by James A. Bacon

Mirroring national trends, Virginia healthcare markets are severely out of whack. The main difference is that here in the Old Dominion, they’re even more out of whack than they are for the country as a whole. In 2018, total out-of-pocket medical insurance costs for Virginia employees (employee contribution to premiums + deductible) amounted to $8,143 — 10.2% more than the national average.

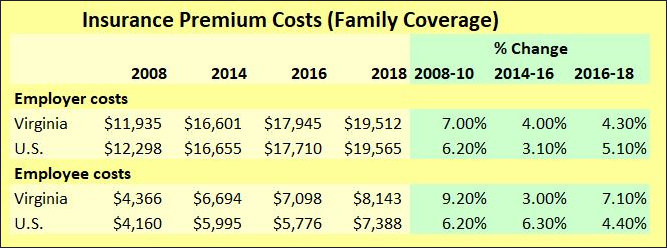

That’s on top of what employers pay. According to the latest data compiled by the Commonwealth Fund, employers on average contribute $6,635 for single coverage and $19, 512 for family coverage. Add up the employer and employee share, and the cost of family coverage is equivalent to about $13.30 per hour in earnings for a full-time employee.

These costs have rapidly outpaced the general cost of living. As a percentage of median income, out-of-pocket costs have increased from 6.9% of median income to 10.7%.

Out-of-control medical insurance costs constitute a crisis for Virginia’s middle class. While the public policy debate in Richmond has focused almost exclusively on how to extend insurance coverage to the poor and working poor in the form of Medicaid expansion and Obamacare, nothing more than lip service has been given to the crisis for people who pay their own way.

The issue of runaway medical costs provides a tremendous political opportunity for whomever who can seize it. On the national level, Democratic Party candidates like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders say the solution is “Medicare for All.” Unfortunately, their solutions would bankrupt the country without addressing underlying causes of medical cost inflation. President Trump is trying to bring more transparency to healthcare pricing in the hope that market forces will tame runaway costs. That’s a great idea, but it addresses only part of what ails the industry.

Virginia needs to act as well. Healthcare markets are primarily local in nature. Only a tiny percentage of people seek medical treatment outside their metropolitan area. State policies, state regulations, and local market forces drive health care costs, especially for the privately insured. Virginia lawmakers have totally and utterly failed to understand those cost drivers. Instead they have resorted to the simple-minded expedient of redistributing costs to politically favored constituencies — primarily from the middle class to the poor.

Here are some topics worth examining:

- Cost shifting. Penetrate opaque hospital accounting to reveal the extent to which privately insured patients subsidize Medicare and Medicaid patients. We need to know how much wealth transfer is occurring behind the veil.

- Hospital profits. While we’re delving into hospital finances, let’s examine the level of hospital profitability — with a special focus on nonprofit profits. How much are urban and suburban hospitals making? How much profit do they need to make to fulfill their tax-exempt purpose? What are they doing with their excess profits?

- Insurance carrier profits. Don’t let the insurance companies off the hook. How much competition is there in Virginia health insurance markets? What barriers exist to prevent competitors — especially entrepreneurs with innovative business models — from entering the marketplace? To what degree does the cartel structure of the medical insurance industry drive up premiums?

- Provider competition. How closed is Virginia’s healthcare industry to competition and innovation by entrepreneurs and out-of-state businesses? What barriers — such as Certificate of Public Need — exist to stifle market entry by competitors with lower-cost delivery models?

- Occupational guilds. How restrictive are Virginia’s health care occupational licensing laws? To what extent do those laws limit entry and drive up wages for select occupations? To what extent does the trade unionization of medical professions restrict the introduction of productivity-enhancing work arrangements?

In the 2018-19 election cycle, the health care sector donated nearly $11.5 million in campaign contributions, more than any other industry grouping but real estate and retail. The donor lists is a who’s who of special interest groups that regularly seek government favor:

Hospitals/health systems — $2,235,000

Physicians — $2,143,000

Dentists –$1,208,000

Nursing homes — $860,000

HMOs & medical plans — $804,000

Pharmaceuticals — $644,000

Medical supplies — $609,000

Optometrists — $533,000

Mental health — $458,000

Opthalmologists — $274,999

Pharmacists — $254,000

Anesthesiologists — $248,000

Healthcare consultants — $248,000

Nurses — $189,000

The list goes on. Each and every one of these special interests wants something from state government. Sometimes the big “ask” comes out in the open, as it did in the Medicaid expansion debate when billions of dollars were at stake. Most of the time, the issues are too obscure for the media to report and too complex for the average person to comprehend or care about.

In this massive, never-ending game of rent seeking, who represents the patients’ interests? No one. No one at all.

It’s about time that someone did.