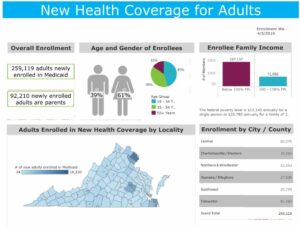

Expansion tracking on the Virginia DMAS website. Click to expand, web version is here.

Virginia makes is easy to track the growth of Medicaid enrollment since the decision a year ago to expand coverage but tracking the tax dollars behind the scenes is another matter.

The new enrollment expansion dashboard on the Department of Medical Assistance Services website is updated every couple of weeks, with the April 4 report showing just under 260,000 people added to the program since late last year. The City of Salem has added the fewest, only 34 new recipients, while Fairfax County has added the most at 18,220. The advertised goal for expansion was 400,000 persons, so probably there are more to come.

The state share of the cost to serve them is being paid by a provider tax on the revenue of large private hospitals in Virginia, which also started being paid late last year. There are two provider taxes, in effect taxes on gross receipts, one to pay for expanded enrollment and the other to pay for improved payments to the service providers.

The normal dashboard for tracking state tax receipts is the monthly report provided to the public by the Secretary of Finance, and you will not find the Medicaid provider assessments totaled or mentioned there. Yet another update came out April 11, with nine months of the fiscal year completed.

You won’t find the provider fees tracked among the ten pages in the standard release, which cover the general fund taxes and fees, the various transportation-related taxes and fees, the lottery’s sales and transfers, interest on state investments and the revenue stabilization (a.k.a. rainy day) fund.

It is time add a page to that monthly report covering the Medicaid program, providing a focus on the details of income from the various sources. It is just as important now as the other topics covered in the report, and recent forecasting errors show it poses the most risk. The report could look like the existing running summary for transportation programs, which combines several revenue streams, including federal.

Such a report may already exist and simply isn’t being published. If it were readily available, comparing fiscal years 2018, 2019 and 2020 would provide a good feel for the growth in revenue and expenses authorized by the 2018 General Assembly.

The General Assembly voted to create the new provider taxes, which the industry supported, with language in the state budget, not direct legislation. The budget language included an estimated two-year $376 million revenue total for only one of the provisions, the smaller of the taxes related to the coverage expansion.

On request, the Secretary of Finance’s staff provided the two-year revenue estimates for the second and larger levy, $486 million over two years, to help pay for the higher provider payments. It is unchanged from charts used in pre-session meetings and reported by Bacon’s Rebellion late last year. A query to the Senate Finance Committee staff last month also elicited the combined estimate for fiscal year 2021, $860 million. That’s getting to be real money.

How much has actually been collected month to month is only available to anybody with access to the state’s internal accounting systems and knowledge of the account codes, who compiles and publishes it. That of course would not be most people.

This method of taxing Medicaid providers to draw down matching money from the federal government, with the combined dollars then paid back to the providers, goes on in 49 states at last count. Many tax a wide range of providers, not just hospitals. Virginia is likely to expand the practice beyond hospitals eventually.

The amended state budget projects that over the two years ending July 2020, Medicaid services in Virginia will cost more than $28 billion – from state general funds, federal funds and now these new hospital taxes, presumably classified as a non-general fund (same as college tuition). The new budget proposed next December will likely push the two-year total well past $30 billion, with almost $2 billion of it coming from those two hospital taxes.

Every budget decision process now starts with the question, how much is left after we fund Medicaid? It is time to bring the state’s largest activity and this growing revenue stream into full view with monthly updates.