticipate the possibility of changes to the payout formulas and adjust their lifestyles accordingly, but the prospect of Boomergeddon shouldn’t change the decision when to retire.

The critical variable influencing your retirement-age decision is your health. If you have diabetes, untreated hypertension, a high risk of cancer or other health threats, you have worse odds of making it to 83.8 years old. Even then, you’re not necessarily well advised to take the money and run. The break-even year is 77. If you live older than 77, you’d still come out ahead delaying your retirement.

For many people, the discussion is purely academic. If you’re working a full-time salaried job, it probably makes sense to continue working, generating income and letting your Social Security retirement benefits gain value. But there are plenty of sixty-plus people who have lost their jobs, find themselves working part-time or have fluctuating free-lance incomes for whom that Social Security income might look pretty good. Those would be well advised to think carefully before making the leap.