by James C. Sherlock

The Business of Healthcare in Virginia

I have been asked many times about how freer markets in healthcare can coexist with our need to treat the poor. I will try to briefly cover some of the complexities of the answer to that question.

And I will show that of all of the government healthcare control systems, COPN is the only one that has proven to disproportionally hurt poor and minority populations by its decisions and their effects.

And it does so by design.

Government controls other than COPN

There is no such thing in the U.S. a totally free market in healthcare other than for providers of totally elective procedures such as elective cosmetic surgery. That is why the price for those procedures have been coming down for years.

All states license facilities and providers. That process subjects providers to state regulations and inspections. States have various laws and regulations that make non-discrimination and serving the poor a requirement for facility licensing.

The federal government also regulates providers. It offers them access to the huge Medicare and Medicaid populations, but subject to federal regulations and inspections if they wish to access those patients.

All general hospitals in Virginia accept Medicare and Medicaid because hospital inpatient payments from those programs are generally above costs, for some procedures far above costs. Outpatient procedure payments can also be profitable under those programs. But at a minimum, absent other patients to fill the appointments, Medicare and Medicaid patients help pay for the fixed costs of operating the facilities in the absence of other demand.

COPN

Virginia took market control to a new level in Virginia in 1973 with the implementation of the Certificate of Public Need (COPN) program. That program runs separately from the state licensing process and governs building, expanding and equipping medical facilities.

COPN was passed in the General Assembly when it was still led by the Democrats that led Massive resistance. COPN was born as the historically Black hospitals in Virginia faded from the scene following integration of the white hospitals.

The owners of those hospitals convinced the General Assembly that they needed protection from outsiders, new players who would build indiscriminately.

The official reason offered for COPN was that these out-of-state brigands would drive prices up for the new Medicare program, which at that time offered cost-plus reimbursements.

That of course was the excuse, not the reason, as was proven when the funding formula for Medicare changed and COPN endured. COPN remains classic rent-seeking: entrenched interests asking the government for protection from competition. It worked beyond their wildest dreams.

Anticompetitive and pro-monopoly are two different levels of controls. COPN was designed to be anticompetitive to the extent it let in no providers from outside Virginia. It could have done that and still treated incumbents equally and tried to maintain competition among them.

The history of COPN in Virginia, however, is pro-monopoly. The political appointees that have run the program, Virginia’s Health Commissioners with sole authority to approve or reject applications, have run it by dividing up the state into dukedoms in which a single provider system controls each market. The only exception is the Richmond area, where most state government officials live.

I wrote yesterday that the Health Commissioners have overridden regularly the recommendations of their professional staff to hand out approvals to favored monopolies and denied them to their competitors.

That is in-your-face public corruption that has never been challenged. It is unfortunately the Virginia way.

So is COPN racist? Let’s examine the case.

COPN has stipulations for treating the poor, but not for the physical location of new facilities.

COPN runs on a system in which a proposal for a new hospital where patient growth does not signify “need” cannot propose inpatient beds or equipment for a new facility without “turning in” beds and equipment already licensed to that provider in the same geographic region of the new hospital.

In areas with stagnant growth, COPN not only allows, but demands the reduction and sometimes allows the closing of existing facilities in order to “transfer” the beds to new ones.

But how those rules are applied are utterly dependent on the single final decision authority, the Health Commissioner.

Sometimes the Health Commissioner has rejected a bid to transfer beds from, say, DePaul, with more beds than its patient loads required, to new facilities because he alone determined they were “needed” at the old location. That was a primary reason cited for the wholesale rejection of Bon Secours COPN applications in 2008, even though the Bon Secours bid specified DePaul was to remain open and be modernized but with fewer beds in its current location.

In other decisions, if the applicant is a favored monopoly like Sentara, the Health Commissioner permits the shutdown of an entire hospital like Bayside serving adjacent minorities to transfer the beds new facilities. Unlike the decision for DePaul, Bayside’s disproportionately poor and minority patients were judged not to “need” the beds. “They” could travel to other hospitals according to an interview with a Sentara executive at the time.

The curious thing was that those two decisions — Sentara got everything it asked for and DePaul was denied everything — were released on the same day in 2008 by the same person.

The effects of those twin decisions were the immediate shutdown of Bayside and the eventual shutdown of DePaul. Turns out that COPN cannot keep a hospital from going broke. Those two hospitals served poorer adjacent populations than any other hospitals in South Hampton Roads except Bon Secours Maryview in Portsmouth. Now there are no beds at either the DePaul or Bayside. Now DePaul’s “they” can travel to other hospitals as well.

I honestly do not think race has anything to do with the Sentara’s business model. But I am sure that profit does. Not a bad thing, profit, a necessary thing actually, but if a company is going to declare itself a not-for-profit public charity and avoid hundreds of millions annually in taxes, we citizens would like it to act like a charity in its business decisions and well as in its donations and support of the health of the population.

Giving money to the Virginia Symphony is a nice thing to do, but it is not the same as making sure poor people are provided hospital services where they live.

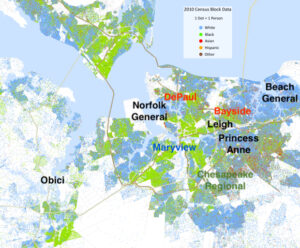

See the demographic map below on which I have superimposed the hospitals here.

South Hampton Roads Hospitals – Black Sentara, Red closed, Blue Bon Secours, Green Chesapeake Regional

The Sentara hospitals in the area approved under COPN, Virginia Beach General and Princess Anne, are located farther from minority population centers than the legacy regional hospitals. I referred to that in an earlier post as the “Nordstrom Rule”.

What can be done?

Health care will never be a fully free market, and should not be, but it operates more freely in states without certificate of need laws. Competition remains a good thing. Providers who must compete on the basis of quality or cost or both will provide better, more affordable services.

Either government or private attorneys will have to go after the COPN-created monopolies. The fact that they were created by state action makes the actions harder, but it can be done under existing state and federal antitrust laws based on anti-competitive activities of those regional giants.

As for COPN, it was designed to be fundamentally anti-competitive to protect incumbents. It was turned without any authorization to the purpose of regional monopolization. The system has proven to be publicly and unapologetically corrupt. Both monopolization and anti-poor outcomes have been byproducts of the COPN process and single person decision authority.

Either abolish COPN or turn it over to an independent regulatory agency on the Maryland example. If it is to be retained, the General Assembly should demand it ensure improved competition and that COPN does not provide cover for outcomes that disadvantage the poor in favor of corporate profits.

If Bon Secours or Sentara or any other market participant want to build a new hospital, they should build a new hospital. Just don’t make them shut one down to build a new one. Most will pick their poorest performing facility every time.

And don’t try to second guess applicant financial positions, as the Health Commissioner clearly did in the 2008 Bon Secours decision. Certainly make sure they can support the plan they offer, but Bon Secours also told him it needed permission for its new investments to support DePaul and Maryview.

The Commissioner had a different idea. He turned them down. Heck of a day’s work:

- DePaul is closed;

- Bayside is closed;

- Lots of poor people are further away from a hospital;

- Bon Secours and Maryview are weakened.

- Sentara’s Norfolk/Virginia Beach hospital monopoly is complete.

Probably a coincidence.