by Carol J. Bova

In April, 2015, two Tennessee-based not-for-profit hospital organizations with a 75% market share in Southwest Virginia said a merger would allow them “to address the serious health issues affecting the region and to be among the best in the nation in terms of quality, affordability and patient satisfaction.” The merger would involve 21 hospitals in 21 counties in two states, and about 960,000 people.

The FTC opposed the merger. The commission said that courts and antitrust agencies view an increase of more than 200 points on a standard measure of market concentration — the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) — as likely to be anticompetitive. The new company’s post-merger score would increase 2,441 points.

In the hope that this merged company might solve overwhelming regional health disparities, Virginia and Tennessee ignored the FTC and took a leap of faith. Both states passed legislation to allow cooperative agreements for a merger of the two systems. To confer immunity from federal and state antitrust laws, the legislation provided for state regulation and active supervision to ensure that the benefits would outweigh any disadvantages.

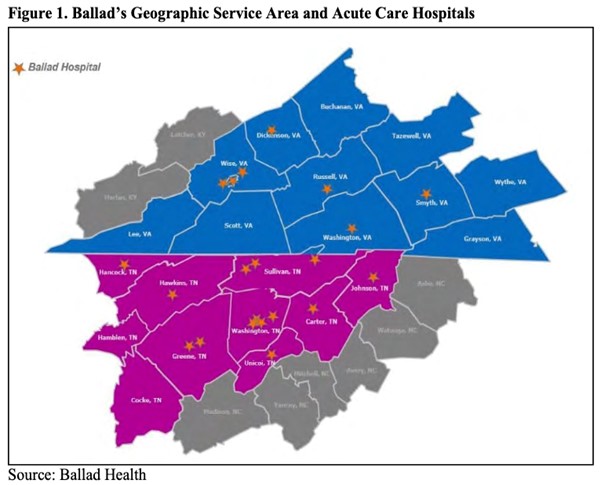

Five years have passed since Mountain States Health Alliance (MSHA) and Wellmont Health System merged their organizations and created Ballad Health, formalizing a monopoly health provider in Virginia’s far Southwest, including the counties of Buchanan, Dickenson, Lee, Russell, Scott, Smyth, Tazewell, Washington and Wise Counties, and Norton and Bristol cities.

A merger, serving a region the size of New Jersey, is a complex and challenging endeavor. How has the regulated monopoly worked out? In a five-part series, Bacon’s Rebellion will examine : (1) what was promised, (2) Ballad’s administrative and financial cost cuts, (3) the restructuring of Ballad’s Virginia operations, (4) changes in hospital quality measures, and (5) Ballad’s handling of the COVID-19 epidemic.

Our broad conclusions: Ballad did cut costs, and it did restructure operations. Hospital quality measures have improved somewhat, though not as much as promised due in part to the COVID-19 epidemic. Ballad struggled to deal with that epidemic, in large measure due to a shortage of doctors, nurses and medical practitioners that is widespread across much of America.

In February 2016, Wellmont Health System and Mountain States Health Alliance (MSHA) filed formal applications with the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) and the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) for approval to merge their organizations. Wellmont and MSHA had a total of 21 hospital facilities, numerous nonhospital sites, about 15,000 employees, and more than $2 billion in revenue.

The proposed merger was controversial.

In September, 2016, according to the Johnson City Press, “Representatives of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, Bureau of Economics, and Office of Policy Planning articulated their disapproval in a 123-page document submitted to the Southwest Virginia Health Authority and Virginia Department of Health.” The FTC staff said the market share of the two hospital chains would be 71.13% in the 21-county area, exceeding “those of past hospital mergers that the FTC and federal courts have found to be anticompetitive.” (Fitch Ratings in 2020 said Ballad Health has a “commanding 74% inpatient market share across a 21-county region in Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia…. No other competing health system has more than a 4% market share in Ballad’s primary service area.”)

The FTC’s independent assessor in November, 2016 concluded “that the benefits claimed by the parties are unlikely to be achieved and that any benefits of the merger that might actually accrue are not likely to be significantly better than what could be achieved by alternative means that did not reduce competition.”

Virginia hired its own expert, Robert Town, Ph.D., to report to Attorney General Mark Herring on the proposed merger. In August, 2017, Town said that the proposed Cooperative Agreement was unlikely to improve quality and was not necessary to improve the population health of the region. The cost efficiencies it claimed were unverifiable.

Putting aside the objections and concerns of the FTC and Virginia’s independent assessor, on October 30, 2017, Dr. Marissa Levine, Virginia Commissioner of Health, issued the Virginia Order and Letter Authorizing a Cooperative Agreement. “Similar to Ballad’s COPA (Certificate of Public Advantage) in Tennessee, the Virginia Order provides Ballad with state action immunity from state and federal antitrust laws by replacing competition with state regulation and active supervision.”

The formal merger as Ballad Health went into effect on January 31, 2018 when Dr. John J. Dreyzehner, Tennessee Commissioner of Health, issued a Certificate of Public Advantage.

Continued approval is contingent on an annual review of Ballad’s compliance with 49 conditions put into place to ensure that “the benefits from the Cooperative Agreement would be likely to outweigh the disadvantages resulting from the reduction in competition.”

Monitoring the Conditions requires extensive reports and uses two full-time monitors, one in Tennessee and one in Virginia, both states’ health departments, and a Task Force involving the Southwest Virginia Health Authority (SVHA). In Virginia, a Cooperative Agreement Active Supervision Committee meets at least quarterly and works with the core VDH staff team. (Tennessee involves additional groups in monitoring as well.)

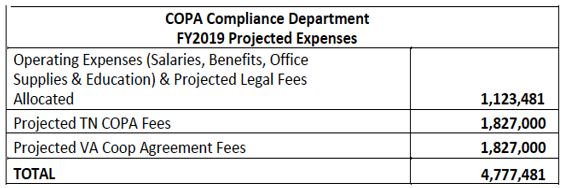

In one of the 49 conditions, Ballad agreed to pay $2.5 million toward the monitoring cost for both states. The Tennessee COPA Compliance Office showed a considerably higher estimate of the total monitoring costs for Fiscal Year 2019 in its Fiscal Year 2018 report. In other words, the two states are absorbing more than $2 million in regulatory oversight costs.

In Part 2 of this series, “Ballad Health Merger – Cuts and Consolidations,” we will explore how Ballad used the merger to cut costs.

Carol J. Bova is a writer residing in Mathews County.