by James A. Bacon

The City of Norfolk is gearing up to take full advantage of tax breaks contained in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. City Council has designated the St. Paul area, home to three 50s-era housing projects, as an “opportunity zone.” Plans call for demolishing the three projects and replacing them with mixed-income development. The city will receive $30 million in Housing and Urban Development funds to jump-start redevelopment, but the bulk of investment is expected to come from the private sector.

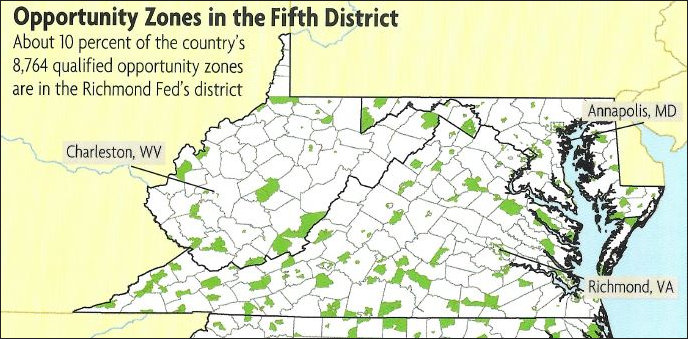

More than 8,700 such opportunity zones have been designated across the country; about 10% are located within the 5th Federal Reserve Bank district, which includes Virginia. Through a mix of incentives, investors in opportunity zones can defer, reduce or in some cases eliminate capital gains taxes in the zones.

While the tax breaks may prove effective at channeling investment capital into the designated zones, it is an open question if it will actually help the poor people living there, writes Jessie Romero in the current issue of Fed Focus, a publication of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The size of the potential tax break is what could lure new investment, but it depends on how profitable the investment is — which depends in part on rising property values and rents. So some observers fear that in many places, the opportunity zone designation will create or hasten a process of gentrification to the detriment of lower-income residents who don’t own their homes and instead are forced out by rising rents.

This strikes me as a legitimate concern. Indeed, the criticism goes to the heart of almost every government-subsidized redevelopment project. The more successful a project is commercially, the more likely it is to displace the very people it is meant to help.

The track record of tax-free investment zones — empowerment zones, enterprise zones, renewal communities, the New Market Tax Credit — is mixed at best. On the plus side, the tax incentives have steered capital into low-income neighborhoods, often creating job opportunities and higher wages. But rising rents and housing prices often displace the original residents. Moreover, some research suggests that empowerment zones simply shift economic activity from one place to another without any net gain.

This time will be different, advocates say. Opportunity Zones have several features to make them more effective than their predecessor programs. First, they are designated by state governors with input from local leaders who presumably know more about the needs and growth potential of their communities than federal bureaucrats. Second, the program pools resources of multiple individual and institutional investors, increasing the potential funds available and limiting the risk to any single investor. Third, the tax benefits are potentially larger.

Moreover, having learned from experience, governments can put “guardrails” into place — changes to zoning and permitting processes — to mitigate the effects of gentrification. That’s the theory. In practice, it’s not clear from the article what form such guardrails would take.

Bacon’s bottom line: I’m been skeptical of “urban renewal” projects for some time, but I’ve not been able to articulate precisely why. This article helps clarify my thinking.

Here’s the problem. Private-sector developers are driven by profit. They make profit by either renting or selling housing units for the highest price they can. Developers want to see property values rise. If property values don’t rise, and if developers don’t make profits, then they will stop investing. Duh! If property values do rise, then the lowest-income residents will be displaced… unless special measures (such as “workforce housing”) are put into place to guarantee them housing… which adds to redevelopment costs and cuts into profits. Cities can add “guardrails” but these add more layers of red tape and administrative delays… which cuts into profits.

Let me state the obvious: Lower-income people live in the most dismal neighborhoods because that’s all they can afford. People who can afford to move out of the worst neighborhoods do so as soon as they are able. If through a combination of HUD subsidies and tax breaks a locality improves the quality of a neighborhood, property values will rise. When property values rise, lower-income residents will be displaced.

The contradiction is inherent in urban redevelopment.

In the long run, society can’t improve the condition of poor people by upgrading the quality of their neighborhoods. Society can improve their condition by increasing the supply of housing stock generally, and encouraging smaller and/or affordable units such as trailers, manufactured housing, cargo-container housing, tiny homes, boarding houses, and single-room-occupancy housing. Society also can improve the lives of poor people by helping them, through education and workforce training, to become more economically productive and, thus, to increase their earning power.

No matter how well intentioned, urban renewal projects are a dead end. Indeed, by consuming resources that could be better applied elsewhere, they arguably represent a net economic loss to society.