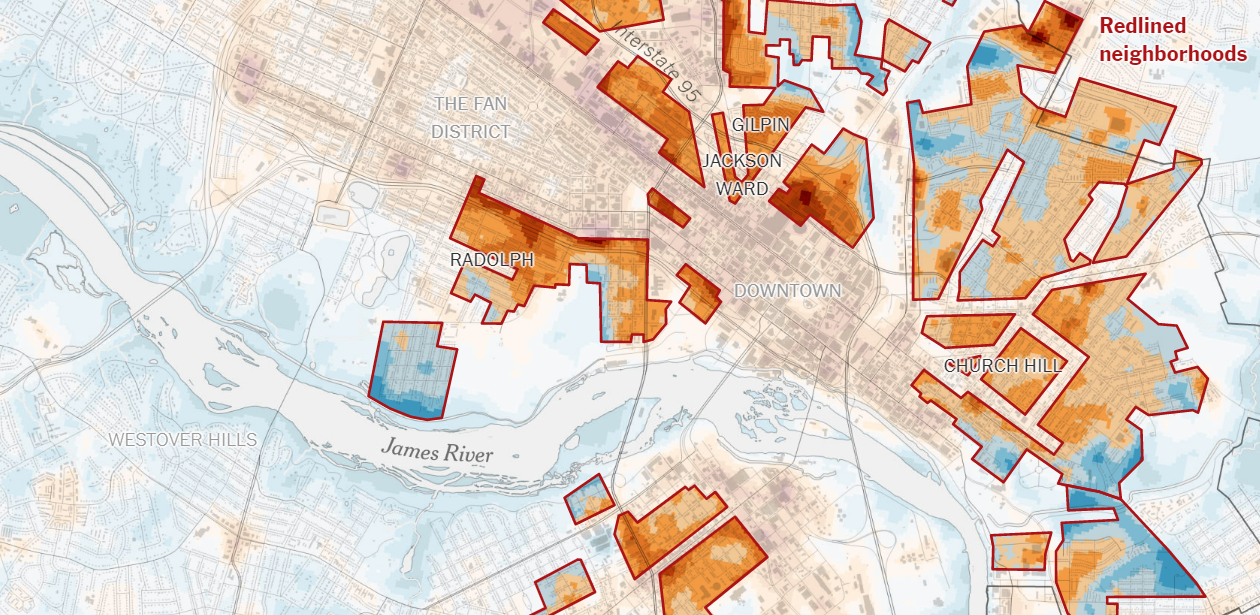

The New York Times has drawn a straight-line linkage between the redlining of neighborhoods in Richmond nearly a hundred years ago and the fact that African-American neighborhoods have higher average temperatures than mostly white neighborhoods. Black neighborhoods, often comprised of public housing, have fewer trees “to shield people from the sun’s relentless glare.” Writes the NYT of Richmond’s Gilpin Court housing project:

More than 2,000 residents, mostly Black, live in low-income public housing that lacks central air conditioning. Many front yards are paved with concrete, which absorbs and traps heat. The ZIP code has among the highest rates of hear-related ambulance calls in the country.

There are places like Gilpin Court all over the United States where neighborhoods can be 5 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter in summer than wealthier, white parts of the city, the Times says.

And there’s growing evidence that this is no coincidence. In the 20th century, local and federal officials, usually white, enacted policies that reinforced racial segregation in cities and diverted investment away from minority neighborhoods in ways that created large disparities in the urban heat environment.

It’s certainly true that there was redlining in the 1930s, and the NYTimes makes a good case that many of the redlined neighborhoods remain predominantly African-American today. Trouble is, when you interpret everything through the lens of race, every disparity looks like a racial inequity.

The actual causes of heat map disparity might be socioeconomic in nature: some groups have more money. Or they might be political in nature: some groups have more political clout in city hall. Or they might be due to lousy planning by do-gooders who failed to anticipate unintended consequences when they designed housing projects. But when you’re a New York Times reporter, it’s always about race and racism.

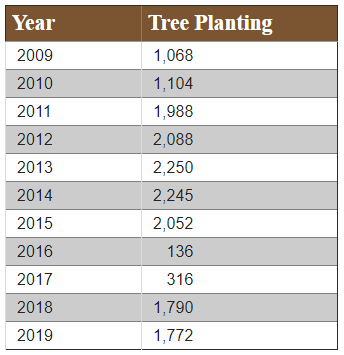

The key link between racist housing policy and high temperatures is tree cover, or lack of it. As it happens, the city has an Urban Forestry Division (UFD), which, according to its website, is responsible for planting approximately 2,000 new and replacement trees a year. The UFD also does pruning and removes dead trees. Municipal resources are supplemented through a tax-deductible Adopt-A-Tree program.

The website section under the Adopt-A-Tree headline includes the chart seen at right. It’s not clear if it refers to publicly financed tree plantings, Adopt-A-Tree plantings or all tree plantings. Regardless, it’s a significant number of trees.

The city does not have a formal UTC (urban tree canopy) goal. But the city is trying to maintain at least 65% of identified planting sites on city-owned property. Somehow, the NYTimes manages to write an article about tree coverage in Richmond without once mentioning the city’s tree-planting program and what criteria the city uses for allocating tree plantings.

While the article makes a big deal about the lack of trees in public housing projects, the report never asked how public housing came to be so devoid of trees. Gilpin Court has grass lawns — why no trees? Did the public housing authority never plant trees, due perhaps to budgetary constraints? Did the public housing authority try planting but the trees but they died, due perhaps to neglect? If the housing authority had no money for trees or tree maintenance, what does that have to do with redlining? How is this a failure of anyone but the housing authority?

The article states that neighborhoods with white homeowners “likely” had more clout “to lobby city governments for tree-lined sidewalks and parks.” It presents no evidence whatsoever that white homeowners exercised such clout in Richmond.

However, the article does make this astonishing observation: “Tree-planting can be politically charged. Some researchers have warned that building new parks and planting trees in lower-income neighborhoods of color can often accelerate gentrification, displacing longtime residents.” In other words, whatever political influence is being exercised could be African-American militants trying to keep out trees and parks!

At no point does the Times describe any policies since redlining that “diverted investment away from minority neighborhoods.” To make such a statement requires a willful act of ignoring the millions of federal dollars steered into Richmond’s urban redevelopment projects.

Nor does it occur to the Times reporters that perhaps residents of inner city neighborhoods use their influence at city hall for things other than trees and parks. Perhaps African-American residents in poor neighborhoods have different priorities than NY Times reporters — like community centers, or police protection, or new school buildings, or public libraries with Internet connections, or programs for the elderly, or faster fire-and-rescue response times, or pothole repairs, or better bus service, or mental health and substance abuse services.

The reporters argue somewhat plausibly that former redlined districts were targeted for new industries, highways, warehouses and public housing “built with lots of heat-absorbing asphalt and little cooling vegetation.” But planners didn’t target those areas because they had once been redlined, or even because blacks lived there. They targeted those areas because the real estate was cheap and/or had access to highways. The phenomenon was a socioeconomic one, not a racial one.

There is one other socioeconomic factor to consider here. One of the things people do when they make more money is move to more desirable neighborhoods. One of the things that makes neighborhoods more desirable is the presence of parks and trees. Insofar as white people have higher incomes and net worth on average — a phenomenon that has historical roots in racism but also failed government policies and other factors — one would expect white people (and middle-class blacks) to gravitate toward neighborhoods with parks and trees. This has nothing to do with redlining in the 1930s or, as the NYT headline puts it, “decades of racist housing policy.”

The causes of inequality and inequity are complex. In the United States, a legacy of racism is part of the story and cannot be discounted. But it’s not the whole story by any means. By distracting from more important drivers of inequality, the fixation on race as a mono-causal explanation does more harm than good..