The COVID-19 virus has escaped containment, and it has reached Virginia. Authorities have identified two documented cases of the COVID-19 virus: one a U.S. Marine stationed at Ft. Belvoir who apparently was infected during an overseas business trip, and the other a Fairfax County man in his 80s who picked up the illness on a cruise ship in Egypt.

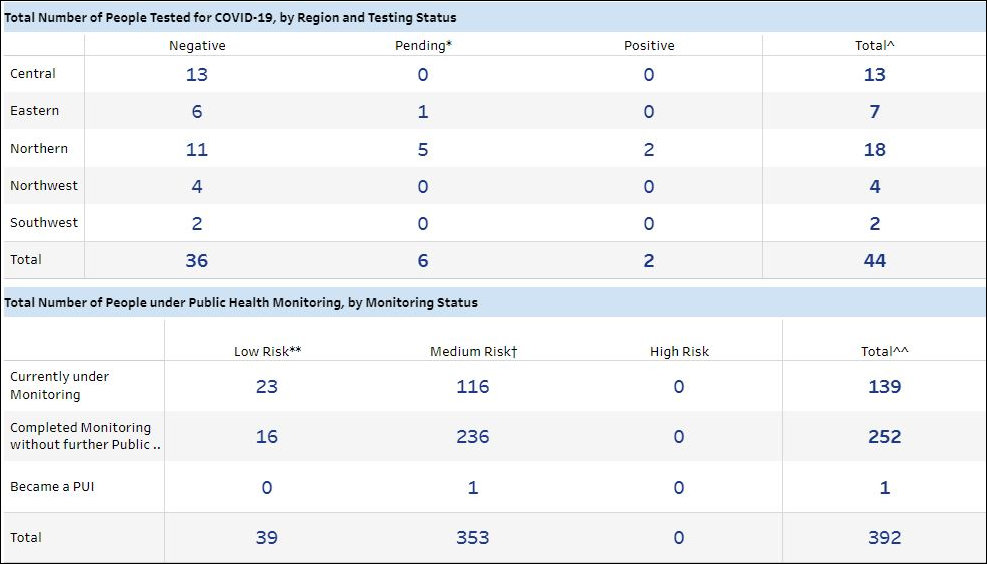

Most likely, the two cases represent the tip of the epidemiological iceberg. People can carry the virus for two weeks without showing symptoms, and the ability of state public health authorities has been hampered by a shortage of testing capabilities. According to the Virginia Department of Health coronavirus website, the state has tested only 44 people to date. The shortage of testing kits, which should be alleviated in the near future, has meant that public health officials have utilized their limited supply sparingly.

In other words, there could be dozens if not hundreds of people infected with COVID-19 today in the Old Dominion, and we just don’t know it. And we likely won’t know until they start showing up in hospital emergency rooms a week or two from now.

In theory, there are other ways to track the spread of the virus, if only indirectly: such as monitoring the number of patients admitted to doctors’ offices and hospital emergency rooms with respiratory ailments consistent with COVID-19 symptoms. If the number of patients reporting respiratory issues is surging above and beyond what is normal for this time of year, we can surmise that COVID-19 is largely responsible. And we can tell where the virus appears to be spreading the most rapidly. Such information can inform local authorities and citizens on the need to take measures such as closing schools, canceling events, and working from home.

Here is the data that appears on the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) website:

From this dashboard, we see that 139 individuals are under “public health monitoring.” “Low risk” individuals include U.S.-based aircrew members and private travelers who have flown through or had layovers in mainland China in the past 14 days. “Medium risk” individuals are those who have traveled from mainland China in the past 14 days. Given the fact that the virus has leaped borders into the United States and Virginia itself, the second table data tells us nothing of remote importance.

It was inevitable that COVID-19 virus would reach Virginia. We live in a globalized economy with porous borders, and within the U.S. we are a hyper-mobile society. Given the nature of the virus — carriers show no symptoms for up to two weeks — people spread the plague unwittingly. It is no accident that the first two confirmed cases occurred in Northern Virginia, the most cosmopolitan and globally connected region of the state. Now that the virus has reached NoVa, it will remorselessly move downstate.

Until someone invents a vaccine, “social distancing” is the only practicable way to slow the spread of the virus. Obvious examples of social distancing are closing schools and colleges, canceling events, and facilitating telework so people can work at home. Also, once people know that the virus is circulating in their community, individuals can self-isolate by limiting their excursions from home and their interactions with others. There is significant economic cost to these measures, however, and we don’t want to succumb to ill-founded hysteria.

In our decentralized system of government, the actions of local medical officials, educators, business managers, community leaders and individuals are as important as those of governors and presidents. To make rational decisions that optimize the trade-offs between limiting the spread of the disease without shutting down the economy, everyone needs the most current possible local information. That information needs to be more granular than it appears on the VDH website, which breaks the state into only five regions.

At present, that real-time information appears to be lacking. We will get more data as testing kits become more readily available. It would be immensely helpful if VDH would display that data in a way that citizens and decision makers can query and map so they can see what is happening in their community.