by James A. Bacon

One day some 60 years ago, I caught the flu. My mother, who believed that “sunlight and fresh air” cured many ills, deposited me in a chaise lounge in the side yard, threw a blanket over my lap, and let me soak up the great outdoors. I have no idea if the unorthodox treatment accelerated my recovery, but as I grew older, I came to regard faith in the curative powers of “fresh air” as no more scientifically founded than warding off illness through herbal remedies or appeasing ancestral spirits.

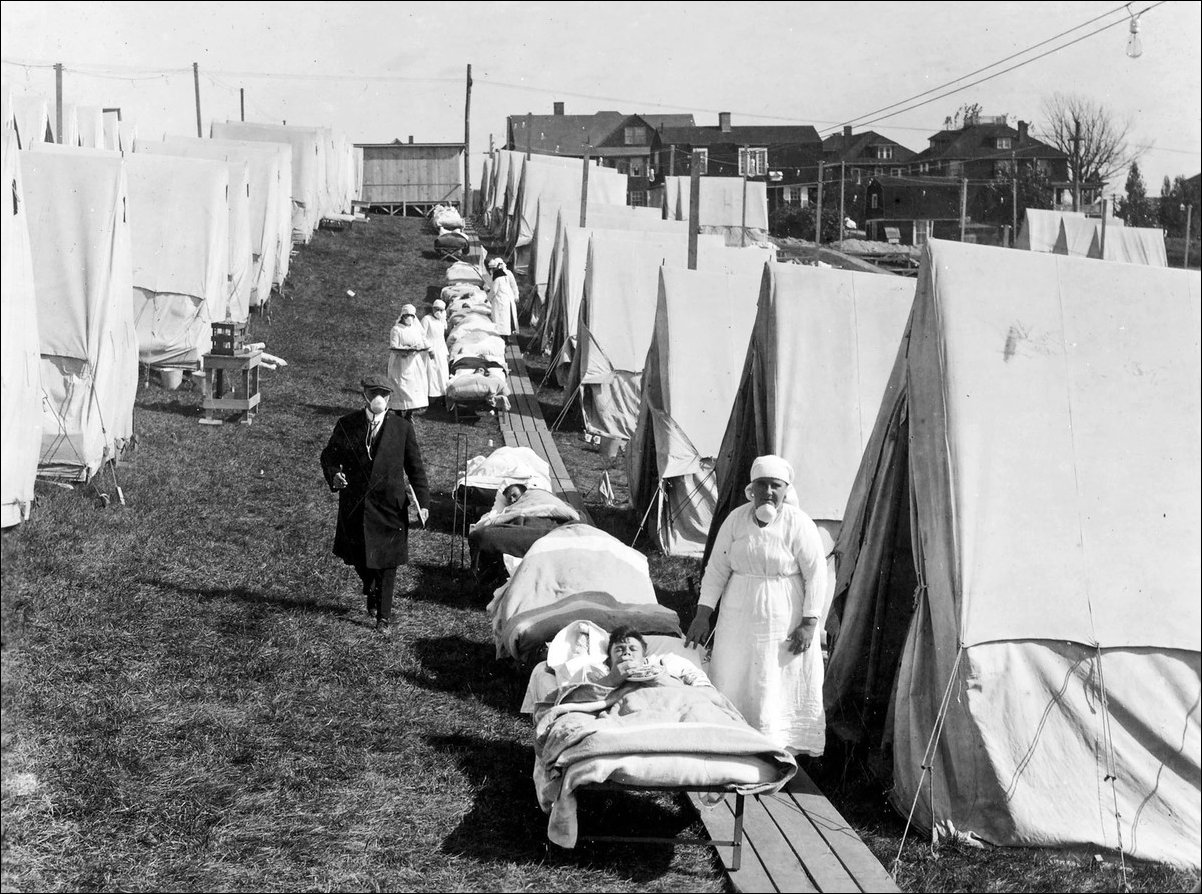

Now an article in Medium.com by Richard Hobday has me thinking that my mom, despite her ignorance of all things scientific, might have known more than I did. In studying the history of the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918, Hobday found that placing patients outdoors reduced their mortality rate.

Put simply, medics found that severely ill flu patients nursed outdoors recovered better than those treated indoors. A combination of fresh air and sunlight seems to have prevented deaths among patients and infections among medical staff. There is scientific support for this. Research shows that outdoor air is a natural disinfectant. Fresh air can kill the flu virus and other harmful germs. Equally, sunlight is germicidal and there is now evidence it can kill the flu virus.

In all likelihood, my mom’s faith in fresh and and sunlight reflected folk wisdom — lost in the institutionalization of health care — stemming from the experience of 1918. That folk wisdom is worth taking into account as Virginians consider how to cope with the COVID-19 virus, which, though not a strain of the flu, bears strong similarities to it.

In research published in 2018 by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), David Slusky and Richard Zeckhauser analyzed the relationship between the spread of influenza and the availability of sunlight. Citing literature suggesting that Vitamin D supplementation protects against acute respiratory tract infection, they correlated the average length of sunlight in the 50 states during the month of September with the incidence of influenza.

The human body uses sunlight to produce Vitamin D. Although the body can absorb the vitamin through pills and food sources such as fortified milk, they write, passive sunlight exposure is a more effective source of vitamin D. (I have read other studies suggesting that sunlight also might be an important catalyst for other metabolic processes that can boost the body’s natural immunological defense. The science is only dimly understood.)

Slusky’s and Zeckhauser’s conclusion:

We find that sunlight strongly protects against influenza. This relationship is driven by sunlight in late summer and early fall, when there are sufficient quantities of both sunlight and influenza activity. A 10% increase in relative sunlight decreases the influenza index in September or October by 0.8 points on a 10-point scale.

There is an important lesson here, though somewhat speculative in nature: As Virginia enters spring and the days of sunlight lengthen, we could find that our collective resistance to the COVID-19 improves — as long as we spend more time outside in the fresh air and sunlight.

Certainly we need to maintain social distancing. But that doesn’t mean we have to coop ourselves in our houses, squinting the entire time at our iPhones and computer screens. We should make a point of spending time outdoors, whether tending gardens, taking long strolls through the neighborhood, or (when it gets a bit warmer) basking in the sun. I dare say it’s perfectly fine to interact with friends and neighbors we encounter on the sidewalk — just don’t hug or shake hands!

I, for one, intend to follow my own advice. Feel free to mock me if a bout of COVID-19 sends me to the intensive care ward!