The Commonwealth is experiencing a crisis in its mental health system. The situation is the result of some positive initiatives of the General Assembly, coupled with the legislature’s reluctance to provide the funding needed to deal with the results of those initiatives.

The Commonwealth is experiencing a crisis in its mental health system. The situation is the result of some positive initiatives of the General Assembly, coupled with the legislature’s reluctance to provide the funding needed to deal with the results of those initiatives.

The crisis is an acute shortage of mental health treatment beds. Around the first of this month, the Commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS) warned “there will be times over the July 4th holiday weekend when there will not be any open staffed beds at any of the state hospitals.” And the July 4 weekend was not an aberration. The state’s adult mental health hospitals operated at 98 to 100 percent capacity in May and June. One day this month, the two hospitals that treat elderly patients had more patients than beds.

The state has reduced its mental health bed capacity in recent years, going from 1,571 beds in June 2010 to 1,491 beds in FY 2020, a reduction of five percent.

During that period of decreasing bed capacity, the General Assembly took two actions that have resulted in a significant increase in mental health admissions.

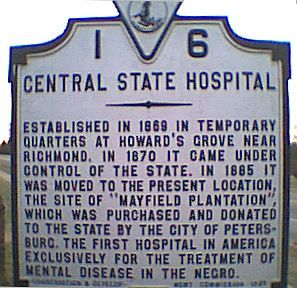

The first dealt with persons ordered by the courts to be examined for their mental competency to stand trial. In the past, such defendants could languish in jail for weeks, even months, until the state mental health system could accept them for evaluation. Legislation enacted in 2014 requires such persons to be admitted to the mental health facility within 10 days of the court order. That immediately put pressure on the mental hospitals that performed such examinations, primarily Central State Hospital, but also Eastern State Hospital. (See here.)

The measures that had the largest effect were adopted in response to the tragedy of Sen. Creigh Deeds, whose son seriously wounded him and then killed himself after being released from custody when no mental health bed could be found. A person experiencing a mental health crisis can be taken into emergency custody by law enforcement. At that point, law enforcement or, more likely, community services staff have several hours to find a mental health hospital in which to place the person under a temporary detention order (TDO). If no bed is found within the allotted time, the person must be released. Once admitted, the mental health hospital has three days to evaluate the person, after which a court may order the person’s involuntary commitment. The legislation required the establishment of a registry of mental health beds, lengthened the time that community services has to find a bed for someone in emergency custody, and made the state hospitals the bed of last resort and required to accept a TDO if no other bed is available.

The result of these measures has been a significant increase in the number of TDOs—almost 300 percent increase since 2013. (In addition to the longer time given to look for a bed, the creation of a bed registry, and the requirement that the state be the bed of last resort, I speculate that there may be another factor underlying the increase in TDOs. In light of the large amount of publicity accompanying the Deeds tragedy, magistrates may be more likely to issue a TDO for persons who might be showing marginal symptoms of mental distress and might not have been committed in the past.)

TDOs can be placed in private mental facilities, as well as the state facilities, and many are. However, private hospitals do not have to accept a TDO referral from a community services agency. Moreover, they are also seeing a significant increase in the number of voluntary admissions. Officials of those hospitals attribute some of that increase to the increased understanding of the general public that mental illness is a disease and not a moral defect. There is not as much stigma attached to asking for help. As a result of the increase in involuntary commitments and voluntary admissions, private hospitals are increasing their bed capacity. (For fuller details, see here.)

And what has the General Assembly been doing? There is a special commission headed by Deeds that is examining the myriad of issue swirling around the mental health system and making recommendations. But there has been little movement to increase system capacity. DBHDS has been requesting for several years the authority and funding to demolish the decrepit Central State Hospital in Petersburg and replace it with a larger facility. Its capital budget request to the 2019 General Assembly was for a 300-bed facility (only a slight increase over the current bed capacity of 277), at a cost of $373 million. Recoiling at the cost, the General Assembly balked, relenting only at the last minute under a lot of pressure from the administration. But, the legislature decreased the authorized capacity of the new facility to 252 beds (fewer than the current capacity), with an estimated cost of $315 million.

The General Assembly did hedge its bet some, however. There is budget language directing DBHDS to coordinate with a special legislative workgroup to “develop a conceptual plan to ‘right size’ the state behavioral health hospital system.” The language goes on to direct the department to include as a part of the plan” a proposal for construction of a new Central State Hospital” with a scope within a “right-sized” system. Never mind that the department had submitted a 403-page study to the General Assembly relative to Central State in December 2018. Let’s kick that can on down the road.

Furthermore, the General Assembly seems to have been taken aback by the “success” of its measures regarding TDOs and the resultant surge in admissions to state hospitals. There is budget language establishing a special workgroup “to examine the impact of Temporary Detention Order admissions on the state behavioral health hospitals. The workgroup shall develop options to relieve the census pressure on state behavioral health hospitals, which shall include options for diverting more admissions to private hospitals and other opportunities to increase community services that may reduce the number of Temporary Detention Orders.” It sounds as if the legislature is having second thoughts about its earlier actions and is looking for ways to walk those actions back. Also, note the lack of any mention of increasing the capacity of the state system.

These two groups are supposed to report in the fall. It will be interesting to see what they come up with.

Hall-Sizemore Soapbox—There have been three positive developments in the Commonwealth regarding the treatment of persons with serious mental illnesses:

- Quicker admission and evaluation of persons for mental competency to stand trial;

- More time and tools to help community services staff to find a treatment bed for persons experiencing a mental health crisis, along with a mandate that the state accept such persons if no other bed is available;

- More acceptance of mental health illness by the general public, with less stigma being attached to asking for help.

All of these developments have led to more people being admitted, voluntarily and involuntarily, to private and public mental health facilities. This bodes well for those persons needing help. Instead of cutting back on new capacity in order to save some money, looking for ways to walk back the progress that has been made, and generally kicking the can down the road once again, the General Assembly needs to be accountable and assume responsibility and provide the funding and leadership to deal with the results flowing from the positive measures it enacted in prior years.