by James A. Bacon

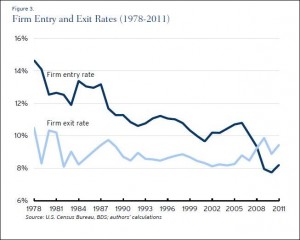

If you want to understand the intertwined phenomena of lackluster economic growth, persistent unemployment, stagnant wages and the income gap, I present to you the Rosetta Stone, a graph that explains all. It comes from a new paper written by Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan and published by the Brookings Institution: “The Other Aging of America: The Increasing Dominance of Older Firms.” The graph charts the long-term decline in entrepreneurship, as measured by firm formation, in the American economy. Firm formation traditionally has been one of the great strengths of the American economy but as can be seen above, the spread between firm creation and firm death has been narrowing since 1978 when the data series originated. Then in the mid-2000s, the two lines crossed. In the Great Recession and its aftermath, more firms expired than were born.

A decline in business formation is directly responsible for the weakness of the job market. The weakness of the job market is directly responsible for wage stagnation. And wage stagnation, which affects the 99% who depend upon wages/salaries for the livelihood far more than it does the 1% whose income comes from returns on capital, is directly responsible for the increasing income gap.

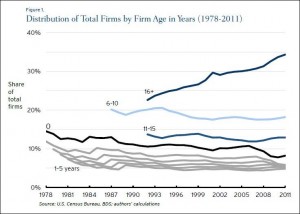

What accounts for the decline in entrepreneurship? Hathaway and Litan present data to help understand that question: Older, established companies are becoming more dominant in the economy. That trend can be seen at right. Write the authors:

There is a secular increase in the share of firms aged 16 or more years, while simultaneously there have been steady declines in the share of firms at every other age category during the history of our data,” the authors write. … Perhaps more surprising is the sheer pervasiveness of this trend, which is occurring in every U.S. state and nearly every metropolitan area, across all firm size categories and broad industrial segments; even in high-tech.

This trend, the authors argue, is a worrisome thing. “An economy that is saturated with older firms is one that is likely to be less flexible, and potentially less productive and less innovative than an economy with a higher percentage of new and young firms.”

In searching for explanations for this trend, Hathaway and Litan explore the possibility that technology-related economies of scale are driving a consolidation. Could the rise of Walmart and other superstores, for instance, account for the demise of mom-and-pop retailers, and could that that trend apply to all industries? Just the opposite, they find: “While economy activity is shifting into mature firms generally, it is the smaller firms where the most growth is occurring.”

The authors are at a loss to explain the trend, which is long-term in nature, transcending business booms and busts. Let me advance a hypothesis. There is a direct correlation between the size and scope of government and the rate of entrepreneurship. The greater the share of national resources controlled, regulated or otherwise captured by government, the lower the rate of new business formation.

In my book “Boomergeddon,” published in 2010, I suggested that the long-term growth prospects for the United States were poor, citing a number of reasons, including greater resource scarcity, loss of fiscal flexibility due to the massive size of the national debt, and the rise of the rent-seeker economy, the phenomenon in which corporations utilize the coercive power of the state to advance their narrow economic interests at the expense of the public good. As I wrote then:

It is an iron rule of political economy: Dominant industries will utilize their wealth and power to influence the political and regulatory arenas to protect their dominance. They will manipulate the regulatory process to favor themselves over smaller, nimbler competitors. They will see subsidies under the guise of saving jobs or advancing the public interest. They will raise tariffs and other trade barriers to limit competition from overseas. Corporations that maximize profits through rent-seeking are less likely to invest in productivity and innovation, the only true sources of economic progress. By gaining preferential access to capital, they will starve the entrepreneurial sector of the economy — as is occurring in the current business cycle. Rent-seeking companies will be more stable, but they will be less dynamic, economic growth will be slower, the tax base will be smaller, and deficits will be bigger.

The influence of the federal government over the economy has increased without let-up since the mid-1960s. There was a brief roll-back in the early 1980s, coinciding with the Carter-era transportation deregulation and Reagan small-government revolution and with a momentary resurgence in business creation. Then, as the federal government piled layer upon layer of regulation on the economy, the rate of business formation continued to falter, culminating with the Great Recession (not president Obama’s fault) and the imposition of an unprecedented regulatory burden (very much his fault). State and local government power has followed a parallel path in the arena of zoning and land use.

I’m not saying that all regulations are bad. Broadly speaking, environmental regulation is desirable and necessary (although subject to overkill in specific instances). But most regulatory initiatives have imposed huge costs on the economy overall, not only in complying with administrative requirements but in the rent-seeking it inspires. The longer and better established a firm becomes, the less likely it is to be concerned about survival and the more more time and resources it can devote to winning subsidies, tweaking regulations and creating barriers to new firms seeking to enter its industry.