by James A. Bacon

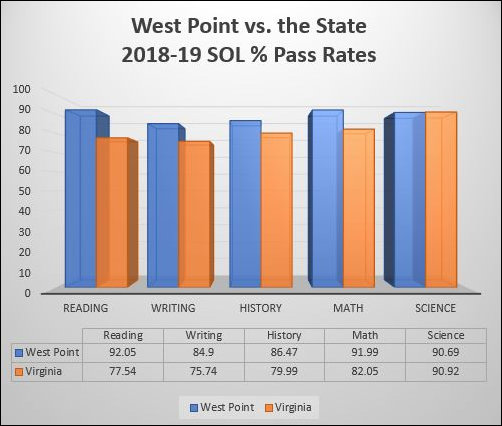

One of the consistently top-performing school districts in Virginia is that of the town of West Point, a Tidewater mill town whose economic mainstay is a paper plant. Somehow, year in and year out, the West Point school district delivers superior results, at least as measured by pass rates in the Standards of Learning (SOL) exams. The table above shows how West Point clobbers the state averages in English reading and writing, history & social studies, and math. What the table doesn’t show, but previous posts on Bacon’s Rebellion have, is that this gritty mill town has the one of the top pass rates of any district in the state.

Here’s one question that you’d think Virginia policy makers would be asking: How does West Point do it? Clearly, West Point is not an enclave of socio-economic privilege. Might the schools there be doing something that other school districts can learn from?

For clues into what is going on at West Point, I turned to the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis (CI) report on K-12 funding trends. (In an earlier post I had criticized the report in a knee-jerk reaction, for which I apologize. The report contains a lot of valuable data.)

Don’t look to state funding. While state aid to K-12 education (adjusted for inflation and the number of students) fell 8% since 2008-2009 across the state, it fell 15% for West Point. The town made up much of the difference with local revenues, but inflation-adjusted revenues were still slightly lower in 2017-18 than in 2008-09. The town invested 264.8% of the minimum required of localities in the state’s funding formula — compared to a 113.3% state average. That was, in school funding lingo, a strong “local effort.”

Despite flat inflation-adjusted funding and a 7% increase in enrollment (40 students), West Point managed to add 12 teachers and instructors, eight support staff, and four more counselor/librarians for a total of 24 more staff. Someone in the school administration must have a sharp pencil to have pulled that off.

West Point does have a demographic advantage. Its students are less poor and have fewer disabilities than the state average, but the discrepancy is modest. According to CI data:

- 5% of all school-age children lived in poverty in 2017 compared to 13% statewide.

- 31% of all students were provided free or reduced- price lunch in 2018-19 compared to 45% statewide.

- 11% of all students had a disability compared to 13% statewide.

West Point schools generated controversy recently when the school board fired a French teacher for his refusal to address a transgender student identifying as a boy by his preferred pronouns. That exercise in political correctness overshadowed the fact that West Point is a high-performing school system.

Fiscal data takes us only so far. The explanation for the West Point phenomenon probably arises from non-fiscal factors.

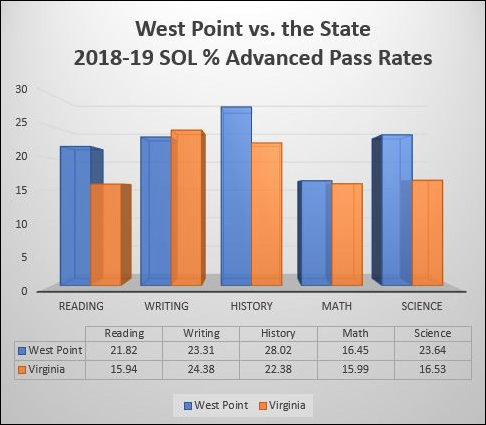

Is it possible that West Point does a better job of teaching to the test — pushing lower-performing students over the line while spending less time and focus on more advanced students? To the contrary. The performance gap between West Point and other school systems is even more marked for “advanced pass” SOL scores, at least for reading, history and science.

I don’t know what West Point’s secret is. The explanation, whatever it is, may discombobulate my pet theories about K-12 education — or it may confound the Victimhood and Grievance Narrative that has become increasingly prevalent in the Northam administration. One of these days I hope to find out.