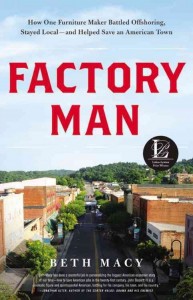

This is a review of “Factory Man,” a book about the Virginia furniture business and dealing with the inequities of Chinese trade by Beth Macy (Little Brown, 451 pages). This was first published in the October 2014 Bulletin of the Overseas Press Club of America in New York of which I am a member.

The hills around Danville Va. are blessed with some of the finest hardwoods around such as oak, hickory and cherry trees. It is those trees, and the people who work with them, that have made for one of the more vicious global trade wars in recent history.

They also represent one of the few trade victories American industry has had, according to Beth Macy, a Roanoke Times reporter who has written a lively and deeply reported book about Vaughan Bassett, a local firm that is now the largest American furniture maker. Boss John D. Bassett (“JBIII”) refused to succumb to an onslaught of cheap Chinese labor and government subsidies that helped shutter 63,300 U.S. factories and five million jobs from 2001 to 2012. By standing up to Beijing, he saved his company and 700 jobs.

Macy’s first book is of value to anyone who covers global trade issues. She punctures the conceit, held by many journalists in the New York-Washington axis, that globalization is a great and inevitable thing. I heard this constantly at BusinessWeek where I worked as an editor and bureau chief in the 1980s and 1990s.

What’s lost in the laud of so-called “free” trade is what happens to the people who lose. Their secure employment turned overnight into a new world of Medicaid, food stamps and family strife.

Big Journalism doesn’t seem to care much. “Even globalization guru Tom Freidman, writing in “The World Is Flat,” briefly acknowledges the agony caused by offshoring.” But she notes that it’s easy for him to say since Friedman, “lives in an 11,400 square foot house with his heiress wife” in Bethesda, Md., a “cushy” Washington suburb five hours by car from the turmoil farther south.

For years, Bassett and its sister factories were part of a network of Southern-style company towns with their own issues, such as paying African-American workers half of what whites got. By the 1970s, U.S. furniture quality and productivity were slipping. A Taiwanese chemist discovered how to make rubber trees useful for furniture after they stopped producing latex, giving rise to an expanded Asian export furniture business.

Chinese industrialists took over. They visited U.S. factories, where, according to Macy, naïve executives handed over their production secrets. In short order, cheap Chinese knockoffs were stealing market share from the Americans. A Chinese executive named He Yun Feng bluntly suggested to JBIII that he shut his plants and hand his business over. Proud JBIII didn’t turn tail. Instead, he shored up his production and cut costs while preserving as many jobs as he could. He also bucked his reluctant industry and challenged the Chinese for dumping and manipulating their currency to give them unfair trade advantages.

“The last thing they wanted to hear was that China may have been breaking the law.” Macy quotes JBIII as saying. That’s the nut of Macy’s excellent book. A tighter edit, especially in the early history of the Basset family, might have helped, but her story is powerful and well told.

OPC member Galuszka lives in the Richmond, Va. area and is author of “Thunder on the Mountain; Death at Massey and the Dirty Secrets Behind Big Coal” St. Martin’s Press, 2012.