by Dick Hall-Sizemore

The recent posts and comments concerning the reversion of the city of Martinsville to town status (see here, here, and here) provide a good opportunity to discuss the complexity of local government finance and the limitations of using simplistic measures to compare governments.

Jim Sherlock referred to the “wreckage” of Martinsville, which he attributed to “decades of Democratic control.” When asked to define “wreckage,” he referred to the city government overspending to a “negative ROI” and declared that “the first job of any government in Virginia is to live within its means.” The obvious implication is that Martinsville spent more than it took in.

The only specific evidence offered to support the Martinsville “wreckage” charge was the higher spending per person by Martinsville and the higher tax rate in the city.

Local government finances is a fairly complex subject, but there is a good amount of data online for anyone who wants to dig. The website of the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts serves as the base for most of this data. Its annual Comparative Report of Local Government Revenue and Expenditures is the basic document. It contains a great deal of data, but it has its limitations, as will become clear later in this discussion. The website also has the annual financial report of each local jurisdiction, which can provide even more insight for those experienced at reading and understanding financial reports (which I am not).

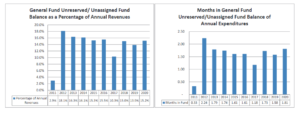

Sherlock offered no evidence to substantiate his assertion that Martinsville has a “negative ROI” (I do not know what term means in the context of government) and that the city has spent beyond its means. However, the city’s audited financial report demonstrates, as shown in the graph below, that the city has had an unrestricted general fund year-end balance for each of the past ten years. Clearly, it has not spent beyond is means.

Source: Martinsville 2020 Annual Financial Report, http://www.apa.virginia.gov/data/download/local_gov_cafr/Martinsville%20CAFR%202020.pdf

Next is the charge that Martinsville has a higher tax rate than Henry County and spends more per capita than the county does. Of course, it does. It provides a higher level of services to a denser population than Henry County does. That is what makes it a city. And, it should come as no surprise. Virtually every city in the Commonwealth has a higher tax rate than adjoining counties.

In addition to disparate service levels, counties enjoy economies of scale. Although Mr. Sherlock dismissed this argument, such an advantage does exist. Being able to spread certain common fixed costs, such as a city or county manager’s or school superintendent’s salary over its population of 51,000, rather than Martinsville’s 13,000, will result in a lower per capita cost for Henry County.

Several specific services can serve as examples of disparate service levels. The starting point for the data is the APA’s 2020 Comparative Report. Each city and county in the Commonwealth receives state financial assistance for specific services and programs. However, if one is trying to compare the spending of its own revenues by a city or town for a specific service to comparable spending by another jurisdiction, one needs to back out the state funds. It is here that the APA report has limitations. It reports total local revenues by source, but does not break the spending for specific services down by revenue source. To accomplish that, one has to use the reports of the agencies from which the revenues came.

For each of the service areas considered below, I have adjusted the spending reported by Martinsville and Henry County in the APA report by the state funding received for that service. Note: the resultant spending amounts are certainly not completely “clean”; they are likely to include federal and additional state grant money. I have adjusted only for the major, continuing sources of state aid. To do more would require more resources that I have access to and more time than would be justified for this exercise.

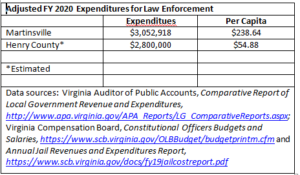

Law enforcement

The city has a police department that provides law enforcement and traffic control services. In the county, the sheriff provides those services, supplemented by the State Police.

Both the city and the county receive state financial assistance for law enforcement. In FY 2020, Martinsville received a little under $1 million in HB 599 funding. For sheriffs, the Compensation Board reimburses localities for the total cost of the sheriff’s salary, as well as the total cost of all approved deputies. (Most localities, including Henry County, employ, at their cost, more deputies than approved by the Compensation Board.)

Determining the cost of law-enforcement in local funds for the county is complicated by the sheriff being responsible for law-enforcement, running the jail, providing court security, and serving legal process. (Martinsville also has a sheriff, but he is not responsible for law enforcement.) Without additional data that is not readily available, it is not possible to determine how much Henry County spent in local funds for law enforcement by the sheriff. However, using Compensation Board data that is available online, it is possible to estimate that cost.

The table below shows the adjusted FY 2020 Martinsville cost for law enforcement and an estimate of the cost for Henry County in local funds.

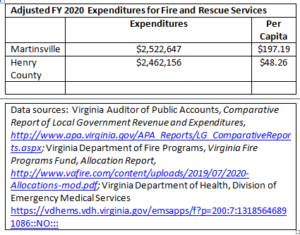

Fire and Rescue Services

To provide fire and rescue services within its 11 square miles, Martinsville has two stations consisting of two engine companies, one ladder company, a rescue truck and two advance life support ambulances. Its personnel are cross-trained in both fire and EMS.

In contrast, Henry County relies primarily on eight volunteer fire companies and five rescue squads to provide those services within its 382 square miles. The county does provide some full-time and part-time EMT and paramedic-firefighters to assist the volunteers.

Both jurisdictions receive state financial assistance from the Department of Fire Programs and the Department of Health for these services.

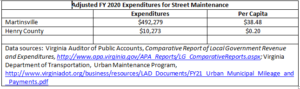

Street Maintenance

The state maintains all the roads in Henry County.

Martinsville is responsible for maintaining streets, bridges, and sidewalks within its boundaries. However, the Virginia Department of Transportation provides the city financial assistance under its urban street payment program.

Tax rate increase

Sherlock echoed the county claims and fears that a Martinsville reversion would result in massive tax increases for the county. He also referred to the increase in taxes on residents and businesses in the city as a result of “double taxation” by the town and county.

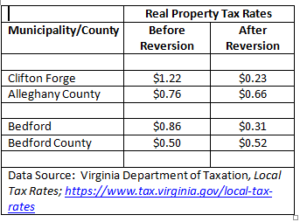

The history of city-town reversions in Virginia suggests that these fears are unfounded. The following table shows the pre- and post-reversion tax rates in two of the three city-to-town reversions that have occurred. In both cases, county residents and businesses had either a lower, or only slightly higher, tax rate and the combined tax rate for town residents and businesses was lower than the city tax rate before reversion. (Available on-line data does not go back far enough to enable such a comparison of tax rates relative to the South Boston reversion in 1995.)

My Soapbox

My Soapbox

Obviously, this has not been anywhere near a thorough analysis of the relative financial conditions of Martinsville and Henry County and their level of services. I do not have ready access to sufficient data, nor do I have the experience, to do so. That will be the job of the staff of the Commission on Local Government as it analyzes the proposed agreement and makes a recommendation to the court that will consider it.

My aim has been to use the Martinsville reversion situation as an example of the complexity of local governments and their finances. Relying on simplistic measures such as per capita expenditures and tax rates is likely to produce an incomplete or misleading conclusion.