This story was originally published in Henrico Monthly.

Willow Lawn returned to its roots. Cloverleaf was torn down. So what will become of Regency Square?

Willow Lawn returned to its roots. Cloverleaf was torn down. So what will become of Regency Square?

By James A. Bacon

As a teenager growing up in rural Hanover County, Andrew Moore remembers Regency Square Mall in Henrico as the place to go. He played the trumpet in Christmas concerts there with his junior high school band. Later, equipped with a newly minted driver’s license and the family car, he hung out with friends, circling the two-level shopping promenade and sampling the edgy and exotic wares of places like Spencer’s Gifts. “In a very real sense, Regency was the center of a regional community,” Moore recalls. “For a teenager, it was the cool place to go on a Friday night.”

Today Moore lives in the Westham neighborhood in Henrico, a mere five-minute drive from the mall. He’s been to Sears a couple of times to buy some Craftsman tools; otherwise he doesn’t recall visiting Regency Square in the last seven or eight years. “I have no reason to go there. There’s nothing there that I need,” he says. With all the congestion on Parham Road, he adds: “Frankly, it’s a pain in the butt to get there.”

And that’s a shame, he says. If the southwest corner of the county has a natural civic center, it would be Regency Square. But the mall has been supplanted over the past decade as a retail destination by newer, open-air shopping centers such as Stony Point Fashion Park south of the James River and the super-successful Short Pump Town Center off Interstate 64. Retail sales at Regency Square reportedly have declined by two-thirds.

By 2012 the mall was faring so poorly and bogged down with so much debt that its owner, Taubman Centers Inc., turned it over to its lenders. The lender group has kept the mall open, but the complex continued bleeding tenants. Now the banks are attempting to sell the property at a price said to be at a discount to its $23.5 million assessed value. In late January, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that two local real estate companies, Chesterfield-based Rebkee Co. and Thalhimer Realty Partners Inc., were in negotiations to buy the mall by the end of January. Further details weren’t available by Henrico Monthly’s presstime.

So what comes next? Will a new buyer continue to operate the mall on the cheap? Will another developer repurpose the mall, perhaps bringing in a medical facility or an educational center, to generate traffic and anchor the stores? Does the 48-acre property, if redeveloped, have a future as a walkable “town center” that sparks the transformation of the neighborhoods and shopping centers around it?

Andrew Moore, president of the Partnership for Smarter Growth, says Regency Square has struggled to remain relevant as a mall. He envisions the property being redeveloped into a walkable shopping district such as Carytown.

Andrew Moore, president of the Partnership for Smarter Growth, says Regency Square has struggled to remain relevant as a mall. He envisions the property being redeveloped into a walkable shopping district such as Carytown.

As an architect at Glave & Holmes Architecture and president of the Partnership for Smarter Growth, Moore has high hopes for the mall and the surrounding commercial area. Despite the relative walkability of Westham – his children can walk to the local elementary school – he thinks Henrico could be more livable. He is looking for somewhere pleasant to hang out, walk around and spend time with family and friends, with connections that don’t depend solely on the automobile. There are places where he can do that but they’re mostly in Richmond, like Carytown. Henrico desperately needs something comparable, he says.

“It has lots of potential,” Moore says. “But not as a mall.”

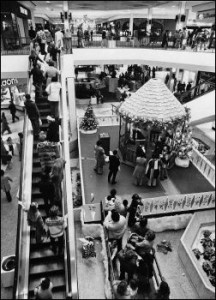

In 1977, not long after it opened, Regency Square was a destination – a center of fashion, especially at Christmas, when visitors would come from miles around to see Santa.

Opened in 1975, Regency Square was designed as a classic enclosed suburban mall surrounded by vast parking lots. The business model was predicated on people driving to the shopping center in their cars, parking and spending time inside protected from the elements. Enclosed malls helped define post-World War II American suburbia and the auto-centric lifestyle. They were the closest thing to public gathering places that many suburban communities offered.

Over time, tastes evolved. As Americans became more aware of environmental issues, many became disenchanted with the idea of driving to every destination in their automobiles. Concerned about the lack of exercise in their sedentary lifestyles, they placed a premium on walking and biking. As a practical matter, the suburbs were impossible to redesign as walkable communities. Zoning codes separated land uses – houses here, offices there, retail over there – by distances too vast to walk. Most streets and roads were inhospitable to pedestrians in any case. In the early 2000s, developers emulated walkable neighborhoods by building open-air malls such Short Pump and Stony Point. They are oases of walkability, but they didn’t create organic communities. They are disconnected from surrounding neighborhoods; people still have to drive to get there. The only things to do are shop and eat.

Since the housing collapse of 2007-2008, metropolitan development has undergone an even more profound shift. Millennials are less devoted than their parents were to the auto-centric lifestyle. Educated young people prefer what urbanist Christopher Leinberger calls “walkable urbanism” in neighborhoods with a fine-grained mix of jobs, housing, shopping and amenities. For the first time since World War II, many Americans are moving back into urban neighborhoods with walkable streets. Where the young people go, employers have begun to follow. Gentrification and redevelopment in core walkable neighborhoods can’t keep pace with demand, however, so across the country developers are revamping older suburban districts or building walkability into new developments.

Meeting the surging demand for walkable urbanism is one of the great challenges facing Henrico today. Most of the county’s development took the form of post-World War II suburbia – low-density subdivisions and shopping centers knitted together by connector roads and arterials. By design, no one walked anywhere; everyone drove. But it’s not clear that the development formula that worked for Henrico in the 20th century will continue working in the 21st century.

Henrico County’s Comprehensive Plan recognizes this reality by designating Regency Square and the rest of the commercial district around the intersection of Parham and Quioccasin roads as one of several “special focus areas.” Redevelopment, says the plan, “should be done in a manner to create a cohesive, walkable neighborhood with pedestrian connections to the surrounding residential areas.”

Tuckahoe Supervisor Patricia O’Bannon says she would like to see the Regency Square area evolve in concert with the needs and preferences of western Henrico households. That would mean redeveloping Regency Square and adjacent commercial areas as a place where Henrico residents can follow the life cycle – single adults, young married couples, families with kids, empty nesters, retirees – within the same community. O’Bannon says she hears repeatedly from constituents who want to stay in Henrico, with its good schools and low crime, near family and friends. To do that, they need a variety of housing types, not just garden-style apartments and single-family homes, and they would like to be able to walk to destinations such as restaurants, schools and shopping. “They don’t want to drive everywhere,” she says.

It’s a vision that may not be out of reach. Vacant land available for traditional subdivision development is disappearing in western Henrico, says Joe Emerson, the county’s director of planning. The economics of development will support higher land prices and higher densities. “As the county urbanizes,” he says, “you’re going to see taller structures” allowing for greater variety of housing types and neighborhood configurations. Landowners will convert parking lots into buildings, and they will build parking decks to accommodate the cars. The county will see more mixed-use buildings and walkable streets. Regency Square is one of the places where that might happen. The area’s potential, he says, is bounded only “by the imagination – and the marketplace.”

Large commercial properties like Regency Square don’t change hands very often, especially not in circumstances where a new developer has the opportunity to start with a blank canvas. Though only 25.6 acres, the property up for sale is strategically important.

First, it is the key parcel in the four-parcel mall property. The other three parcels are owned by Sears, J.C. Penney and Bridgestone Tire. The property for sale includes the mall proper, two Macy’s stores and an expanse of parking lots, and a developer would be in a position to drive redevelopment of the entire complex in cooperation with the other property owners.

Second, Regency Square is the foundation of a larger business district at the intersection of Parham Road and Quioccasin. The larger district encompasses nearly 150 acres, 50 parcels and property assessed at $136 million. If revitalized, this beating commercial heart of southwestern Henrico could become a community asset that would enhance the quality of life for nearby residential neighborhoods.

Few believe that Regency Square has much chance of reinventing itself as a regional mall on the scale of, say, Short Pump Town Center. While it is served by an important arterial, Parham Road, which serves 40,000 cars per day, any mall would be hard-pressed to compete with Short Pump, which is served by Interstates 64 and 295, and surrounded by tracts of expensive subdivisions with high-income households. Regency Park and Beverly Hills, the neighborhoods immediately adjacent to Regency Square, tend to consist of smaller homes built in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Many would be considered starter homes for middle-class families. They are solid middle-class neighborhoods, but hardly affluent compared to Short Pump.

The average age of the population skews a little younger than the countywide average, says Emerson, whose department conducted an extensive survey of the area for an October report that was delivered to the Board of Supervisors. He describes Regency Park and Beverly Hills as “neighborhoods in transition,” with older folks moving out and younger, more ethnically diverse households moving in. “Property values are in the affordable range. They’re very solid homes – a lot of brick, good construction.” Neighborhood schools, especially Douglas Southall Freeman High School, are a big draw.

The numbers suggest that residential neighborhood values are stable. A survey conducted by county employees driving through the neighborhoods found that 90 percent of the structures and 60 to 70 percent of the landscaping are in “good” condition, Emerson says. “Overall, the neighborhoods are impressive for their age. … This area is doing remarkably well, we think, and we want to keep it that way.”

Likewise, commercial properties in the area seem to be faring well – other than the mall, of course. Wal-Mart and Kroger are going gangbusters, Emerson says, and there are few vacancies in the area. That’s an indicator that there is plenty of buying power to support businesses catering to the roughly 60,000 or so inhabitants of the regional submarket that surrounds Regency.

While the demographics are strong, anyone wanting to redevelop Regency Square Mall would face several challenges. First, they would have to get buy-in from the other property owners, in particular Sears and J.C. Penney. Both retailers are experiencing difficulties nationally, however. Indeed, it may be fair to describe Sears as a long-term real estate play in the guise of a department store. Brian Glass, senior vice president for commercial real estate firm Colliers International in Richmond, says either retailer could be persuaded to shut down its store if there is a good redevelopment opportunity. “If someone came in with a master plan, I wouldn’t doubt that Sears and Penney’s would cash in their chips,” he says. Still, that’s an uncertainty that any would-be developer would have to consider.

Another obstacle to redevelopment of the mall is topography. “Regency is a two-story mall with a two-story parking deck. This is a tough one to redevelop. It’s not like Cloverleaf, where you could knock down a one-level building on a level, paved area,” Glass says, referring to the former Chesterfield County mall that was transformed into a grocery-anchored mixed-use project. “This is on a hill. It’s more complex.”

On the other hand, Henrico can offer inducements to any developer. The mall sits in an enterprise zone, which might qualify for targeted state grants and tax breaks. Also, Henrico offers a generous real estate tax abatement program. For properties more than 26 years old, the county freezes the real estate tax assessments for seven years when property owners make major improvements. This means the property owner doesn’t pay taxes on the increased value of the property. Says Emerson: “When you talk about the cost of upgrading the mall, that’s not an insignificant amount of money.”

Ellen Dunham-Jones, an architecture professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and co-author of the book, “Retrofitting Suburbia,” has compiled a database of more than 900 case studies of suburban redevelopment projects across the country. She has observed that mall retrofits fall into three broad categories: regreening, reinhabitation and redevelopment. She is not familiar enough with Regency Square to say which strategy would work best, but she does offer some guidelines for judging the market potential.

A surprising number of malls were built over creeks and streams, running conduits underneath to channel stormwater. As surrounding areas developed, stormwater would back up and cause flooding, with the result that redevelopment consists of restoring wetlands and free-flowing creeks. Stormwater flooding has not emerged as an issue in the Regency Square area, so regreening does not appear to be a likely path.

The reinhabitation strategy preserves the mall structure but changes the mix of occupants. Dunham-Jones points to other malls that have been anchored by medical facilities or educational institutions. These activity centers draw people who patronize the restaurants and retailers. A variation on the reinhabitation theme, discussed by local observers of the Richmond real estate market, would be converting the enclosed mall to an open, walkable shopping center, as developers have done with The Shops at Willow Lawn. Reinhabitation appears to be a plausible option for Regency Square, although there is some competition just down the road, at Stony Point Fashion Park.

But the idea that gets people really excited is what Dunham-Jones refers to as “redevelopment” – tearing down the mall and smaller outbuildings and reconceiving the entire property as a mixed-use project at much higher density. Under Henrico’s growth guidelines, redevelopment facing neighborhoods of single-family houses would restrict building heights to 35 feet, but would allow building heights to increase in stair-step fashion toward the center.

Emerson, the planning director, says the guidelines would support office or residential towers of 10 to 12 stories in height, which is taller than almost anything standing in Henrico today. (The tallest structure outside the Richmond International Airport control tower is a 13-story apartment building near Willow Lawn.) County design guidelines also would regulate landscaping, entrance features, street setbacks and other features. The county Comprehensive Plan calls for completing a “detailed study” to determine the best mix of land uses, transportation and the best way to encourage revitalization and reinvestment.

The time to conduct such a study is now, suggests Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth. Although his group advocates for smart growth in the Washington metropolitan area, Schwartz lives in Richmond and serves on the board of the Richmond-focused Partnership for Smarter Growth. “It’s better to do the plan early – before a developer gets too far down a certain path,” he says. Any plan, he says, should pay special attention to “place making” – the details of creating a place where people want to be, such as town squares or other public spaces, parks and streetscapes.

What the Regency Square commercial corridor could become if the area were redeveloped with an inter-connected street grid like Carytown. The new streets, in yellow, would transform the area into a walkable shopping, office and residential district.

Moore, the president of the Partnership for Smarter Growth, is an architect by training. He’s a fan of new urbanism, a development strategy that echoes pre-WWII patterns, emphasizing the value of building on a human scale, paying particular attention to the public sphere and not elevating the automobile over walking and other forms of transportation. Ideally, he says, the new Regency Square would contain a publicly owned “village center” with a plaza or park where people could gather. It would be served by a grid-like matrix of streets connecting to adjacent neighborhoods and shopping centers, and it would allow for “complete streets” that accommodate not just cars but pedestrians, bicycles and mass transit.

A good long-term plan, Moore says, would allow neighboring shopping centers to evolve into a mixed-use pattern. A plan might even extend to Parham and Quioccasin roads, congested, crowded street-road hybrids that fulfill neither the local-connectivity function of streets nor the high-capacity, high-speed function of roads very well. Travel speeds are already so low on Parham that the road conceivably could go on a “road diet” that narrowed the lanes, reduced posted speeds and freed up space for pedestrians, on-street parking or bicycles without sustaining a loss in drive times.

Integrating the town center into the surrounding urban fabric would make it a more desirable location for people to come visit, Moore says, and it would make it easier for people to get there without hopping in their cars and taking up parking spaces. Mixed-use development would allow people to “live, work and play” in the same part of town, without needing to get into their cars. Creation of a town center would transform life for children and seniors as well.

“Wouldn’t it be great if kids could walk or ride their bikes to Freeman?” Moore says. “Or, if you’re a senior, to get to a grocery store by walking?” Indeed, a connectivity plan might even include mass transit, which would integrate the town center with a broader geographic area. The goal, he says, would be for neighborhoods from miles around to not just consider the Regency Square area as their center of commerce, but “the center of their village – a place to hang out with friends and neighbors.”

O’Bannon, the Tuckahoe supervisor, supports the evolution of Regency Square into a walkable, mixed-use area, and she’s willing to see the county invest more in sidewalks, but she’s skeptical of bicycles and mass transit. She says her constituents want to walk, not ride bikes or take the bus. She says there is a bright future for shared ridership, but it probably looks more like Uber or Lyft car-sharing than the public buses.

Whether the Regency Square area moves toward a full-fledged town center concept like the one Moore proposes or a modified version like the one O’Bannon supports, it will require significant public investment. Someone will have to pay to complete the grid street system and to transform car-focused thoroughfares into pedestrian-friendly streets. In many redevelopment projects, developers and landowners are willing to foot the bill with the expectation that their properties will become far more valuable. But not always.

Moore argues that Henrico could justify making some public investment on the grounds that squeezing more stores, offices and apartment buildings into the same space that exists now would generate higher property tax revenues. Dunham-Jones cites research that “regionally significant” walkable urban places in the Washington, D.C., area command higher rental premiums for office space.

At the current tax rate of 87 cents per $100 in assessed value, commercial properties in the Parham-Quioccasin area generate about $1.2 million in property taxes. To use some rough numbers: Converting half the parking space to buildings, boosting the average building height to three stories and raising per-square-foot rents could quadruple assessed values and real estate tax revenues, easily yielding the county an extra $2 million to $3 million yearly, some of which could be used to float county bonds for public improvements. Setting aside $1 million of the new annual tax revenue, for example, could be used to pay off bonds of roughly $12 million to $13 million – not including the gains to property values in surrounding neighborhoods that would accrue from having a desirable amenity nearby – with plenty left over.

Would the market support such a dramatic transformation of the Regency Square area? Urban living has been validated in Richmond, where retrofits of old commercial and industrial buildings continue apace. There are positive signs as well from projects such as Libbie Mill and West Broad Village in Henrico. West Broad Village, a successful but isolated mixed-use project jammed with three-story residences along walkable streets, may be the best indicator that there is a demand in the suburban marketplace for mixed-use development. If redeveloped correctly, connecting with surrounding neighborhoods and business areas, Regency Square could easily become the premier “urban” neighborhood in suburban Henrico.