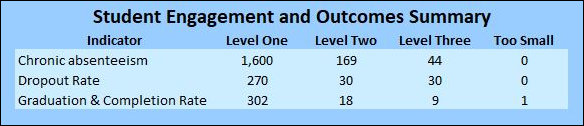

This table shows the number of schools falling into each accreditation category. Data source: Virginia Department of Education. Note: Dropout rate and Graduation & Completion rate apply to high schools only.

Under the new public school accreditation standards, the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) has begun tracking chronic absenteeism, the dropout rate, and the graduation & completion rate. The merits of these seemingly common-sense metrics is that (1) they are easy to collect, and (2) they measure very important things. In an ideal world, we’d like to see everyone graduate from high school, so we’d like to see the dropout rate go down and the graduation & completion rate go up.

The table above, taken from a VDOE press release issued today, shows the number of schools meeting accreditation standards for the three metrics (Level One), those that are near meeting the standards (Level Two), and those that fall short (Level Three).

While seemingly objective, these three metrics are very different from academic-performance metrics based on Standards of Learning (SOL) tests, which have gone through a rigorous design and approval process, and the testing of which is essentially audited and policed by VDOE to prevent cheating. While far from perfect — the criticisms of SOLs are many — the SOL numbers are reasonably trustworthy as indicators of students’ basic proficiency in reading, math, and science.

The student-engagement metrics are far easier for school administrators to manipulate. As I have noted previously, the pressure is intense for school districts, and individual schools within those districts, to show improving numbers. But administrators are dealing with the intractable reality of social breakdown, the dysfunctional culture of poverty, and blowback from schools’ own social promotion policies. The fact is, large numbers of high school students are unwilling to attend school or take classroom instruction seriously.

In the brave new world of Virginia education policy, school districts devote resources to rounding up truants and bringing them to school — all with the goal of reducing chronic absenteeism numbers. But dragging a kid to school doesn’t mean he (or she) will attend, much less participate in, every class — especially if they are so far behind that they cannot follow the discussions or hope to complete the work. If their classmates are lucky, the problem kids will just sit in the back of the class, fiddle with their smart phones or otherwise tune out. If the classmates are unlucky, the problem kids will act out and disrupt the class. Under the court-enforced disciplinary regimes in many school districts, teachers can no longer eject problem students without first engaging with them, reasoning with them, and trying to coax them into behaving — all of which takes time away from classroom instruction.

The new accreditation push is for schools to demonstrate that students are showing “progress” even if they fail to meet SOL proficiency standards. In grades 3 through 8, in which students take SOL tests every year, it is possible to show that a student, though still falling short of state standards, falls short by a smaller margin than the year before — thus showing “progress.” By contrast, I don’t know how it’s possible to objectively demonstrate progress in high school. If high schools rely upon teacher evaluations, then the process is easy to corrupt by leaning on teachers to fudge their judgments.

Given the contradictions and perverse incentives within the system, this is what I predict will happen: At many schools, we will see improving statistics for “student engagement” even as educational quality declines. More students will complete high school but the perceived value of a high school diploma (or certification of completion) will decline in the marketplace as employers confront the reality that increasing numbers of students are graduating high school without achieving mastery of basic skills. Those who are, in effect, socially promoted out of high school will be deceived to think they have skills that they do not. And those who worked hard to acquire those skills will see their diplomas devalued.

I’m not sure how we measure the declining value of high school diplomas, so it may be a long time before perception catches up with reality. But I fear a lot of damage will be done in the interim.