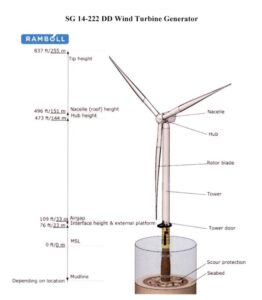

A schematic from the application for the proposed 14.7 megawatt turbines for the CVOW, with measurements. Click for larger view.

by Steve Haner

A similar article was published this morning by the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy.

Testimony filed by the State Corporation Commission staff on April 8 opened a slight possibility that the Commission could reject Dominion Energy Virginia’s proposed $10 billion Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project off Virginia Beach. It all depends on how the SCC decides to calculate the CVOW’s levelized cost of energy (LCOE), the dollar cost of every megawatt hour of electricity it produces plus the transmission costs.

When the 2020 General Assembly adopted the Virginia Clean Economy Act and related legislation, it set a cap on that key LCOE measure, which is used to compare the costs of various methods of making electricity.

If the utility failed to stay under the LCOE cap, the SCC would have the authority to reject the proposal as imprudent and unreasonable. If the project remains below the cap, legislators mandated approval by the SCC, despite any other doubts about its prudence and without considering less expensive alternatives.

The cap set was $125 per megawatt hour, after deducting the value of the very large tax credits granted for wind projects under federal law. In the application it filed late last year to build the facility, Dominion estimated the LCOE (after the tax credits) at about $83 per megawatt hour. But Katya Kuleshova of the SCC’s Division of Public Utility Regulation challenged several of the assumptions in her testimony and noted that if the assumptions prove wrong, that number rises substantially.

If a combination of the many assumptions – actual construction cost and schedule, energy output from the installed turbines, the assumed 30 years of steady operation – prove too optimistic, then the cost of energy can exceed that $125 per MWH target, she wrote. She also challenges Dominion’s failure to include $1.7 billion in future decommissioning costs, and questions whether at least some related energy-storage batteries should have been included.

It is Staff’s position, therefore, that the future energy storage investments should be included in the LCOE calculation of the CVOW Commercial Project, to the extent they are necessary to preserve the facility’s energy output and sell it at commercially optimal times.

Without enough storage, there may be times the turbines are pumping out electrons that are merely wasted. If that happens, she argued, none of those should be counted as useful output when calculating the “capacity factor” of the turbines, the percentage of the potential output which is achieved over time. Dominion claims the capacity factor will exceed 43% and the turbines will be operational 97% of the time. And it will be consistent over 30 years in a harsh marine environment. Reasonable?

Perhaps the largest hole she pokes in the LCOE, however, is based on the undisputed fact that with this project, Dominion will have far, far more generation than it needs for years to come. When drawing on this project, other viable power plants will be idled, “cannibalized,” in a term Kuleshova uses. That will impose costs that also should be considered in calculating the LCOE value it brings to the system.

System or incremental LCOE of the CVOW Project, calculated based on the Project’s net energy addition to the system and accounting for dispatch cost savings of the fossil-fueled generation units, would exceed $125/MWh in 2027 dollars in all scenarios tested by Staff. (Emphasis added.)

Unfortunately, most of the details of her analysis are based on data the utility has labeled as extremely sensitive or confidential, so her numbers are also either redacted or contained in sealed documents. The most important energy investment in Virginia’s history is being made with customers kept in the dark. Testimony from other witnesses is also riddled with redactions, and much of the May hearing will likely be behind closed doors.

Kuleshova also details the risks being imposed on Dominion’s 2.6 million Virginia ratepayers, again almost all of it hidden behind secrecy, with pages and pages of inked-over text.

Dominion proposes to build 176 turbines, each capable of generating 14.7 megawatts of electricity, 27 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach. It hopes to start construction next year and be fully operational for 2027. The case has already built up a massive file of documents and exhibits. Public comments are being taken here until May 16.

If approved, the costs for the project will begin to appear on customer bills this September in a new stand-alone rate adjustment clause (RAC). It starts small but ramps up quickly during the construction process and should peak in 2027 to just over $170 annually for a residential customer using 1,000 kilowatt hours in a month. This RAC will work differently, with customers credited for certain avoided costs. Thus, after plant operation begins the bill charge may start to decline.

Tracking earlier testimony from the Office of the Attorney General, the SCC staff goes into detail arguing that the claimed customer benefit (measured as net present value) is really negative, and substantially so. One key issue is how to account for the presumed “social cost of carbon,” which Dominion is treating like a specific cost imposed directly on its customers only. Kuleshova wrote:

Total customer benefits of the CVOW Commercial Project are lower than the Project’s cost if the social cost of carbon benefit is considered a separate societal benefit. Further, if the IFC (renewable energy certificate) price forecast is used as a source for REC proxy values, total customer benefits calculated by Staff are approximately half of the Project’s cost, and the Project’s (net present value) becomes approximately negative $1.6 billion.

The Attorney General’s expert set it even lower. Like the calculation of levelized cost of energy, however, there is no firm guideline or agreed-upon industry standard for what to include and what to exclude in the cost-benefit NPV formula. The two SCC judges (the 2022 Assembly failed to fill a vacancy) will decide.

Despite the finding that using different but still reasonable assumptions, the project might exceed its legislative cost target, the SCC staff did not recommend that the Commission reject the application. Neither did Attorney General Jason Miyares, the consumer’s representative at the table, despite his evidence that the project is unneeded for energy purposes, the customer benefit numbers are wrong, and lower cost approaches were ignored.

Miyares, the SCC staff, and other parties have asked the SCC to impose a cost cap on the project, and to find some way to put the cost of any construction delays or overruns back on the utility. There are also solar projects previously approved where if the energy production, as measured by the capacity factor, falls too low, consumers are protected from the downside cost.

Whether the Commission will impose such financial risk on the utility with a project of this size is a good question. Avoiding shareholder risk was the point of the 2020 legislation, although few legislators are sophisticated enough to recognize that and happily put their constituents at risk.