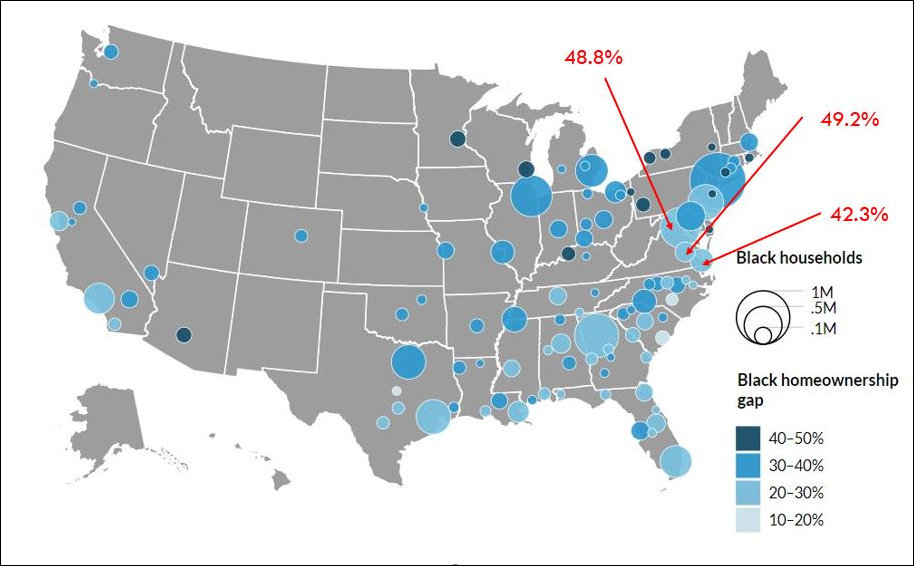

This map shows the white/black home ownership gap in U.S. cities with largest black populations. The lighter the circle, the smaller the gap. The percentages I have added in red show the black home ownership rate for Virginia’s three largest metros. Map source: Urban Institute

Numbers you’ll never see in Virginia’s SJW media: Virginia’s three largest metros — Washington, Hampton Roads and Richmond — have higher black home ownership rates and smaller white/black gaps in the rate of homeownership than most of the country. The map shown above comes from an Urban Institute study mapping the black home ownership gap.

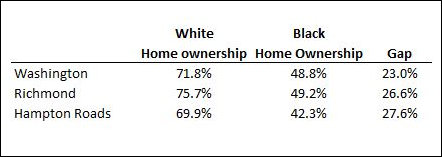

Here is the breakdown by Virginia’s major metropolitan areas:

The data came to my attention today thanks to a Washington Post article discussing “The ‘heartbreaking’ decrease in black home ownership” since 2003. A key thesis is that “racism and rollbacks in government policies are taking their toll.”

The article acknowledges that the reasons for the downturn in black home ownership are “varied and complex.” They include a lack of affordable housing in some areas, chronically low inventory in others, differences in wealth and income, and rising student debt…. and, of course, housing discrimination. Discrimination may or may not be a factor in mortgage lending today. That’s the go-to explanation for left-of-center policy analysts, whose analysis I don’t always trust.

Permit me to explore a dynamic that neither the Washington Post nor the Urban Institute really explored.

There’s no question that housing discrimination was pervasive in the past. Barriers against black home ownership began falling with Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s and have been continually chipped away since, culminating with efforts under the Clinton and (George W.) Bush administrations to actively encourage black home ownership (with disastrous consequences when the 2007 real estate bust drove millions of sub-prime borrowers into foreclosure). Over this same period, a countervailing force has emerged: Zoning codes and other municipal practices have restricted the supply of housing and loaded new regulatory costs (typically associated with environmental protection) onto home builders — costs they passed on to buyers. Thus, while blacks were legally free to buy houses anywhere, they entered housing markets at a time when price of home ownership was shooting higher. Zoning codes protected the housing values of incumbent home owners, disproportionately white, at the expense of non-homeowners.

Modern-day zoning codes weren’t designed to discriminate against blacks. But they impacted anyone, of whatever race or ethnicity, who wasn’t fortunate enough to own a house early in the decades-long housing-price boom and enjoy the scarcity-driven increase in values. This trend affects poor whites as well, and it helps explain why it has been so difficult in recent years for poor whites to relocate from rural areas with depressed economies to booming metros. But the problem disproportionately affects African-Americans.

If my analysis is correct, we’ll find a strong correlation between the restrictiveness of zoning policies in metropolitan areas, the unaffordability of housing, and the low rate of African-American home ownership. I have not conducted that analysis, but I’ll put it out there as a hypothesis. If I am correct, the problem stems not from conscious discrimination against blacks but from policies of local governments, acting for a wide variety of motives (including progressive environmental policies, NIMBYism, a distrust of developers, and a desire to control growth). Secondly, I will posit that there is a strong relationship between the political hue of a metropolitan area and its propensity to enact zoning and environmental restrictions. Activist governments, it goes without saying, are normally run by Democrats.

It’s an avenue worth researching. For some unfathomable reason, though, it does not seem to be one that progressive think tanks, academics, or newspaper reporters are motivated to pursue. If it doesn’t support The Racial Oppression Narrative, such conjectures hold no interest.

I acknowledge that my argument in this post is anecdotal. I don’t have time in the course of a couple of hours to conduct the kind of research that think tanks take weeks to complete. While my conclusions are provisional, the anecdotal evidence is powerful.

Richmond is not exactly a bastion of progressive attitudes towards race — its history of residential segregation is well documented — but with a 49.2% rate of black home ownership, it has one of the highest rates of black home ownership in the country. The only cities I could find on the Urban Institute’s interactive map (I might have overlooked someone) with higher rates: Charleston, S.C. (53.5%) and Florence, S.C. (52.1%).

Compare those numbers to progressive West Coast metros: San Francisco (31.2%), Los Angeles, (33.5%), Portland (30.9%), Seattle (28.%). And compare it to progressive Northeastern metros: New York (31.9%), Boston (36%), Providence (26.2%), Albany (26.0%). (With a 49.1% black home ownership rate, Philadelphia is an exception.)

The lowest white/black gap in home ownership: Fayetteville, N.C., (17.4%) and Charleston (18.1%).

As the Urban Institute concedes, the white/black gap in home ownership is greatest in the Northeast and Midwest and least in the South and West. That flies in the face of all our stereotypes about racial prejudice. According to The Narrative, discrimination is far worse in Trump-voting Ku Klux Klan states like South Carolina or in the Capital of the Confederacy than in centers of enlightened thinking such as New York and San Francisco. Yet somehow, blacks are more likely to own their own houses, and the white/black gap is least, where bigotry supposedly is the worst.

Maybe much of what we think is true just isn’t. And maybe the conventional remedies are just wrong.