Last week Victoria Manning, a member of the Virginia Beach school board, posted a comment on her Facebook page noting that the school system had added 300 additional English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL) students the past year, mostly from “South America.” The city’s ESL budget had increased more than $1 million over two years, she wrote. “Continuing to educate South Americans is not sustainable.”

Predictably, her comment drew fire. “When you say and specifically mention Latin Americans, you’re telling me indirectly that you have something against people that are brown or Black or Indian or aboriginal and so on that come from south of the United States border,” said Luis Rivera with the Virginia Beach Human Rights Commission. The Virginia Beach Democratic Committee termed the statement “racist.”

Once you call someone a racist, you pretty well shut down the conversation. But there are legitimate issues here. That the ESL program is causing fiscal stress to Virginia Beach schools is undeniable. WAVY-TV reports the numbers here.

Manning elaborated upon her comments to the television station. The city is already short 100 teachers, she said, and now it has to add eight more ESL positions. “If you have a program with an increasing number of students with fewer teachers then the program is unsustainable.”

Given the flood of immigrants crossing the border in the past year — the New York Times reports that the 1.7 million illegal migrant encounters was the highest since 1960 — it is not unreasonable to assume that many of the additional ESL students in Virginia public schools entered the country illegally. Likewise, it is fair to say that Virginia Beach is paying a price for lax U.S. border policy.

While describing the situation as “unsustainable,” Manning did not say what the school system should do about it. She did not say that the added positions should be denied funding, nor did she dispute that Virginia Beach has an obligation to educate all children, even if they are here illegally. Such a conclusion can be inferred from her remarks, but she did not say so explicitly, and the comment can be interpreted just as plausibly as an expression of frustration. Perhaps she will clarify.

Virginia Beach is not alone in dealing with the fallout from illegal immigration. According to Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) statistics, the number of Hispanic ESL students statewide taking the math Standards of Learning exam increased from 38,000 in the 2010/11 school year to 47,500 in 2020/21 — a 25% increase over the decade. However, VDOE distinguishes between “former” and current English Learners. If former ESLs are excluded on the grounds that they now can speak English, the number of ESL students is lower, increasing from 28,900 to 31,500 over the same period, or 9%.

The VDOE numbers point out trends that are both encouraging and alarming.

The good news is that the number of former Hispanic ESL students appear to be increasing far more rapidly than that for current ESLs. VDOE does not provide an official breakdown of “former” ESL students and current ESLs but the number can be calculated. By my reckoning, the number of former Hispanic ESLs was 9,000 statewide in 2010/11 and 16,000 in 2020/21 — a 77% increase, far outpacing the percentage increase for current Hispanic ESLs. The implication is that large numbers of Hispanic students are moving out of the ESL programs into mainstream classes.

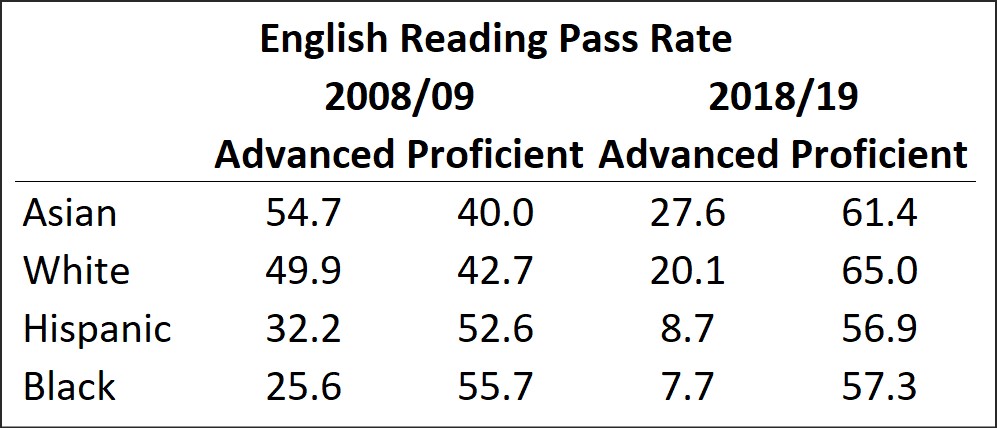

The bad news is that Hispanic students are under-performing Asians and Whites, as measured by SOL pass rates, by a wider margin in 2018/19 (the last year of pre-COVID SOL tests) than they were in 2008/09. (All racial/ethnic groups showed declines over the 10-year period because the scoring standards got tougher. But Hispanics showed a greater decline than Asians and Whites.)

Continued academic under-performance should not obscure the fact that Hispanic immigrants have shown considerable progress in overcoming the language obstacles that hold them back.

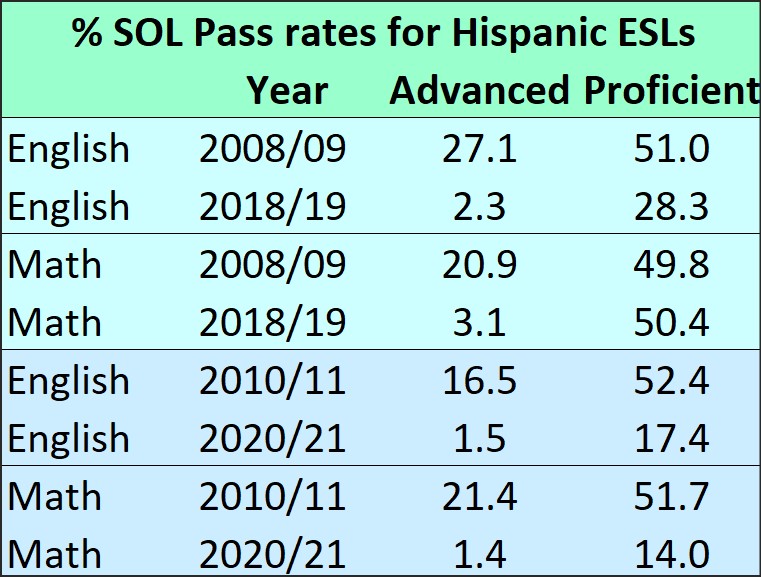

Whether Hispanic immigrants will continue to demonstrate upward academic mobility is an open question. SOL pass rates for Hispanic students enrolled in ESL programs has plummeted in both English reading and math. The collapse was catastrophic in the COVID-afflicted 2020/21 school year — only 15.4% passed (proficient plus advanced) in math, and only 18.9% in English reading, down from pass rates in the 60s and 70s a decade previously.

To factor out the COVID effect, I compared the last pre-COVID year, 2018/19, with ten years previously. The total pass rate (advanced plus proficient) went from 78.1% in English reading to 68.9% over the 10-year period, and from 70.7% for math to 53.5%, roughly consistent with the experience of other groups in response to the tougher pass standards.

Bacon’s bottom line: The flood of illegal immigrants, including Hispanics, has a fiscal impact on Virginia taxpayers as the newcomers settle in our communities and enroll in our public schools. I strongly believe that we need to strengthen our border policies. But we also have to deal with the fact that the illegals, once here, are not likely to be deported. We then face a choice: Do we educate the children in the hopes that they learn the language, assimilate and become productive members of society, or do we let them languish?

That decision, I think is made easier by the fact that so many children of illegal immigrants do learn English and do graduate from ESL programs. I’m not going to flagellate myself and curse America as a racist society because Hispanics as a racial/ethnic group lag Whites and Asians in academic achievement. It is not a sign of “white supremacy” that our public schools are being flooded with children (Hispanic or otherwise) who don’t speak English and have a lot of catching up to do. But they’re here, and we have a moral and practical responsibility to educate them properly so they can join the American mainstream.