Enrollment trend at Reynolds Community College.

by James A. Bacon

Last month Governor Ralph Northam announced a plan to spend $145 million to make community college tuition-free for low- and middle-income students pursuing jobs in high-demand fields. As justification for this massive entitlement expansion, he cited numbers from Reynolds Community College showing that students who dropped out before completing their degrees “usually had earned a 3.1 grade point average when they left school.” The reason they left, he asserted, was not an inability to keep up academically but a lack of money.

In this post, I questioned the numbers. I didn’t dispute them, but I wanted to know more about where they came from and what caveats might apply before committing to a $145 million spending program. I promised to ask J. Sarge (as we Richmond old-timers still refer to the college) where the 3.1 GPA number came from and report back.

So, I have obtained the information, and now I’m reporting back. Bottom line: Northam got part of the story right, but he drew totally unwarranted conclusions from the data. The justification for the $145 million initiative has no empirical foundation basis.

Let’s see what the Governor said when announcing the program in his State of the Commonwealth speech, and then let’s see what the data is to support it.

At Reynolds Community College here in Richmond, a majority of students are people of color. The college looked at “retention rates” — who starts a degree program and then goes on to complete it. They identified students who started one academic year and didn’t come back the next. They asked why didn’t these students come back.

The answer is really important. The facts showed it was not academics that kept them from coming back. In fact, these students usually had earned a 3.1 grade point average when they left school.

These students enrolled in a degree program — trying to get a skill, so they can get a job, and provide for the people they love. They set a goal. They worked hard. They performed well, but they dropped out. Why? They left because life got in the way. The car broke down. Or the baby got sick. Or they lost their job. Just trying to get ahead. And then life hits you.

I’ve highlighted the key links in Northam’s logic chain: (1) Reynolds asked why students dropped out before completing their degrees; (2) students who left “usually” had earned a 3.1 grade point average, which shows that academics did not keep kept them from returning; and (3) they left “because life got in the way.”

“They asked why didn’t these students come back.” No, actually, they didn’t. The Reynolds administration compiled a list of all the students who had enrolled at the community college in the fall of 2018 to see what their attendance status was one year later, in the fall of 2019, and it did examine the grade point averages of those who stayed and those who returned. However, the administration did not query students why they left, nor did it undertake a comprehensive statistical analysis of why they might have left.

“The data provided was internal data the college regularly collects and was used by the College President for her Convocation presentation,” J. Sarge spokesman Joseph J. Schilling told me.

In that presentation, which you can view here, President Paula P. Pando did focus on the issue of student retention, breaking down the retention rates of students by full-time/part-time status and race/ethnicity. One of her data points was the fact that both part-time and full-time students had an average GPA of 3.1. She then outlined the college’s strategic priorities: (1) to invest in faculty and staff knowledge and expertise to help students persist and complete; (2) simplify enrollment; (3) provide support services that “meet the needs of our diverse student population”; and (4) connect the college’s curriculum to the labor market.

Presentation slides did highlight the existence of food pantries on all three J. Sarge campuses, and alluded to ALICE (asset limited, income constrained, employed) students. However, there was no empirical analysis connecting student finances to the high dropout rate.

“The facts showed it was not academics that kept them from coming back. In fact, these students usually had earned a 3.1 grade point average when they left school.” Nah, that’s not right. Here’s what the “facts” showed: Full-time students who had enrolled in 2019 were more likely to return than part-time students, and Asians and Hispanics were more likely to graduate with degrees than whites and African-Americans. While the J. Sarge presentation provided data on who was graduating and dropping out, it offered no explanation of why students failed to graduate. In theory, J. Sarge could have correlated retention and dropout status with students’ financial status, as measured by their reliance upon grants and loans, but that’s not what it did.

Further, while the average full- and part-time student’s GPA was 3.1, the Governor was not quite accurate to say that the students “usually” had earned a 3.1 GPA when they left school.

I compiled the pie chart above from data supplied by J. Sarge in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. The chart breaks down the nearly 4,200 non-returning students by GPA. Forty percent of the drop-outs did have a GPA of 3.1 or better. It is fair to say, however, that the 10% of dropouts whose GPAs averaged less than 1.0 probably did leave school for academic reasons.

The Governor would have been safe to say say that a large percentage of drop-outs had a 3.1 GPA or better, and that those students did not leave for academic reasons.

“They dropped out. Why? They left because life got in the way.” Here is where the governor makes a stupefying leap in logic. If students with 3.1 or better GPAs dropped out, the governor surmises, the reason is that “life got in the way” — that they encountered financial difficulties, and that, therefore, they needed more state financial aid. However, there is at least one other major reason why students might have dropped out — because they got jobs!

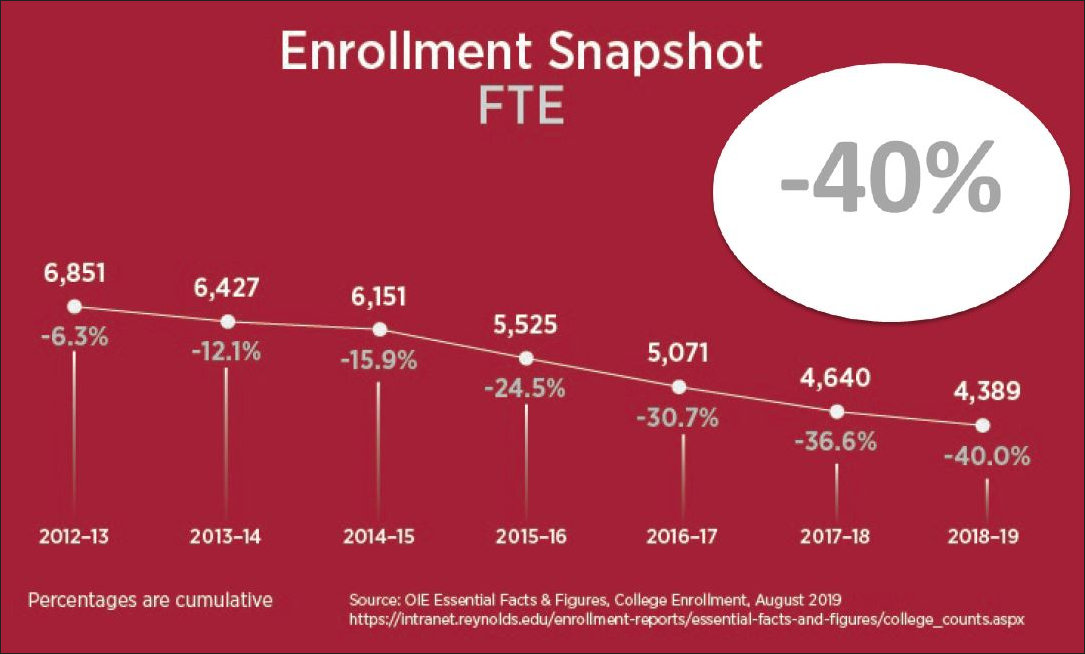

Overall enrollment has declined 40% at J. Sarge since 2012-12, as seen atop this post in a chart taken from Pando’s Convocation presentation. It is widely recognized that when unemployment is high, workers are more likely to enroll in community college to burnish their workforce credentials, and that when unemployment is low, they are more likely to take jobs. The unemployment rate in the Richmond metropolitan area in December 2019 was about 2.8%. In other words, almost everyone who wants a job can find a job. Fewer people see the point in enrolling in community college, and it is likely that many college students dropped after a year out not because of financial hardship but because they found remunerative employment.

Is that to say that nobody dropping out of J. Sarge experienced financial hardship? No. We have no way of knowing from the data how many left because of job opportunities and how many dropped out because “life got in the way.” But the burden of proof rests on Governor Northam. He’s the one claiming that an educational access crisis exists, and he’s the one proposing a $145 million entitlement expansion.