by James A. Bacon

The average life expectancy in the affluent West End of Richmond is 83 years. The comparable number for residents of Gilpin Court, a public housing project in the east side of the city, is about 60 years. How do we explain that discrepancy?

The conventional wisdom attributes the health gap to socioeconomic differences — Social Determinants of Health, in academic lingo — and there is no denying the close relationship between income, education and health. The better educated you are and the higher your income, the longer you are likely to live. Affluent Virginians are far more likely to have health care insurance, which ensures better access to health care, less likely to be exposed to environmental hazards, and more likely to hang out with other people who influence them to exercise, control their weight and embrace other healthy behaviors.

But is that the whole story? An article this morning in the Times-Dispatch, slugged “Where you live determines how long you live,” explores health disparities in the Richmond region. The reporting draws heavily upon the 2012 report on health equity by the state Office of Minority Equity and Health Equity (OMEHE), which mapped the disparity in health “opportunities” region by zip code. The report uses a Health Opportunity Index that encompasses factors such as education, exposure to pollutants, affordability of transportation and housing, job participation, racial diversity, material deprivation and other factors.

Trouble is, by imposing a socioeconomic framework on the problem, policy makers bias themselves toward a socioeconomic analysis and wind up recommending socioeconomic solutions. Thus, in the words of Michael O. Royster, until recently the director of OMEHE, to fix health disparities we need to increase job opportunities for the poor, improve educational outcomes, reduce exposure to air toxins and generally “develop policies, programs, and practices within organizations and communities that support racial, economic and gender equality.”

Royce goes so far as to suggest that African-Americans are more likely to report (24.6%) experiences of perceived racial discrimination than whites (5.7%) or Hispanics, and that those who perceive themselves victims of racial discrimination also are more likely to report poor health. Perceived racial discrimination, he says, is associated with hypertension, substance abuse, depression and and psychological distress.

In other words, the onus is on society to improve health outcomes for minorities. The solution is more government.

While inequitable access to health resources undoubtedly is a contributor to the longevity gap, in my view, any approach that fails to address the disproportionate tendency for poor people of all races to smoke, drink too much, overeat, get insufficient exercise, use illegal drugs, engage in unsafe sex and physically assault one another with guns, knives and cudgels — in other words, that fails to grapple with the culture of poverty — is missing the boat.

As I noted in a previous blog post, “Murders, Accidents and Public Health,” tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and problem drinking are associated with 40% of all deaths in the United States. Moreover, among African-Americans, a significant portion of the longevity gap can be explained by the dramatically disproportionate number of young males who are murdered.

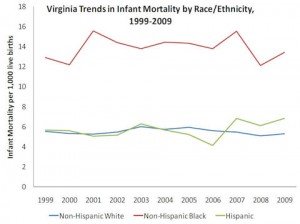

For an example of how culture affects health care outcomes, consider this: Hispanics in Virginia rank lower than African-Americans in educational attainment, only a little higher in average income, and considerably lower in medical insurance coverage, yet they rank far lower in the incidence of low birth-weight births. Indeed, between 1999 and 2009, according to Royce’s own statistics, Hispanics have consistently ranked lower than whites in the incidence of low birth-weight. What accounts for the difference? Can you say, culture?

A fundamental problem that Royce acknowledges only glancingly is the prevalence of social isolation and the poverty of social connections between family, friends and neighbors in poor neighborhoods. We’re talking about family breakdown and, other than the church and outside not-for-profit groups, the near total absence of civil society. If you’re looking for underlying causes, the social isolation America’s poor is huge.

Royce strays perilously close to acknowledging the role of culture when he notes, “Immigrant groups, on average, have better health status than native born Americans. Unfortunately, this health advantage deteriorates the longer immigrants remain in the United States. Health outcomes of children of immigrants and successive generations more closely mirror the health of native-born Americans.” Perhaps one thing that immigrants bring with them, and later lose, is strong family ties. Again, can you say, culture?

If our interest is to actually help poor people live healthier lives — as opposed to perpetuating the dogma that only an activist state can redress social ills — then we need to adopt a very different way of looking at poverty.