An Amazon home-delivery drone. Private-sector applications of unmanned systems would fit nicely with Virginia’s economic development priorities.

In the lead-up to Amazon, Inc.’s announcement that it would split its massive HQ2 expansion between Northern Virginia and New York, there was considerable speculation that Northern Virginia had an edge among the 20 finalist regions due to its proximity to the federal government. The company was aggressively vying for federal government business, most visibly in cloud services, and Amazon, like other federal contractors, needed a Washington location in order be close to the world’s biggest customer of IT services.

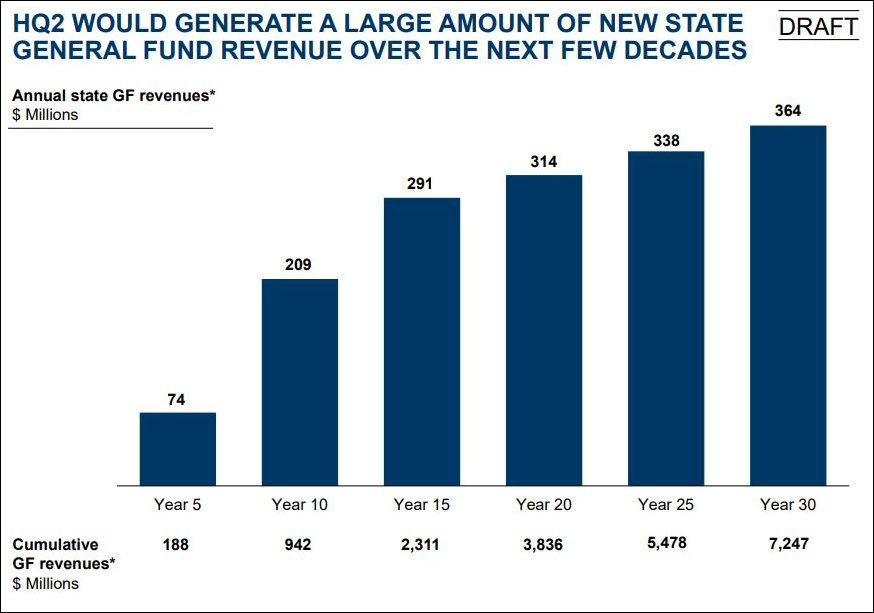

But Amazon’s decision to locate in Arlington practically next door to the Pentagon is not a federal government play, says Stephen Moret, CEO of the Virginia Economic Development Partnership. Furthermore, Virginia is not shelling out an unprecedented $550 million in job-creation inducements by FY 2035 (plus up to $200 million more in later phases) to magnify Northern Virginia’s dependence upon federal government spending.

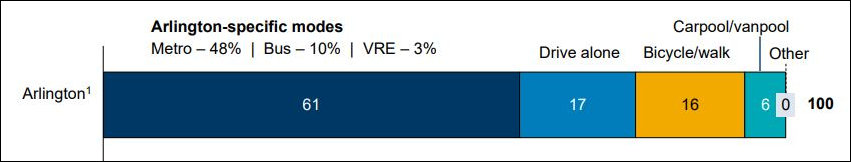

The Amazon expansion is driven mainly by private-sector initiatives, says Moret, and Virginia’s incentives package is “right in the bulls eye” of Virginia’s strategic goals of diversifying the economy away from the federal government and bolstering the region’s high-tech industry. “For us, this is principally a private-sector diversification opportunity,” he tells Bacon’s Rebellion. “In terms of the jobs we incentivize, no more than 10% can be associated with federal government contracts.”

That’s why the Amazon-Virginia Memorandum of Understanding requires “a certification as to whether more than 10% of the New Jobs at the Facility during the prior calendar year were primarily engaged in supporting Federal Government contracts, and, if so, the percentage of New Jobs so engaged.” If new jobs tied to federal work exceeds 10% in the new facility, they would not be eligible for state employment incentives.

The percentage of federal-related jobs was not a significant issue in negotiations between Amazon and Virginia, Moret says. VEDP included the language as a “safeguard” to advance Virginia’s diversification goal. “We just wanted to make sure that the opportunity we saw would be ensured by the incentive structure.”

Last June Amazon announced a decision to expand the presence of Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Virginia with a new East Coast campus in Herndon. The deal was expected to create 1,500 new jobs in the cloud computing field. The press release from the Governor’s Office described the business this way: “AWS offers over 90 fully featured services for compute, storage, networking, database, analytics, application services, deployment, management, developer, mobile, Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), security, hybrid, and enterprise applications, from 42 Availability Zones (AZs) across 16 geographic regions in the U.S., Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, India, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and the UK. ”

While AWS was pitching cloud services to Uncle Sam, the list of add-on software applications clearly was aimed at an audience beyond the federal government.

Known primarily as an e-commerce giant and, more recently, as a provider of cloud services, Amazon is expanding into many exciting fields, Moret says. In vying for HQ2, an even bigger investment, VEDP scrutinized the public job postings for Amazon’s Seattle headquarters and found the company was recruiting talent for fields from health care to big data analytics.

Amazon Business, launched in 2012, provides an Amazon.com shopping experience for business supplies. Amazon is expanding its array of consumer electronics products beyond the Kindle e-readers and Echo smart speaker into smartphones TV set-top devices and credit-card readers. The company is pushing into digital streaming of music and games, and with its Whole Foods acquisition is experimenting with the home delivery of groceries. Amazon wants to rationalize the logistics of the health care industry, peddle event tickets online, sell educational toys on a subscription basis, and penetrate the home Internet-of-Things market. (See a list of Amazon products and services here.)

Moret expects new private-sector initiatives will take root in Northern Virginia, enlarging the region’s innovation ecosystem, generating new Amazon business lines, and creating new opportunities for non-Amazon entrepreneurs. Ideally, the new ventures will play to Virginia’s strengths in areas such as unmanned systems, cloud computing, Artificial Intelligence and cyber-security.

Says Moret: “We saw these as big growth opportunities for Virginia.”