by Kerry Dougherty

I’m almost never satisfied with my writing. That’s why, if you read one of my posts in the morning and go back in the afternoon it will be slightly different. I can’t stop tinkering.

Over the years I’ve written a handful of pieces that I thought were pretty good. This is one. I’ve shared it before, but I’m posting it again today for those who may have missed it or don’t mind reading it again.

The reason for offering you this today will be obvious to anyone who reads to the end.

I can remember exactly where I was on September 16, 1998. I remember what I was wearing, the cup of 7-Eleven coffee that went cold on the tray table and the way the morning sun sifted through the dingy window.

Shortly after dawn, I was in a hospital bed in Hamilton, N.J., cradling the snowy head of the woman who taught me how to ride a bike, roller skate and shuffle cards like a blackjack dealer.

If you had peeked into her room, you would have seen a frail, sick woman. That isn’t what I saw.

I saw a skinny brunette with wild curly hair, great legs and big smile. A woman who read poetry to me at night, who played the soundtrack to “Man of La Mancha” so often that she wore out the vinyl, who danced with me whenever “American Bandstand” was on TV.

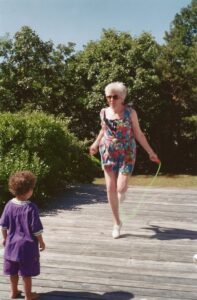

I saw the 30-something woman who taught me to jump rope, do handstands and bathe a cat.

I saw a young mother who walked to work every day and ignored the snickering in a small town full of stay-at-home moms. I saw a woman who never seemed to sleep. A woman who sewed most of my clothes and all of my Halloween costumes between loads of laundry after midnight.

I’ve written about my mother many times. Forgive me if you’ve heard some of this before.

She was a bank teller, my Brownie Troop leader and an amateur artist. She was a terrible cook, a teetotaler – until she had her first swig of Bailey’s Irish Cream – and the family handyman.

She hated doctors and loved games. She did not believe in letting kids win at checkers, Monopoly or pinochle. Trust me.

She was a voracious, indiscriminate reader. One day, she’d read Jane Austen. The next, Stephen King.

She was a voracious, indiscriminate reader. One day, she’d read Jane Austen. The next, Stephen King.

She was a high school dropout and during a prolonged period of stunning ignorance, I believed I was smarter than she was.

She loved me anyway.

She minded her own business, and she picked her battles with the skill of a seasoned field marshal.

She didn’t become apoplectic when I announced that I was quitting my job at a big-city newspaper, leaving my first husband and moving to Ireland to work as a freelance journalist. She later told me she’d thought I’d lost my mind, but never said a word at the time.

She rarely cried. Yet she wept when our Irish setter died, when they towed away her ancient Chrysler convertible, when I told her she was going to be a grandmother and when my father dropped dead of a heart attack just a few months before she found herself in that no-way-out hospital room.

On Sept. 16, 1998, I learned that even a bright orange “Do Not Resuscitate” bracelet is not enough to keep well-meaning medical staff from barging in with defibrillators when alarms sound at the nurses’ station.

It was left to me to wave them off, knowing that was what she wanted.

It was not what I wanted.

When they left, I slipped into bed with her. I told her she’d been a fabulous mom. I thanked her for all the laughs, the practical jokes, the tough love. I forgave her for those back-to-school Toni home perms that left me looking like a tumbleweed in class pictures.

I told her I was sorry I’d been such an ungrateful jerk so much of the time.

I promised I’d never forget her. And I haven’t.

It’s taken me 23 years to realize that being able to hold the woman who gave you life as she is leaving hers is a breathtaking gift.

Which is appropriate. Because that memorable day in September happens to be my birthday.