“School segregation by race and poverty is deepening in Virginia,” asserts the opening line of a just-published study, “School Segregation by Boundary Line in Virginia.”

The study proceeds to show no such thing.

While it is beyond dispute that de facto segregation persists, especially in inner-city school districts, the study provides no data to support the conclusion that the separation of races is intensifying. Indeed, the authors concede that black student enrollment has declined in urban school districts and increased in suburban districts — thus moving from highly segregated to less-segregated schools.

The main trend in school enrollment over the past decade has been a decline in the percentages of whites and blacks and an increase in the percentages of Hispanics and Asians.

The most original contribution of the study is to examine the effect of the redrawing of school district boundaries by local school boards. Among the 28 school divisions whose rezoning policies the authors studied, the primary motive cited by 20 was to achieve administrative efficiencies. The study provided no evidence that such “rezonings” resulted in more segregated school attendance.

Conversely, eight Virginia divisions — including large systems such as Prince William, Henrico, Albemarle, Suffolk, and Richmond — did explicitly reference the goal of achieving more integration. Three specifically cited “the need to provide cultural, racial and economic balance.”

The lead author of the study, published by the Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State and the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Education, is Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, a well known social-justice activist in the Richmond area. The study is a classic case of scholars finding what they wanted to find. If you’re looking for evidence of discrimination and racism in statistics, you can always find it — even if it means ignoring your own data.

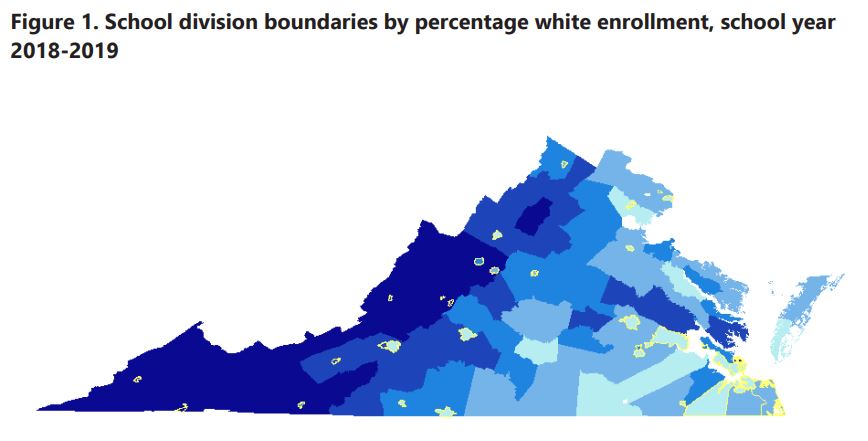

Hawley-Siegel et al use the Thiel’s H statistical methodology to document what we already know — members of racial/ethnic groups in Virginia are not scattered randomly across the landscape. The settlement patterns of African-Americans today is still shaped to some degree by past practices designed to enforce residential segregation. Hispanics and Asians, especially immigrants, tend to cluster in the same neighborhoods. And whites predominate in rural Appalachian counties of western Virginia where poverty rates are high, job creation weak, and in-migration by non-whites minimal.

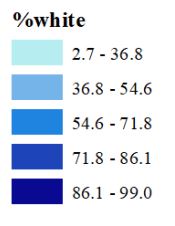

The authors also argue that segregation between schools within the same district contributes to half or more of all multiracial school segregation in Northern Virginia (63%), Central Virginia (56%) and Tidewater (50%). As for the argument that school segregation is getting worse — as in, less diverse — here is the only evidence in the report I could find:

Translation: Over the decade between the 2009/10 school year and the 2018/19 school year, elementary schools became slightly less diverse, but middle and high schools became more diverse. Because there are almost twice as many elementary schools as middle and high schools combined, it looks like school systems overall crept toward greater segregation. However, if we measured students rather than schools, we’d get a very different result. Because there are 35% more students in middle and high schools than in elementary schools (2020-21 enrollment figures), this comparison would suggest that there is more diversity and less segregation overall than there was 10 years ago.

The authors also state, with no evidence whatsoever, that “these invisible boundaries acquire strong social meaning flowing from the unequal allocation of educational resources.” Bacon’s Rebellion has demolished the stereotype of under-funded black schools in Virginia. School allocations to schools is remarkable equal within school districts.

Siegel-Hawley et al might counter that the funding for schools serving high concentrations of poor and minority students is inadequate “relative to student need.” “Largely because of difficult working conditions, schools serving high concentrations of color and students in poverty experience higher rates of leader, teacher and student turnover.”

That is likely true. Whether inadequate funding is the problem that ails poor-performing schools is debatable, and a question for very different study.