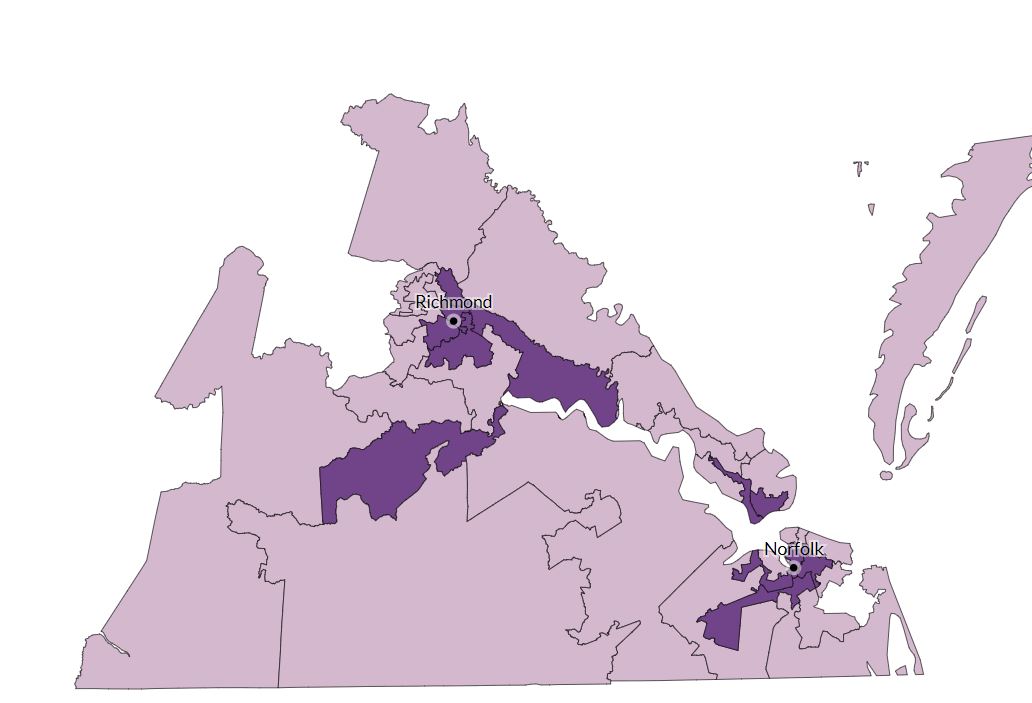

VPAP map showing 11 districts rejected by the court this week, and others likely to change along with them. An interactive version is linked.

The predominant consideration in a legislator’s mind in any effort to draw legislative districts is first, will I get re-elected and second, will enough of my friends get elected or re-elected so we can form a gang and control this place? The third consideration is can we get this plan signed by the governor and (in Virginia) get it approved by the federal guardians of the Voting Rights Act?

Compactness, contiguity, community of interest – a strong stand in favor of those works well in campaign speeches. Close the doors and turn on the mapping software, however, and they’re back to numbers one, two and three. The third consideration, federal approval, may now leap to number one.

No piece of legislation has been more important to the rise of the Republican Party in the Old South than the Voting Rights Act, because with the creation of every “minority-majority district” the surrounding districts also change demographically. The South’s (and not just the South, by the way) racist efforts to suppress African-American registration and to draw districts that cracked, stacked and packed them to further dilute their political power brought a just and powerful retribution. The impact on black representation was strong and immediate, but so were the corollary benefits for Republicans.

In 1991 the Republicans were the minority in the Virginia House and were victims of a gerrymander. The only effective challenge put up was a GOP complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice involving the House seat then held by the late C. Hardaway Marks of Hopewell, parts of which could have been used to create a new minority-majority district next door. It was so ordered and Marks’ seat went red.

The 1991 plans on both sides created substantially more black majority districts and were the first legislative plans to maximize Section 5 compliance as then interpreted. Within a decade the GOP controlled both chambers. There were many reasons but the Voting Rights Act played a role.

Live by the sword, die by the sword. Judicial interpretation of Section 5 of that federal law is changing. A couple of years ago a federal court redrew Virginia’s congressional seats, effectively replacing Republican Randy Forbes with Democrat Donald McEachin. Now comes a 2-1 U.S. District Court ruling that as many as 33 of 100 House of Delegates seats need to be redrafted because the Republican mapmakers used a fixed 55 percent minimum for the black voting age population (BVAP) in 11 specific districts held by Democrats. The one-seat GOP majority in the House is now even more tenuous. (VPAP has done a marvelous map and the interactive version is here.)

The opinion and the dissent run to 188 pages, but the parts of the majority decision I read boil down to these sentences: “The state has sorted voters into districts based on the color of their skin” and speaking of the consultant used by the GOP: “Insofar as he sought to obtain partisan political advantage by splitting (precincts) in particular ways, he did so by relying on race as a proxy for political preference.”

Given the black voting patterns these days, which may be even more set in stone now than 40 years ago, it is hard not to see that as proxy. What has changed in 40 years is white voting patterns.

Since the initial passage of the Voting Rights Act, Virginia has elected one African-American governor, has twice elected an African-American lieutenant governor, and has twice voted for an African-American for president. The justification for the Voting Rights Act Section 5 requirements in the first place was a strong pattern of racial voting among white voters, strong enough that no black candidate stood a chance unless the district was tailored for his or her success. That is not today’s Virginia.

The ground was already shaky under that foundation by 1991, with Governor Douglas Wilder on the Third Floor and then-state Senator Bobby Scott of Newport News winning in a 65 percent white district. Neither Scott nor Wilder passed on the chance to demand 1991 plans with more minority-majority districts, however, and Republicans in the Senate cooperated with that desire and negotiated a map equally beneficial to them.

Reading the new district court majority opinion, the presumption that African-American candidates need that demographic boost still binds the action of the legislature, and the plan adopted certainly provided it. The problem was uniform reliance on that 55 percent minimum target, which was chosen after careful analysis of the voting patterns in just one legislative district – the rural Southside district held by Del. Roslyn Tyler of Jarrett.

The court accepted the arguments of the plaintiffs that every district needed its own analysis, and many could produce a district open to a black candidate winning with far less than a 55 percent BVAP. It noted that the Tyler district’s results were skewed by the presence of large non-voting prison populations, and by the fiercest pattern in the state of racial pattern voting by its white citizens. The mandate to the General Assembly is go back and reevaluate all 11 other districts individually, change their lines and those of surrounding districts, and get it done by Halloween.

What wonderful timing for Democrats defending their U.S. Senate seat against a GOP challenger who might have interesting comments to make on the role of federal courts and the wisdom of the Voting Rights Act. That mandate and deadline will be appealed but now that is complicated by the coming period of a 4-4 Supreme Court until a new justice is approved and sworn.

Odds are very good this ruling will stand and the General Assembly will have a new House map for the 2019 election containing several Republican-held districts with higher numbers of African-American voters. Permissible “proxy” or not, the partisan impact is predictable.