by James A. Bacon

I’ve tended to think of the housing-affordability issue in Virginia as a phenomenon relegated to the major metropolitan areas. Northern Virginia, Richmond and Hampton Roads are where the population growth has occurred, and that’s where zoning and environmental restrictions have been the most stringent, making it difficult for homebuilders to keep pace with demand. Figure in the higher cost of land, particularly near the urban cores, as well as regulations discriminating against trailer parks and manufactured housing, and it just seemed obvious that affordability would be a bigger issue than in slowly depopulating rural areas where, if anything, housing would be in excess supply.

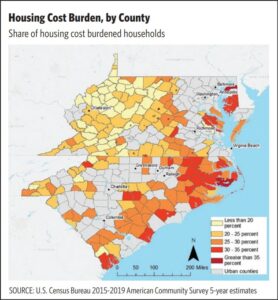

But according to a recent article in the Richmond Federal Reserve Bank’s District Digest, affordability in the 5th District, which includes Virginia, is almost as severe a problem in rural areas as in metropolitan areas.

“In the Fifth District, rural households are only slightly less likely to

be housing cost burdened than urban households,” states an article by Sierra Latham. “Twenty-five percent of rural households at all income levels are housing cost burdened, versus 28 percent of urban households.” (The definition of “cost burdened” is when rent or home-ownership payments exceed 30% of income.)

The housing stock in rural counties tends to be older. In the Fifth District, 48% of units in rural areas were constructed prior to 1980 versus 44% in urban areas. In particular, the article notes, Virginia and West Virginia have a larger share of housing units constructed prior to 1950 in rural areas compared to urban areas. Because rural incomes are lower than in metropolitan areas, residents of aging properties are especially at risk of living in homes that have fallen into disrepair, the article notes.

One might think that the ready availability of inexpensive land, the receptivity to manufactured housing, and muted NIMBY tendencies might make it easier for people to build housing that is geared to lower rural incomes. If there are regulatory barriers to such development, the article does not discuss them.

But the article does highlight public strategies that might prove helpful. One mechanism is to create community land trusts (CLTs): nonprofit, community-based organizations that purchase and retain ownership of the land on which housing is built. One example is found in Virginia.

Land Trust (PCLT) is a Fifth District CLT that serves Charlottesville, Va., and the surrounding rural counties. PCLT creates homeownership opportunities for households earning 80 percent AMI or less by purchasing land and holding it in trust while the homeowner purchases the home on the land. The homeowner and PCLT enter into a 90-year ground lease on the land, which renews automatically. Removing the cost of land from the purchase price reduces monthly payments for the homeowner by anywhere from 20 percent to 40 percent. PCLT works in partnership with a community development financial institution that administers down payment assistance to eligible homebuyers.

Another strategy is creating land banks to acquire underutilized or vacant properties and prepare them for resale or lease. Acquiring the land can be tricky, requiring time and resources to deal with issues such as reluctant sellers, multiple owners in the case of inherited properties, tax foreclosure law, and titling defects. The article cites an example in Roanoke that could provide a model.

Roanoke, Va., established a land bank in 2019 with the goal of converting abandoned and derelict properties into affordable housing. After properties have gone through the tax delinquency process, the city will turn them over to a partner organization, Total Action for Progress (TAP). TAP will then work with other nonprofits, such as Habitat for Humanity, to renovate or construct new affordable housing on the site.

Most policy solutions are designed to help low-income households, which is a perfectly valid goal. But rural communities should not neglect middle-class housing. Local shortages of properties suitable for middle-class households make it harder to attract and retain workers, making the job of economic development all the more difficult.

Given the availability of land and the cultural acceptance of manufactured housing, the challenge of rural housing affordability should not be as intractable as it is in Virginia’s major metros. Kudos to the Richmond Fed for bringing attention to a long-neglected problem.