Car in tree in Nelson County after Camille

by James C. Sherlock

I offer this survey of Virginia’s biggest interior floods since 1969, mostly courtesy of the National Weather Service, as equal time for my reporting on coastal flooding in Virginia.

The interior is where the most deaths have occurred in Virginia floods, not the coast.

The deaths reach those levels in interior Virginia through a combination of:

- topography, especially where rain runs off the mountains,

- sometimes relatively short notice alerts compared to coastal weather forecasting, and

- the historic practice of building in hollars in the mountains and bottom lands adjacent to rivers.

Rainwater surging down mountains into rivers can be catastrophic at every point in its flow.

This will provide both a photo remembrance and a brief written record of each of those four storms.

Hurricane Camille August 19-20, 1969

The biggest natural disaster in Virginia history measured by deaths occurred in Nelson County in 1969. It resulted from flooding from the remnants of Hurricane Camille.

A special session of the General Assembly was required to declare over 150 people dead because the mudslides buried them so deep (see image) that the bodies would never be found.

Aerial shot of massive mudflows in the mountains of Nelson County, VA, created by Hurricane Camille’s remnants, Dick Whitehead Collection

It literally cleared a path for Wintergreen. That land was sold to the developers in 1972.

From the National Weather Service https://www.weather.gov/safety/flood-states-va

“Two days after making landfall, Camille had been downgraded to a tropical depression and turned east from the Ohio Valley into the Central Appalachians. During the evening of the 19th, Tropical Depression Camille began to interact with a very humid late summer air mass over central and western Virginia along with a stalled east to west oriented frontal boundary. This combination of factors, along with the higher terrain in the Blue Ridge Mountains, produced continuous thunderstorms from late in evening on the 19th through the morning hours on the 20th. The heaviest rain fell across Rockbridge, Amherst and Nelson counties, where rainfall totals of 10 to 30 inches were reported.”

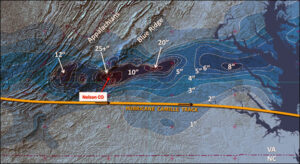

Rain swath created during Camille’s transit across the Mid Atlantic; rain contours in inches: Tom Rabenhorst, UMBC, adapted from F. Schwartz, 1970, Monthly Weather Review

“As a result of this rain, rivers and streams exploded with rapid water rises. Top soil in the higher terrain gave way, leading to massive mudslides, taking a large numbers of large trees. The trees and mud served to create temporary dams, which, when they broke, led to massive walls of water moving downstream with rapid water level rises that trapped people in their homes, destroyed buildings and bridges and often separated family and friends.”

“When the rain ended during the morning hours of the 20th, the state had whole towns under water or swept away.

In Nelson County alone, the death toll was 123. As the flood waters moved into the James River, from the Tye and Rockfish rivers, the water level rises pushed the James River into the major flood category. All gaging stations east of Holcomb Rock near Lynchburg recorded either the 2nd or 3rd highest water level in recorded history. In Richmond, the James crested at height of 28.60 ft., which was surpassed only during Hurricane Agnes (1972) and the Election Day floods in 1985. At Palmyra, on the Rivanna River, the river reached a record height of 39.85 ft. (flood stage 17 ft.), and at Buena Vista, the Maury River reached a record height of 31.23 ft. (flood stage 17 ft.).

As a result of the damage and flooding, all communication between Richmond, the capital of Virginia, and the Shenandoah Valley was cut off, slowing any assistance.

Overall, 153 deaths were attributed to the flooding from Camille with damage estimated between $113–$140 million dollars in 1969 dollars (over $1 billion today).”

The Schuyler bridge and hydroelectric dam on the Rockfish River were washed out by the hurricane forces. The bridge and power house have washed down river, but the smoke stack remains in place. Located at the intersection of Rt. 617 and Rt. 693 in Nelson County. 8/25/1969. No. 69-2080, Virginia Governor’s Negative Collection, Library of Virginia

For some of the best historical reporting you will ever read, see the Washington Post for the details of the tragedy of Camille in Virginia.

Hurricane Agnes, June 21-24, 1972

Agnes brought Virginia rainfall that included 16” in Chantilly, 13.65” at Dulles Airport and 11.4” in The Plains in Fauquier County.

The Potomac River peak stream flow measured in cubic feet per second (CFS) in the aftermath of Agnes set a record of 359,000 CFS. That’s compared to the January 1996 flooding flow of 347,000 CFS. To put that in perspective, the average stream flow for the month of January along the Potomac is only 13,000 CFS.”

Damage in Virginia was $222 million in 1972 dollars ($1.4 billion today).

The bridge over the Appomattox River on Rt. 15 near Farmville after Agnes.

Rt. 1 Bridge over the Occoquan River sways under the pressure of Agnes flood waters

Election Day Flood November 4-5, 1985 – Back-to-back systems spell disaster

“In Virginia, Election Day 1985 will not be remembered for who won which office or which political party made a statement, but for record flooding that occurred across much of central and southwestern Virginia. This event had a slow build up to the final dramatic conclusion on Election Day.

On October 31, Hurricane Juan made landfall along the Gulf Coast and slowly began a track to the north through Alabama, eventually weakening over the Smokey Mountains of Tennessee and western North Carolina.

Finally Juan was absorbed by a slow moving cold front. In advance of Juan, tropical moisture had pushed up through the Carolinas into Virginia, enhancing rainfall across the state on the 1st thru the 3rd of November. This produced 1 to 4 inches of rain across the state; however, the system that followed Juan provided the knockout punch.

By the morning of the 4th, a developing system over the central US plains was strengthening and caused the front to the east to stall over Appalachian Mountains, while a new low pressure area developed in the Gulf of Mexico. This situation allowed the tropical moisture to continue to feed into the region. As this low lifted northward through the Carolinas, the rain intensified with embedded thunderstorms. Rainfall amounts of 6 to 10 inches occurred on the 4th and 5th. Overall for the 6 day period rain amounts of 6 to 14 inches were common with a high of 19.70 inches reported in Montebello, VA in Nelson County.

With the soil already saturated by the rains from Juan, the rain immediately began to run off into area creeks and rivers. The rivers began to rise, quickly reaching bankfull and continuing to rise. The hardest hit areas were parts of the Roanoke River Basin and also the James River Basin. The city of Roanoke saw water levels rise nearly 19 feet in 12 hours, cresting at a record height of 23.35 feet.

These rapid water level rises left many people stranded. Many people had to be rescued with boats, helicopters, tow trucks, and virtually any vehicle that could make it through the flood waters.

The death toll from the flooding was 22 people in Virginia with the monetary damage estimated at near $800 million in 1985 ($2 billion today). The river flooding impacted four river basins with major flooding (Shenandoah, Roanoke, James and Chowan basins), with 23 points reaching or exceeding major flood stage and 5 points set all time record water levels.”

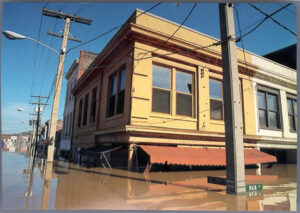

Corner of US 60 and N17 St in Shockoe Bottom, 1985, Richmond VA, courtesy VDEM

Roanoke Flooding – Election Day Flood 1985

Hurricane Fran September 5-8, 1996

“Although the rain began on the 5th, the center of Tropical Storm Fran moved into southern Virginia, near Danville, on the morning of the 6th and quickly raced north northwest across the Blue Ridge and into the Central Appalachians near Morgantown WV by the evening of the 6th.

Despite the rapid movement of the system, the rain was heavy and with the southeasterly flow that developed ahead of the center of Fran. The terrain helped to enhance that rainfall. Overall, along the track of the storm, the rainfall amounts were between 3 to 7 inches, with amounts of 7 to 15 inches across the Shenandoah Basin.

As a result of this rain, major flooding occurred from the Roanoke River basin northward through the James, Shenandoah and Potomac River basins, including 4 locations in the Shenandoah Basin which recorded all time record river levels.

The hardest hit areas were in Page and Rockingham counties. In Page County, The Virginia Department of Emergency Management reported hundreds of people were rescued with 78 homes destroyed and 417 damaged.

In the town of Luray, one home was pushed off its foundation by flood waters from Hawksbill Creek and deposited on the high school football field. Water level rose as high as 2 feet from the top of the field goal upright. In Rockingham County, 40 homes were destroyed and 105 suffered major damage.

Potomac River at Chain Bridge near Washington, D.C. Looking upstream during flood of September 8, 1996 and during low flow. Images from United States Geological Survey

The state incurred nearly $350 Million ($595 million today) in damage with a death toll of 6.”

Bottom line

This essay illustrates that flooding in Virginia is hardly just about the coasts. The Commonwealth will have to pay attention to flood damage mitigation in the interior.

That might include measures like:

- additional castles in cities along the major rivers;

- encourage people to resettle out of the hollars and bottomland to higher land;

- hardening of threatened major infrastructure with particular attention to water supplies, electric power plants and industrial storage of chemicals as a few examples; and

- attention to the resilience of bridges and dams.

For federal funding support, any project will need to pass the federal benefit/cost criteria for investment.

That economic model is, of course, owned, maintained and run for the federal government by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.