The variability in health insurance by Virginia city and county accounts for 30% of the difference in health outcomes rank. What explains the other 70%?

A dominant strain of political rhetoric tells us that having health care insurance is absolutely vital to maintaining peoples’ health and longevity. Without health insurance, people will die! The logic makes sense if one assumes that the United States (and Virginia) have a binary health care system in which people either (a) have health insurance (including Medicaid and Medicare), giving them full access to the health care system, or (b) lack insurance and receive no medical treatment. But in the real world, there’s a big fuzzy zone. Some insurance, frankly, stinks — limited choices, high deductibles and the like. And some uninsured people enjoy at least limited access to medical care at clinics, emergency rooms and hospital care.

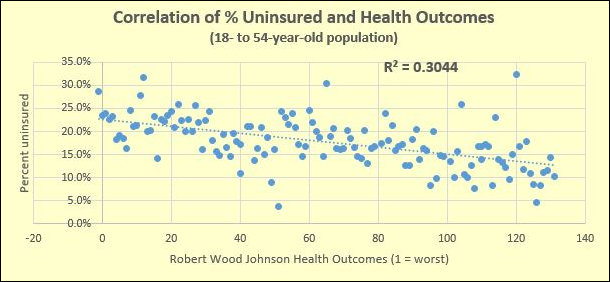

On a lark — I honestly had no idea what results I’d get — I created a scatter graph comparing two data sets for 132 Virginia counties and cities. One comes from the StatChat blog: Health Care Coverage Across Localities in Virginia in 2015, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey. The other comes from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation 2017 County Health Rankings, which ranks city and county health outcomes on a basket of health quality and longevity metrics.

The chart above shows the results. As one would expect, there is a significant correlation — localities with lower percentages of uninsured working-age populations tend to have better health outcomes, and vice versa, higher percentages of uninsured populations translate into worse health outcomes.

But the R² coefficient is only .3044. That’s statistics-speak for saying that the variation in the percentage of the insured population accounts for only 30% of the variation in health-outcome rankings. (Note: that’s health-outcome rankings, not actual health outcomes. I readily concede that this is a quick-and-dirty analysis.) Thirty percent is significant, but it leaves a lot unexplained. Seventy percent of the variance is due to other factors.

The debate about health care in the United States over the past half century has focused mainly on expanding access to health insurance as a way of expanding access to medical treatment. But insurance accounts for maybe 30% of the problem. What about the other 70%? The Robert Woods Johnson (RWJ) attributes the following weights to different health factors:

- 30% — health behaviors (tobacco use, diet & exercise, alcohol & drug use, sexual activity);

- 20% — clinical care (access to care, quality of care);

- 40% — social & economic factors (education, employment, income, family & social support, community safety);

- 10% – physical environment (air & water quality, housing & transit).

Here in Virginia, Democrats are obsessed with Medicaid expansion, as if the percentage of population with insurance is the be-all-and-end-all of health policy. Unfortunately, Republicans have offered few reasons to oppose Medicaid expansion other than to emphasize the stress it would impose upon state finances.

Instead perpetuating this sterile debate out of partisan loyalty or antipathy to former President Obama’s signature legislative achievement, we should ask if we can make bigger gains in health outcomes at less expense than by expanding Medicaid. The RJW report gives heavier weight to personal behavior as reflected in smoking, substance abuse, sexual activity, nutrition and exercise. Perhaps the politicians should, too.