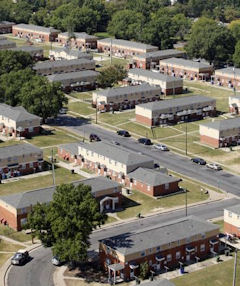

The Creighton Court housing project in the east end of Richmond. The city never built high-rise projects comparable to Chicago’s infamous Cabrini-Green towers but social disintegration occurred anyway.

by James A. Bacon

The City of Richmond is embarking upon the boldest experiment in a generation to tackle entrenched, multi-generational poverty in the Richmond region. With the hoped-for assistance of $30 million in Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds, city officials are planning to blaze a path of mixed-income re-development through the city’s east end, one of the largest concentrations of urban poverty in the state.

The East End is ringed by four public housing projects, its old commercial corridors are decaying, and its neighborhoods of single-family dwellings are pockmarked with vacant lots and uninhabitable buildings. In the thinking of Mayor Dwight C. Jones, the problems of poverty are so intractable because they are so concentrated. As Zachary Reid with the Times-Dispatch quoted Jones in a Sunday article:

“A lot of the negative things that are happening in Richmond, they’re happening because we have this concentration of poverty.” Here’s how Reid describes the vision for busting up the pockets of poverty through some $200 million in public and private investment:

Blocks and blocks of dreary public housing will give way to more livable communities: houses, townhomes and apartments in nice rows: walkable, livable, appealing in street grids typical of a city, not the dead-end cul-de-sac world of today’s Creighton Court. Kind of like the Fan, only new: a place where the young and old, the rich and the poor, can mostly happily coexist. Jobs, retail, transportation, anything else people need to live happy, hopeful lives, will be right there where the residents can get it. “The importance of decentralizing poverty is not accepting the premise that people are at their best or have the opportunity for success when there’s only one strata of society living together,” Jones said.

So begins another liberal social-engineering effort to un-do the damage created by a previous generation of liberals social engineering. At the dawn of the do-gooder era, when the New Deal began tearing down slums and erecting public housing, liberals acted on the conviction that slums created poor people, not the other way around. Provide clean, modern housing and people would take on the bourgeois habits of thrift, sobriety and self-discipline. Needless to say, it didn’t work out that way. Putting people in brand-new public housing did little to change their behavior. To the contrary, the projects only accentuated the “social disorganization” of the poor. Then, as the Great Society added layer upon layer of “anti-poverty” programs — “poverty-perpetuation” programs might be a more accurate descriptor — out-of-wedlock births, substance abuse and crime and violence became even more endemic. But liberals didn’t see anti-poverty programs as the problem. They decided that the great sin of past housing policy was concentrating poverty. This time, they’ll get it right.

De-concentrating poverty is the new mantra. Jones does deserve credit for putting a new wrinkle on his anti-poverty initiative. He wants to change the culture of poverty — something that past federal programs have been habitually unable to accomplish. Recalling how he grew up in a mixed-income neighborhood, Jones said, “We had something to aspire to. We recognized there was more, there was a model of success, not a model of failure. People were getting up and going to work. That became a way of life for us.”

When we rebuild these areas, we’re also rebuilding lives and culture. If you’re going to live in these new places, you’re going to work. The people who are going to be moved out and move in have got to go through some changing, some acculturation, some orientation so that they’ll be ready for the new housing that we’re getting ready to put them in.

Exactly what cultural attributes does Jones envision changing? And what sanctions will he apply to those who do not comply? The programmatic aspects are pretty vague. Still, Jones’ call for a return to 1930s-era, New Deal thinking when people still were expected to work is a step forward. It will be interesting to see how Jones’ thinking plays out in practice.

Another new wrinkle is that we need a different form of urban design. Call it New Urbanism meets HUD. A key insight of the New Urbanists is that the proper design can put “eyes on the street” and create “defensible space,” in which neighborhood residents take control of the public space rather than yielding it to criminals. There might be something to this, but I suspect design considerations are a relatively minor influence. Still, it’s worth a try. If you’re going to re-design communities, it can’t hurt to design them with the goal of fostering community interaction and crime prevention.

Here’s the really big problem, as we know from innumerable experiments elsewhere to de-concentrate poverty. Middle-class people don’t want to live in proximity to poor people. Upwardly mobile poor and working class people want to escape poor people. Indeed, they are willing to pay higher rents and mortgages to do so. It’s not a race thing. This applies to middle-class blacks as well as whites. Poor families are less likely to maintain their property, more likely to engage in substance abuse, more likely to engage in violence, and more likely to be loud and disorderly. (That’s not to say that all poor people suffer from social disintegration — they’re just far more likely to. Poor people who graduate from high school, don’t have out-of-wedlock births and don’t engage in substance abuse tend not to stay poor for long.)

There is one segment of the middle class that is willing to tolerate the social disorganization of the poor — gentrifiers. But they tend not to move into brand new buildings. They are looking for aging, run-down buildings where they can put in some sweat equity and build up their net worth. Whether the gentrifiers can be drawn to the East End’s new, mixed-income corridor is a big question.

Clearly, the policy mix we’re pursuing now is not working. Whether this new approach does better, we won’t know until it plays out. Personally, I think we’re attacking the cosmetics of poverty, not the root causes.

Update: Jones’ anti-poverty initiative has been profiled by the New York Times.