Hampton Roads base flood – 1% annual risk

by James C. Sherlock

We have work to do, and need to do it quickly and well.

- If we want to get storm defenses built before major storm damage rather than after; and

- if we want the federal government to pay 65% of the costs.

Let’s assume we do.

The “Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Planning Framework” appears to be heading in a direction that may miss important pieces of any benefit/cost assessment. And those assessments drive federal interest.

The assumption in Framework going forward appears to be that the value of flood protection is in loss avoidance. Exclusively.

Indeed, all of the work that I can find in flooding assessments Virginia is put towards the goal of understanding the costs of such losses.

Not sufficient, but fixable.

Loss avoidance calculations are insufficient

ODU’s An Analysis of the potential costs and consequences of a hurricane impacting the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News metro area is an example. It is excellent, but it is exactly what the title suggests.

The ODU analysis assesses the costs of loss based on FEMA’s HAZUS model. HAZUS, the official U.S. loss assessment model, is not mentioned in Framework.

That appears to be because HAZUS is, as far as I can determine, not used at the state level in Virginia. I had expected HAZUS, a FEMA model, to be used by the Virginia Department of Emergency Management. That office tells me it is not. There is no reference to it anywhere in the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCI), now the lead office for flood mitigation planning in Virginia.

But let’s get past that and guess that the City of Norfolk, which uses HAZUS, ODU and other municipalities and academic institutions will introduce the state to it.

The calculation of potential losses tells only part of the picture.

We need two other elements of measurable benefit — non-disaster government transfers avoided and the state tax revenue increases that result from the government spending.

Non-disaster government transfers

The first is the costs of non-disaster government transfers. A paper,

“The Fiscal Cost of Hurricanes: Disaster Aid versus Social Insurance,” published in the American Economic Journal American Economic Journal: Economic Policy in 2017: 9(3): 168–198

“shows that US hurricanes lead to substantial increases in non-disaster government transfers, such as unemployment insurance and public medical payments, in affected counties in the decade after a hurricane. The present value of this increase significantly exceeds that of direct disaster aid. This implies, among other things, that the fiscal costs of natural disasters have been significantly underestimated and that victims in developed countries are better insured against them than previously thought.”

HAZUS models the disaster aid channels, but not the non-disaster government transfers.

Since unemployment insurance and Medicaid among others are state costs, the modeling for Virginia will need to include costs that, when avoided, turn into savings if the defenses are built before the flood.

Flood mitigation investments and the velocity of money

We also need to understand the economic benefits of the investments themselves.

We have detailed information on the net economic effects in Louisiana in general and New Orleans in particular of flood control spending after Katrina. We should use it.

The benefits of those increased state tax receipts are additive to the losses avoided in the benefits/cost equation that determines the economic value of any project.

The basic economic concept of the velocity of money explains why Louisiana tax receipts soared to a level no one predicted. The velocity of money is the rate at which people spend cash.

The Federal Reserve calculates that figure to measure the effects of the money in circulation of economic output. High velocity is a feature of a thriving economy. Low velocity means an increased amount of the available cash is used for savings and investment.

Construction spending is by its nature high velocity money.

The contractors have to pay their people, buy and rent equipment, purchase materials, rent barges to support waterborne construction, pay for fuel, etc. The materials and equipment vendors pay their people, buy more materials, etc. The assessed valuations of buildings newly protected by flood control measures rise. All generate tax receipts.

The money flows also into small businesses not directly in the contracting chain such as motels, grocery stores, restaurants, gas stations, etc. That money flow is significant and generates yet more tax revenue.

There have been several books written about the velocity of money and the subsequent tax windfall for Louisiana attributed to the federal spending.

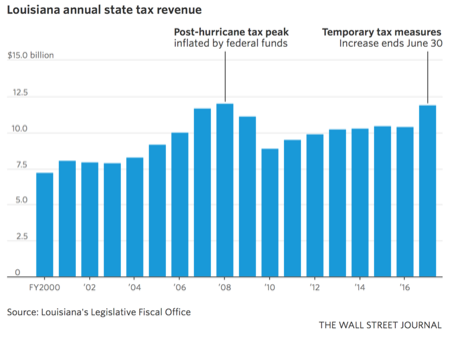

To cut to the chase, look at what happened to Louisiana annual tax receipts from federal spending after Katrina. Roughly 40% of that federal spending was in the funding of the New Orleans’ Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS).

Louisiana annual tax receipts 2000 – 2017

Louisiana tax receipts soared far above pre-Katrina levels.

That happened in the face of massive job losses and more than 100,000 people leaving the state. After the embarrassment of riches in 2008, the legislature passed a tax cut. It turned out to be too big of a cut, and some taxes needed to be restored.

Note also that the Great Recession in 2008-09 and a collapse in price of WTI spot crude during that recession, usually a big factor in Louisiana tax receipts, still did not return tax receipts to below pre-Katrina levels.

So we clearly need to assess the effects of the economic investments themselves from an HSDRRS-like project in Hampton Roads. We need to know the effects of those investments both before such a hurricane and after one.

The economists at ODU who produce the economic assessments of Hampton Roads GDP annually should be able to figure that out closely enough for government work.

Louisiana’s Legislative Fiscal Office knows where every dime of tax receipts came from in each year. They will share. Just a thought.

Going it alone – the example of Virginia Beach

Virginia Beach has a $567 million bond proposal on this year’s ballot to fund local flood mitigation projects. That is a lot of debt, even for this city.

The money will target high rainfall flooding and some sea level rise but not specifically storm surge, particularly at the Chesapeake end of the Lynnhaven River basin, our city’s biggest storm surge vulnerability.

It doesn’t include any regional efforts. And it does not anticipate any federal funding. Property taxes on homes and businesses will go up to pay the debt.

But I am going to vote for it. The work needs to be done. I hope it passes.

Bottom line

So, the state needs to do some things that the Framework suggests are not on its agenda:

- fund the economic analysis of non-disaster government transfers and the tax value of the investments at current tax rates. Those assessments are not reflected in the federal HAZUS model; and

- as discussed in an earlier piece, recognize the primacy of the federal government in the process and stand up as the nonfederal sponsor of flood control projects.

And did I mention building the protections before a hurricane? In the direction and pace that DCI is going, we will never build anything that a local government doesn’t pay for.

Thus the Virginia Beach bond proposal.

I’ll discuss the regional planning constructs that the Framework depends on in a follow-on post. There is no good news historically to suggest that the regional commissions can deal with regional flood control.

Too big a bill. Too many different municipal agendas and abilities to pay. That is a big reason Virginia Beach is going it alone.

One more mentionable — the federal government pays 65% for USACE civil works projects approved through Congress. USACE has a small discretionary budget, but it won’t get us where we are going.

The Commonwealth needs to get across the Congressional finish line, not the least because not every city and county can pay the kind of bill that Virginia Beach plans to pay.

And they should not in many cases. Storm surge doesn’t respect political boundaries.

The state needs to change direction to get where it wants to go. Hope it does.