Under withering criticism for a lack of transparency, the Commonwealth Transportation Board has agreed to a one-month delay before formally endorsing the McDonnell administration’s vision for the North-South Corridor.

by James A. Bacon

Transportation Secretary Sean Connaughton, a former chairman of the Prince William County board, is a key driver behind the North-South Corridor.

In deference to a scathing letter from Congressman Frank Wolf, R-10, and personal appeals from two members of the General Assembly, the Commonwealth Transportation Board voted Wednesday to delay formal acceptance of the Northern Virginia North-South Corridor Master Plan by a month.

Any recognition of the master plan would have been purely symbolic — it represents no more than an aspirational vision for a north-south multimodal corridor west of Washington Dulles International Airport. Blocking the plan would not thwart any of the specific projects discussed within it. And the deferral was equally symbolic. Not a single member of the CTB expressed reservations of any kind about the plan. Its acceptance in June seems pre-ordained.

But in the trench warfare over new transportation projects, warring parties place great stock in even symbolic victories and defeats. And opposition to the linchpin segment of the 45-mile North-South corridor, the so-called Bi-County Parkway (also referred to as the Tri-County Parkway), is intense. The crux of the conflict centers on the alleged necessity of routing the Parkway through or around the Manassas National Battlefield Park. The interests of stakeholders as varied as the McDonnell administration, the National Park Service, Northern Virginia commuters and residents of nearby farms and subdivisions seem largely irreconcilable.

Approval of the Bi-County Parkway, which is moving along its own bureaucratic track, is not contingent upon acceptance of the North-South master plan. But accepting the master plan would confer legitimacy upon the Parkway. And that was enough to goad several Prince William County residents to travel to Richmond to address the CTB and to inspire two elected officials, Del. Tim Hugo, R-Centreville, and Bob Marshall, R-Manassas, to endure four hours of CTB tedium in order to speak on the behalf of constituents who had packed previous Northern Virginia gatherings to protest plans for the parkway.

“Normally, we can’t get 15 people to a town hall meeting. We had 400 people show up,” Hugo told the CTB. “Congressman Wolf is not a flamethrower. I’m not a flamethrower.” But both are concerned by how the project is progressing. The Bi-County Parkway, the delegate said, will create “a traffic armageddon.”

But the Parkway had its defenders, including representatives of the Loudoun County and Prince William chambers of commerce and an aide to Loudoun County Board Chair Scott York. Brian Fauls, manager-government affairs for the Loudoun Chamber, said Loudoun needs a north-south highway to improve access to Dulles airport. Like the ports in Hampton Roads, Dulles is regarded as an economic engine of the state. But unlike Hampton Roads, which is served by five existing Corridors of Statewide Significance, Dulles is served by none. The North-South corridor would remedy that deficiency.

Richard McCary, past-president of the Committee for Dulles, also pointed out that the corridor is needed to serve the massive population growth in eastern Loudoun/western Prince William projected by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

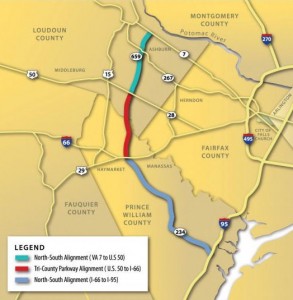

The Master Plan outlines several components to the corridor. One piece already exists — Rt. 234 (the Prince William Parkway), which runs from Interstate 95 to Manassas. The corridor would continue north past the Battlefield Park and through the rural, western reaches of Prince William County — the Bi-County Parkway — and then tie into a northern segment aligned with Northstar Boulevard in Loudoun. Additional pieces of the corridor would include an east-west link to Dulles airport and a widening of Rt. 606 on the airport’s western edge. VDOT has not yet developed a cost estimate for the projects.

The great sticking point is the middle segment where it would run along the western edge of the battlefield and through the so-called “rural crescent” of Prince William. According to the latest version of a deal negotiated between the National Park Service and the Virginia Department of Transportation, the Bi-County Parkway would align with the western half of a proposed battlefield bypass. When the Bi-County parkway is built, park authorities would close Rt. 234, a parallel north-south road that runs through the center of the park, and install unspecified traffic-calming measures on a section of U.S. 29 that runs east-west through the park. Traffic on those two roads, which park officials say disrupts the visitor experience, carry roughly 24,000 cars a day. In theory, completing the eastern half of the bypass will improve conditions for east-west commuters, but no one has identified a source of funds for that project. Continue reading.