Tomorrow the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) will release the first public school accreditation ratings calculated according to the 2017 Standards of Accreditation. The new standards are designed to measure how well schools are educating Virginia’s school children, giving credit to schools that are showing progress even if they fall short of the standards.

Tomorrow the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) will release the first public school accreditation ratings calculated according to the 2017 Standards of Accreditation. The new standards are designed to measure how well schools are educating Virginia’s school children, giving credit to schools that are showing progress even if they fall short of the standards.

VDOE has a tough job. On the one hand, educators want to set high standards of achievement so Virginia students can engage successfully in a highly competitive global economy. On the other, rule writers want to acknowledge the challenges faced by schools with disproportionately large numbers of “at risk” students — those with disabilities, from lower-income families, or who speak English as a second language. The new accreditation standards cut low-achievement schools some slack if they manage to improve performance year to year.

As VDOE summed up the new approach in a press release issued in anticipation of the accreditation report tomorrow:

The new state accreditation standards are designed to promote continuous achievement in all schools, close achievement gaps and expand accountability beyond overall performance on Standards of Learning tests. These new standards also recognize the academic growth of students making significant annual progress toward meeting grade-level expectations in English and mathematics.

You can read here a detailed explanation of what goes into the accreditation standards. Schools will be evaluated according to three broad sets of criteria:

- Overall student achievement based on Standards of Learning (SOL) pass rates for English, math, and science in elementary and middle schools, and on other criteria in high school.

- Achievement gaps based on differences in average scores between “student groups.” The groups are not spelled out explicitly, but presumably are racial/ethnic groups or groups defined as “disadvantaged,” disabled, or ESL (English as a Second Language).

- Student engagement metrics such as dropout rates, absenteeism, and graduation and completion rates.

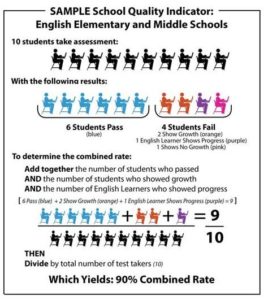

VDOE provides an illustration (reproduced above) of how this might work for a sample middle school. Let’s say 10 students take the SOLs and only six students pass. But if two of the failing students showed “growth,” and one English Learner showed “progress,” the school would be given a “combined rate” of 90%.

The goal is admirable: to reward schools that show achievement gains even if the average pass rates fall short of desired standards. It makes no sense to shame teachers and administrators of poorly performing schools if they’re showing signs of engineering a turn-around. The danger of this approach, however, as amply demonstrated by SOL cheating scandals in recent years, is that teachers and administrators may be tempted to game show progress by manipulating the metrics.

That danger appears to be most evident in the high school “student engagement” metrics. One way school districts have combated high drop-out rates is by ramping up their anti-truancy programs. But it’s one thing to get kids back onto the school grounds, and another to get them into the classroom. At some schools, teachers literally patrol the grounds to get kids back inside. And even if kids are corralled into classrooms, there is no guarantee that they are learning anything. Indeed, to the extent that disruptive kids are coaxed back into classrooms, they may degrade the learning of others. In the end, evaluating schools based on drop-out metrics creates tremendous incentives to give kids so-called social promotions. Many students now attending graduation ceremonies receive “certificates of attendance” — improving a high school’s “completion” metrics but degrading the value of the high school credential and tarnishing the accomplishment of students who, despite the odds, earned a diploma.

There is another danger in the high school evaluations — how to show students’ progress in the absence of SOL tests, the last set of which occurs in the 8th grade. The VDOE summary mentions “assessments” for English, math and other subjects but does not say what they are. The following comments here are based upon a fragmentary understanding of how the system works, thus they are subject to correction. I bring up the topic in the hope that readers will fill in any gaps.

In Henrico County, high school teachers compile SGMs or Student Growth Measures, for each of their students. While students may fall short of standardized assessments, the idea is to document that they have at least shown “growth” in their understanding of a subject through the school year. Teachers are evaluated by the number and percentage of their students who show growth. The potential for sanctions creates incentives for teachers to fudge the evaluations — counting even miniscule signs of learning as “growth” — in order to give administrators what they want. The SGMs do not indicate mastery of a subject, but they allow administrators to say their students are making progress.

What happens in Henrico County may or may not be representative of what occurs in other Virginia school districts. But the temptation for teachers and administrators to fudge statistics is universal. VDOE can update its methodology for accrediting schools, and the department can try earnestly to safeguard its metrics against cheating and manipulation. But when schools are driven to graduate kids who have no desire to learn, and administrators are compelled to adopt restorative-justice disciplinary methods, and VDOE tightens its strait-jacket of rules and reports — in sum, when teachers and principals are asked to do the impossible — don’t be surprised if school statistics and accreditation reports become increasingly disconnected from reality.