Several years ago Brookings Institution urbanist William H. Frey proclaimed the 2010s as “the decade of the city.” A constellation of forces in the knowledge economy, which puts a premium on dense, mixed-use urban environments with access to mass transit, was pulling Millennials and corporations back into central cities. It was a logic that I subscribed to, although I did raise the warning that there were limits to how much growth cities could absorb, given zoning, regulatory and other growth restrictions that limit the pace of urban redevelopment.

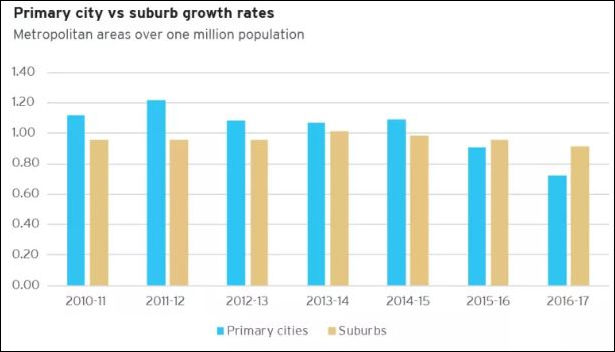

Now, citing new U.S. Census data, Frey has found that big city growth rates have leveled off and suburban growth rates are reviving. He writes:

The new numbers for big cities—those with a population of over a quarter million—are telling. Among these 84 cities, 55 of them either grew at lower rates than the previous year or sustained population losses. This growth fall-off further exacerbates a pattern that was suggested last year. The average population growth of this group from 2016 to 2017 was 0.83 percent—down from well over 1 percent for earlier years of the decade and lower than the average annual growth rate among these cities for the 2000 to 2010 decade.

The Washington metro was an exception to the trend. Population of the “primary city” (which I presume refers to Washington, D.C., although it may include Arlington and Alexandria) grew 1.5% between 2016 and 2017, exceeding the 1.0% rate for the suburbs.

In the Richmond metro, the population of the primary city (presumably the City of Richmond) gained 0.8% over the same period, slightly slower than 1.0% rate for the suburbs.

In the “Virginia Beach” metro, the population of the primary city (I’ve got no idea which localities Frey might be counting) actually declined 0.3% while the “suburbs” grew 0.8%.

Frey does not try to explain why the urban growth spurt has slowed. I stick with my original theory that there is an untapped demand for urbanism but urban areas have limited capacity to absorb new growth. Urban-core localities have little vacant land to develop, and strong NIMBY forces inhibit redevelopment at higher densities. Preservationists want to protect historic buildings. Homeowners fear traffic impact. Property owners want to protect view sheds from tall buildings.

NIMBY forces are at work in outlying jurisdictions, too, but there is a backlog of zoned projects from the 2000s real estate boom, and there are vast areas dedicated to industrial/commercial uses that can be rezoned with only modest impact on adjacent neighborhoods.

Bacon’s bottom line: Core urban jurisdictions can’t grow their populations any faster than they can redevelop — and they can’t redevelop very fast. As urban property values rise, many people have no choice but to locate in suburban localities where land values are cheaper. Perhaps the best opportunities for real estate developers in 2018 are in retrofitting the obsolete economic mono-cultures of shopping centers and office parks into vibrant, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods that emulate the urbanity of city centers.