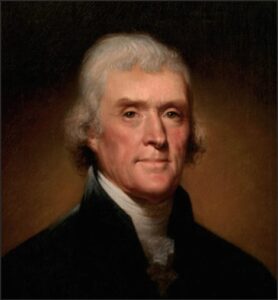

Critical Race Theory and Identity Politics advocates have gained enough influence to cause many Americans to despise some of our country’s most significant founders. Chief among such founders has been Thomas Jefferson. New York City, for example, removed a 200-year-old statue of Jefferson from its city hall last year.

When race hustlers can persuade us to despise Jefferson, they’re well on their way to transforming America into a country that hates our traditional values. Unlike other countries, America was not founded because her people were of a common race. The nation was founded on ideals that united us. It was organized as a constitutional republic with no ruling family, thereby proclaiming the political equality of all her citizens whom she invested with the freedom to pursue their own interests with minimal government interference. Present attacks on founders focus on what they did not do as opposed to what they did accomplish. Although they didn’t abolish slavery, they did indeed organize the freest country in history.

When founded, America had but three million people, the current population of Iowa. At the time, the thirteen colonies were little more than a remote backwater on the world stage, but they bloomed into one of the most powerful nations on Earth within a century and a quarter. The contrast between Jefferson’s denunciations of slavery and his failure to put them into practice, make him an easy target. Yet the first gift Jefferson gave to America was her independence. His language of the “self-evident” truths left a lasting mark. His Declaration of Independence asserted that certain rights linked to those truths should be universal, not merely applicable to thirteen colonies. If Jefferson falls victim to cancel culture, there may be no stopping a George Washington takedown as well.

Although his participation in slavery is the obvious flaw in the reputation of a founder who wrote “all men are created equal,” many Americans today believe that slavery was unique to our Southern states. In truth, slavery was legal in all thirteen colonies in 1776. In 1890 Lincoln’s two private secretaries wrote in a ten-volume biography of the former President that, “[Lincoln] believed the people of the North were as responsible for slavery as the people of the South.” Less than three months before the Civil War ended Lincoln told Secretary of State Seward, “If it was wrong in the South to hold slaves, it was wrong in the North to carry on the slave trade and sell them to the South.” Moreover, during the four hundred years of trans-Atlantic slave trade only about four percent arrived in America. Most of the others went to Brazil and the Caribbean.

Even though the Declaration’s “all men are created equal” phrase was an obvious contradiction from the beginning, Martin Luther King took the correct perspective. He realized that slavery could not have been abruptly ended in 1776 without aborting the birth of our country. Thus, he interpreted Jefferson’s Declaration as a “promissory note” to be redeemed at the right time. The Declaration ultimately made it impossible for slavery to continue indefinitely. When the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery was ratified in December 1865 the pre-Carpetbagger, all-white legislatures of eight of the eleven former Confederate states voted in favor of it. A ninth, Florida, followed by the end of the same month.

Historian Jerrett Stepman writes, “It is easy to condemn Jefferson and the Founders for not doing enough to extinguish a social system now universally reviled when we don’t have to deal with the complex consequences of abolition. Slavery was woven into the cultural and economic fabric of American society, and it could not be so easily removed even by those who deeply hated it. Given this reality, it is perhaps less remarkable that they failed to immediately rid themselves of it, and more remarkable that their efforts put it on the inevitable path to extinction.”

When today’s Americans condemn Jefferson for failing to free his slaves, few realize the obstacles that confronted manumission in his era. Many Southern states had laws that did not permit slaves to be set free unless their former masters left them in a condition in which they were unlikely to become destitute and, therefore, a burden on the state. Consistent with the nature of farming, many plantations were heavily in debt. As in the North, when debts went into default, creditors were permitted to seize assets and sell them to pay off the debts. In the South, slaves were among such assets. To prevent a plantation owner from stripping his estate of slaves, Virginia passed a law in 1792 that gave creditors the power to seize even some freed slaves to satisfy debts. Often those creditors were ultimately Northern banks. Without such a law, owners might have been more often tempted to free their slaves in their wills.

When he was 45 years old, six years before being elected President, Abraham Lincoln said, “When the Southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery, than we; I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists; and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself.”

In recent decades Jefferson has been increasingly accused of fathering at least one child by a slave named Sally Hemmings. Until then most historians dismissed the arguments as stemming from the revengeful allegations of a disgruntled former Jefferson political supporter and journalist, James Callender. In 1998 DNA testing showed that at least one of Sally’s children, Eston, shared genetic heritage with the Jefferson family. Yet the father remains unknown because there are over two dozen potential candidates for paternity.

Nevertheless, as cancel culture gained momentum the administrators at Jefferson’s Monticello memorial tried to end the debate in 2018 by declaring Eston to be Thomas Jefferson’s child. In truth, it is far from settled fact. Next, social justice historians added two-plus-two and got twenty-two by claiming that Sally was raped. Yet when Thomas Jefferson served as ambassador to France, he took Hemmings and a male slave to Paris with him. Even though slavery was illegal in France, Hemmings never petitioned for her freedom, as might be expected if Thomas had raped her. We can never know what truly happened, if anything, between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings, but that doesn’t stop the allegation of a relationship being used as a handy club by Jefferson’s detractors.

The current focus on historical slavery has left one of Jefferson’s most significant contributions almost unnoticed. Specifically, as a proponent of an agrarian economy he left a legacy of property ownership. When he became President in 1800 America had more property owners than did all of Europe even though the Old-World countries had thirty times the population. The statistic was a harbinger of the great property-holding middle class that would make America an economic powerhouse, even though not predominantly agrarian.

During his presidency Jefferson enlarged the opportunities for property ownership by acquiring the Louisiana Territory. This frontier would become the destination for land-hungry European immigrants for more than a century. If not purchased by Jefferson, states in the region would have become the properties of French or Spanish monarchs. It is, therefore, ironic that present Louisiana Democrats have minimized the state’s connection to Jefferson. Without him the state would have become part of a European empire, before perhaps transitioning into an impoverished nation like Mexico. In fact, without the Southern presidents of Jefferson and Polk, America’s present western border would be the Mississippi River, not the Pacific Ocean.

Phil Leigh publishes the Civil War Chat blog. This column has been adapted from an excerpt of his new book, “The Dreadful Frauds: Critical Race Theory and Identity Politics.