Amazon will donate $3 million to support affordable housing in Arlington County, the company has announced. While government officials and charities welcomed the donation, reports the Washington Post, critics contend that the sum is sufficient to build only a handful of units.

According to the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance, new housing in the Virginia suburbs costs about $350,000 per unit. In other words, Amazon’s gift is enough to build about 8.6 housing units. For purposes of comparison, the tech giant expects to employ 25,000 at its Arlington facility, and that doesn’t include jobs created by vendors, partners, spin-offs and support entities such as Virginia Tech’s new technology campus that locate near Amazon’s HQ2.

In other words, the donation is meaningless. The number we should focus on, however, is $350,000. If that’s what it costs to build “affordable” housing in Northern Virginia, then no wonder there is a housing panic.

The cost per square foot of manufactured housing in the United States, including delivery and installation, ranges from $100 to $200 per square foot. If we assume 1,000 square feet per affordable housing unit on average, then we’re talking in the range of $100,000 to $200,000 as a benchmark for building a housing unit. (Actually, housing built for lower-income households would require less customization, so a realistic figure would be on the low side of that range.)

The implication is that the cost of acquiring and developing the land for affordable housing is $200,000 to $250,000 per unit. That is the problem that no one seems to be addressing.

Arlington County is perhaps the most densely zoned locality in Virginia, but it’s not zoned densely enough. Arlington sits at the center of the Washington metropolitan area, one of the largest and wealthiest metros in the country. Land should be developed at high densities. The same can be said of neighboring Alexandria, Falls Church and eastern Fairfax County.

In a free market for housing, developers would acquire under-utilized land — old car dealerships, decaying strip malls, long-in-the-tooth residential subdivisions — and recycle it at much higher densities, spreading the land development costs over a greater number of units. Due to an array of zoning restrictions, however, that’s not possible.

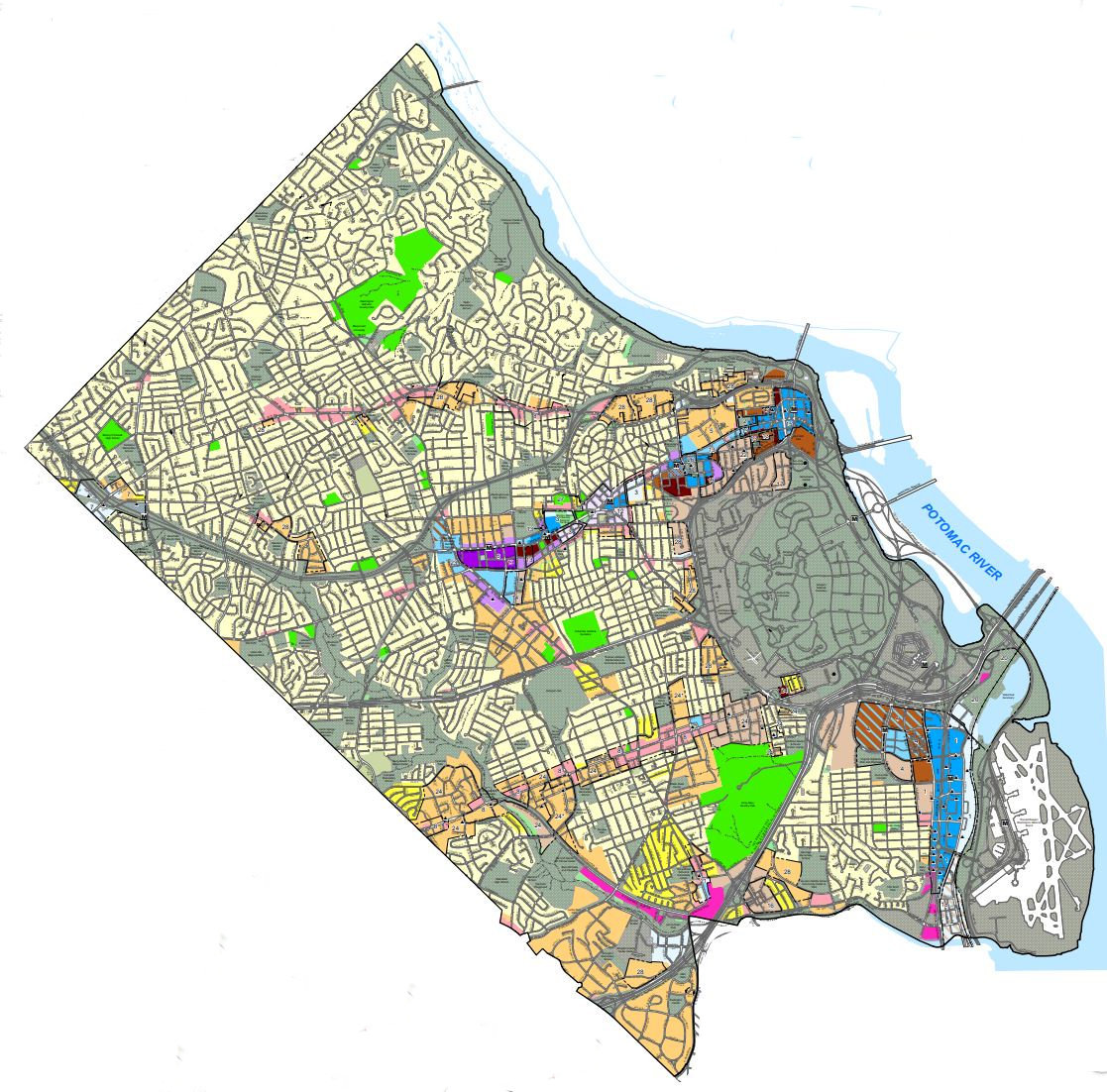

Here’s a current map of Arlington’s zoning code. Land restricted to low-density single-family dwellings (one to ten units per acre) is marked in pale yellow — more than half the county. Excluding Reagan National Airport and Arlington Cemetery, two-thirds of developable land is restricted to low density. Again, “low density” is a relative term. Arlington’s low-density zoning is higher density than much of, say, Richmond or Norfolk. But in the context of its position at the center of a major metropolitan area, it is artificially low density.

Here’s a current map of Arlington’s zoning code. Land restricted to low-density single-family dwellings (one to ten units per acre) is marked in pale yellow — more than half the county. Excluding Reagan National Airport and Arlington Cemetery, two-thirds of developable land is restricted to low density. Again, “low density” is a relative term. Arlington’s low-density zoning is higher density than much of, say, Richmond or Norfolk. But in the context of its position at the center of a major metropolitan area, it is artificially low density.

(It’s not fair to place the entire onus on Arlington. The Washington metro housing market is regional in scope, not restricted to a single county. In any affordable-housing analysis, one also needs to consider the comprehensive plans for Alexandria, Falls Church and Fairfax County as well.)

The cost of land per unit of housing is expensive (1) because land use is highly restricted, and (2) local government imposes regulatory costs such as environmental fees, proffers, and utility hookup fees. If there is any hope to address the affordable housing crisis in Northern Virginia, Arlington and its neighbors need to reduce these restrictions, fees, and costs. Coughing up $35 million in taxpayer funds to address affordable housing — a significant sum even for Arlington — is a drop in the bucket, enough to build 100 new affordable dwellings. It is literally impossible to address the affordability issue without sweeping zoning changes.

How about transportation? The feedback I’ve gotten on this blog is that increasing the density of housing will overwhelm local transportation systems. Not necessarily.

The lower-income households who would avail themselves of new affordable housing units are significantly less likely to own automobiles and more likely than the general populace to use public transportation. As it happens, Arlington has a superlative system of local and regional public transportation. Indeed, an increase in population density along Metro rail and bus lines would generate larger ridership at little additional marginal cost, thus improving the economics of the region’s shaky mass transit system.

I’m not saying that greater density would have zero negative impact on Arlington’s streets and roads, but I am saying that the impact would be significantly mitigated by the county’s and region’s large investment in mass transit.

There are no easy, painless solutions in urban development, just complex trade-offs. But some trade-offs are better than others. Higher density for affordable housing in an area well served by mass transit is one of them.