Del. Keith Hodges introducing a substitute for HB 1774.

By Carol J. Bova

Virginia’s part-time legislators saw 3,168 bills introduced in the 2017 General Assembly session according to the Richmond Sunlight website. Inundated with such a volume of legislation, overworked part-time lawmakers are hard-pressed to grind through complex issues.

In such circumstances, speeding bills through the legislature can lead to bad law. And that appears to have been the case with a bill, enacted in the 2016 session, that put into place stormwater management legislation due to go into effect July 1, 2017.

Alerted to deficiencies in that law, lawmakers took up the issue again in the 2017 session. The issues got so ticklish and hard to resolve that legislators threw up their hands and passed a bill that delayed implementation of the original law and gave them a year to reconcile the many conflicting interests.

Del. Keith Hodges, R-Urbanna, took the lead on updating the stormwater law this year. He submitted three interrelated bills, which he wrote with the assistance of the Virginia Coastal Policy Center of William and Mary Law School and the Middle Peninsula Planning District Commission. One of the bills, which allows jurisdictions to outsource administration of the stormwater law to third-party engineering firms, was uncontroversial and sailed through the House and Senate.

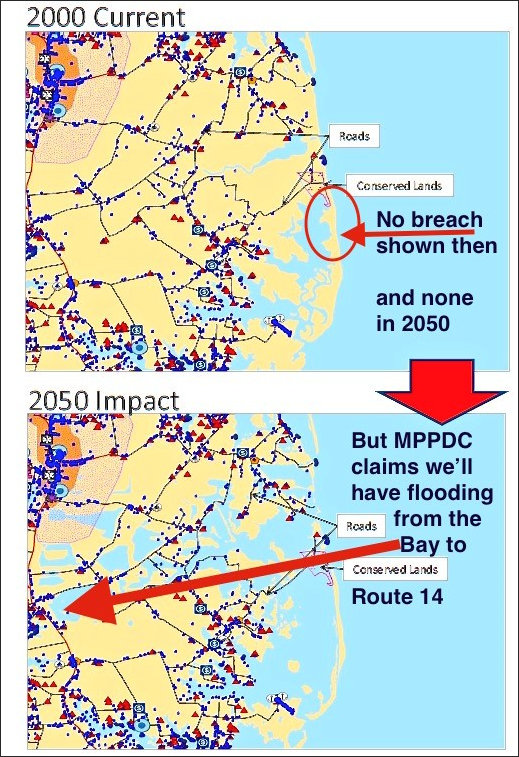

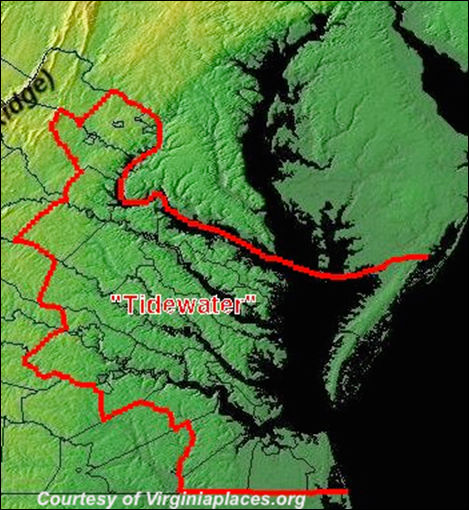

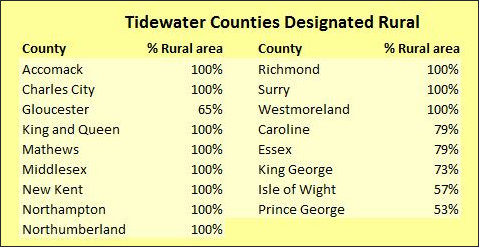

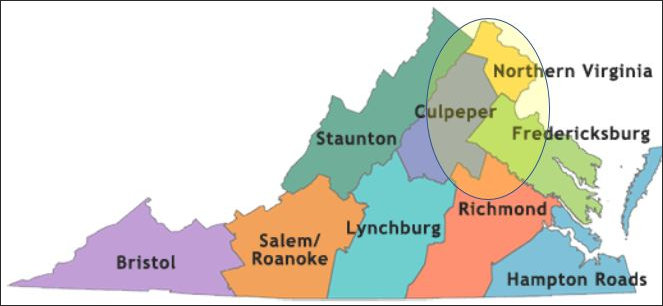

But the other two, HB 1774 and HB 2008, got tangled up in the legislative process. The main sticking point was how to deal with a loophole in the law going into effect in July that set different triggers at which counties had to put into place stormwater management programs. For most of the state, the regulations apply when a project disturbs 10,000 square feet of land up to one acre (at which point the Department of Environmental Quality steps in). But for the 29 counties and 17 cities defined in state law as “Tidewater,” which have the greatest potential to affect water quality in the Chesapeake Bay, the requirement kicked in at 2,500 square feet.

The Virginia Association of Counties (VACo), the lobbying arm of local governments, took the position that the 2,500-square-foot trigger was too onerous and described the closing of the “donut hole” — between 2,500 and 10,000 square feet — as one of its primary objectives of the 2017 session. HB 2008 would have accomplished precisely that.

However, at some point during the session, Hodges concluded that even the 10,000-square-feet trigger was too tough. Counties wanted out because they are not in the business of managing the erosion and stormwater impacts of land disturbance. They would have to add staff and find funding from already strained budgets. Counties with little new construction would not generate enough permit fees to offset the costs when they occurred, while even counties experiencing modest growth had no guarantee new fees would be sufficient.

Accordingly, Hodges withdrew HB 2008.

That left HB 1774 as the main vehicle for fixing the soon-to-be-enacted law. Like the Indian parable of several blind men trying to discern the nature of an elephant, the bill seemingly offered something to all the special interests involved in stormwater management:

- New business opportunities for engineering firms — if there is a source of funding to create the stormwater management facilities.

- Improved Chesapeake Bay water quality — if the new Regional Stormwater Best Practices facilities (RSPs), or stormwater banks, work as advertised. (See previous story for details.)

- New rural economic development — if new RSPs actually do reduce costs for developers.

- New income for localities from the sale of stormwater mitigation credits to developers — if there is an excess to sell and if there is water to treat in the first place.

- Relief for the Virginia Department of Transportation of obligations for roadside drainage by transferring exclusive use of the water in its ditches to new stormwater management facilities — if the water remains in the ditches and if VDOT can ignore the rights of downstream parties to use of the water.

- Administrative savings for DEQ — if localities agree to take over the stormwater management and if the 2% of fees paid by developers for excess credits offset the $490,000/year extra in salaries for monitoring.

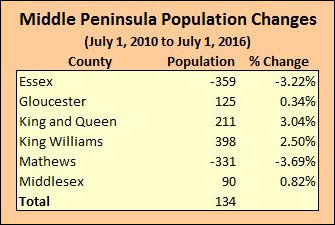

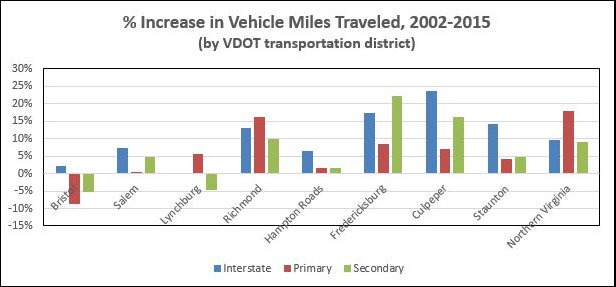

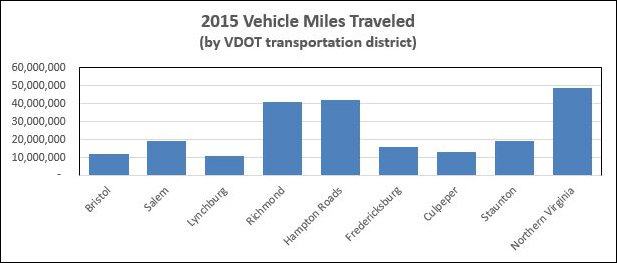

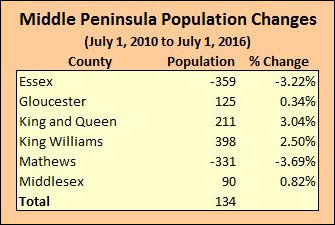

It all works if the system has enough money. Trouble is, rural counties just aren’t experiencing the kind of population and commercial growth to generate the fees to make all these things happen. The five-year census update estimate from the Weldon Cooper Center calls the premise into question.

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :

“While population growth continues or accelerates in most of Virginia’s urban areas, much of rural Virginia will likely continue to experience slow population growth or decline during this decade.”

With all these problems, including the $2.45 million expense to hire DEQ employees to monitor the project, what happened to HB 1774? The House committee didn’t kill it. The legislators requested a substitute bill.

To be continued in Part Three — Starting Over

Carol Bova is author of “Drowning a County: When urban myths destroy rural drainage,” a book documenting VDOT’s neglect of its highway drainage in Mathews County.

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :