by James A. Bacon

Solar energy is the cheapest source of energy available to the world today. The more solar energy we can generate, the better… up to a certain point. Once solar and other intermittent energy sources comprise 30% or so of the juice supplied to the electric grid, they create problems with reliability during extreme weather events, which can be surmounted only through investment in backup generation and energy storage. Until we reach that point, however, here in Virginia we should be doing everything possible to promote solar.

The Virginia Clean Energy Act (VCEA) has set the goal of achieving a 100% zero-carbon electric grid by 2050 (most of it supplied by solar and wind), but we’re nowhere near 30% renewables. Bacon’s Rebellion has highlighted one of the big obstacles facing solar developers in Virginia — getting large, utility-scale solar farms local permits in counties where residents want to conserve pristine viewsheds and traditional agricultural lifestyles.

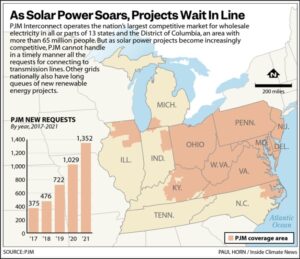

It turns out that there’s another obstacle — getting projects approved by PJM Interconnection, LLC, which oversees the electric grid in the 13-state region of which Virginia is a part. There is no lack of proposed solar projects — whether they are economically viable is a different question — and PJM is overwhelmed.

Once solar developers obtain state and local environmental and planning permits, they submit their projects to PJM for evaluation. PJM requires developers to absorb the cost of connecting their projects to the electric transmission grid. Costs vary widely depending upon the project’s distance from the grid and the grid’s ability to absorb additional capacity at the point of connection. Ascertaining that cost requires detailed engineering study. PJM does not have sufficient staff to keep pace with the surge in the number of projects, and approvals are taking longer than ever.

Developers of well-capitalized, utility-scale projects are frustrated because PJM has worked on a first-come, first-serve basis, and the project queue is clogged with small, unfinanced projects that may never be built. Indeed, between 2000 and 2015, only 24% of projects seeking connection nationally were completed — and the percentage is declining.

To work down the two-year backlog, PJM is changing its procedures. It is prioritizing projects that have financing and other attributes that maximize the likelihood that they actually will move forward if approved.

As reported by the Wall Street Journal this morning, The stakeholder-governed organization also is hiring more staff, budgeting funds for automation tools to streamline the approval process, and prioritizing 1,200 projects. Hundreds of other projects, mostly smaller ones, will have to wait.

What it means for Virginia. AgriSunPower LLC, a Richmond-based affiliate of national solar developer Hecate Energy LLC, is one of the developers whose projects will be reviewed by PJM. AgriSun’s most visible project is a $400 million, 280-megawatt solar farm in Pulaski County.

AgriSun CEO Felix Garcia has met with scores of local government officials across Virginia trying to develop other solar-farm projects. Many local officials ask him why the smaller projects they approved already aren’t getting built. The reason for most, says Garcia, is that they can’t get financing. Meanwhile, they’re clogging the PJM project queue, slowing the progress of larger, financially viable projects — like his — from getting built.

The Code of Virginia already requires projects to get bid bonds to ensure that developers fulfill their stated obligations. Garcia recommends that localities consider adding a financial vetting criteria to weed out the 75% of projects that have no financing and are gumming up the PJM project pipeline.

Hope springs eternal, however, and small project developers may hope that PJM approval will get them across the financial finish line. No doubt there would be a hue and cry against any proposal that would be perceived as stacking the deck against the little guy in favor of big out-of-state solar developers.

Virginia regulators need to decide how serious they are about meeting the VCEA 100% zero-carbon energy goals (or even the 30% renewable energy goal that I advocate). That means figuring out how far along Virginia is in meeting its goals. How many solar projects have received local approval? How many of those have received PJM approval? How many projects have been withdrawn? How many are languishing in the PJM queue? If Virginia projects can’t get connected, does that mean Virginia power companies end up importing more electricity from outside the state, and, if so, will the interstate transmission capacity exist to meet the load?

If we don’t know the answers to those questions, policy makers are stumbling around in the dark.