Ninety-two percent of Virginia’s public schools are meeting the state Board of Education’s expectations for achievement on the Standards of Learning exams, thus winning them “accredited” status for the 2019-20 school year, the Virginia Department of Education reported today.

“This is the second year that schools have been evaluated under the 2017 Board of Education-approved accreditation standards, and this new system for measuring the progress and needs of schools is doing exactly what it was designed to do,” said Superintendent of Public Instruction James Lane. “These latest ratings will help VDOE target its efforts toward increasing student literacy and furthering progress toward eliminating achievement gaps in the schools that are most in need of the department’s support and expertise.”

The new system creates a new category, “accredited with conditions,” that allows previously poorly performing schools to avoid facing sanctions. Ironically, while this system is “doing exactly what it was designed to do,” according to Lane, overall SOL scores statewide declined in the 2018-19 school year, and the “achievement gap” between Asians and whites on the one hand and Hispanics and blacks on the other showed no sign of improvement.

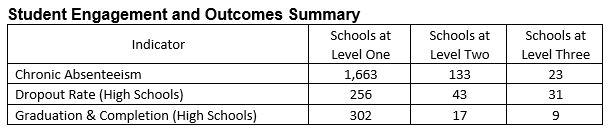

As one sign of supposed progress, Lane cited the fact that the number of schools meeting the state board’s goal for reducing chronic absenteeism by 4% — from 1,600 schools to 1,663. “Last year’s ratings compelled school divisions to focus on the need to reduce chronic absenteeism,”he said, “and their success in improving student attendance is reflected in the ratings for 2019-2020.”

Question: Could there be a direct link between the success in improving attendance (reducing chronic absenteeism) and eroding test scores?

I understand the logic behind reducing absenteeism. If a student is skipping school, he or she is not attending classes. If students are skipping classes, they probably aren’t doing their homework either. Indeed, the odds are good that they’re not learning anything — nothing related to their academic subjects at least. Therefore, if school officials can round up truants and stick them back in the class, maybe they can learn more. And if truants learn more, maybe they can pass their SOLs and eventually graduate from high school.

But there’s another possibility. What if the kids who play hooky are the kids learning the least from class — possibly because they have been socially promoted and have reached the point where they don’t understand the material, they’re really bored, and they resent being there? What if these very same kids are disproportionately likely to be disruptive in class? Is it possible that the policy of forcing these kids into school contributes to a poor learning environment for the kids who do want to be there?

I doubt that anyone has answers to these questions, because I have seen no evidence that anyone at VDOE is asking the questions in the first place. But here’s what VDOE could do: It could separate, statistically speaking, the chronically absentee kids from the other kids, and it could compare their SOL pass rates with those of kids who regularly attend. That way we could whether rounding them up and shipping them to school actually has a beneficial effect on them.

VDOE also could see if there is a significant overlap between chronically absentee kids and those who create discipline problems in school. We could evaluate whether the effort expended in rounding them up and shipping them to school has a detrimental effect on other students.

It would be useful to know the answers to both sets of questions.

In an ideal world, we would like to see every child graduate from high school. But in the real world we live in, we need to ask whether that is, in fact, an appropriate goal. Might not some kids be better off finding an entry-level job and learning how to conform to a workplace culture than slouching around school and learning nothing? Might not the expectation that every kid must graduate from high school reflect a white, elitist cultural bias at odds with the values of non-white groups, Hispanics in particular, who believe that teenagers should work and contribute income to the family?

I don’t have the answers. But I think it’s important to challenge the conventional wisdom, especially when the ruling K-12 educational dogma is visibly failing.