“To listen well is as powerful a means of communication and influence as to talk well.”

— John Marshall

by James Wyatt Whitehead V

John Marshall, fourth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, wore the same judicial robe for 34 years. Preservation Virginia, which maintains the John Marshall House on Marshall Street in Richmond, displays the garment, one of the greatest relics of the U.S. Supreme Court, since 1911, when Marshall’s great granddaughter donated it.

Wear, time, light, temperature, and humidity took a toll on the artifact, but a 12-year preservation campaign to “Save the Robe” resulted in success. On April 15th via a webinar, Marshall’s robe was revealed to the public once again.

John Marshall was born on September 24th, 1755 in a small Fauquier County settlement known as Germantown. Like most Virginians, he was born in a simple log cabin. By his early youth the Marshalls had upgraded to a two-room log cabin in Markham. Marshall, like George Washington, had little in the way of a formal education. But John’s father, Thomas Marshall, had an important connection with Washington. They had surveyed Lord Fairfax’s vast land holdings together and had served as comrades at Fort Necessity during the French and Indian War. In the era of the American Revolution, Colonel Thomas Marshall and son John had endured the hardships of Valley Forge and waged successful rear-guard actions to save Washington’s beleaguered forces from destruction at the Battle of Brandywine.

In 1780, while on furlough, John Marshall attended The College of William and Mary, where he studied law under the watchful eye of the father of American law, George Wythe. A successful law practice was launched and Marshall entered state politics as a member of the House of Delegates. President Washington, Marshall’s idol since childhood, offered him the positions of U.S. Attorney for Virginia and the high office of U.S. Attorney General. The future chief justice turned down both of Washington’s offers to remain focused on his law practice. During the administration of John Adams, John Marshall was one of the diplomats tied to the famous X,Y,and Z Affair that led to the quasi-war with revolutionary France. Marshall continued to serve John Adams as a loyal Federalist Congressman and Secretary of State. In the role of the latter, Marshall peacefully concluded the conflict with France and the never-ending struggle with the Barbary Pirates.

On February 4th, 1801, Marshall was sworn in as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He made his way to the bench via the controversial Midnight Judges Act, a last-minute Federalist court-packing bill from the Adams administration. One year later the foundation of America’s Constitution was strengthened in the case of Marbury v. Madison For the first time in the 16-year infancy of the nation, a federal law had been struck down by the Supreme Court. The principle of judicial review elevated the court as a coequal to the executive and legislative branches of government. In the ruling Marshall succinctly stated, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”

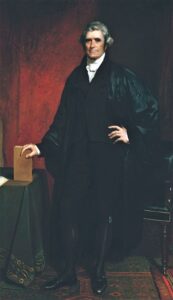

For 34 years, Marshall wore the preserved judicial robe while administering his duties in the Old Supreme Court Chamber. The chamber was in the basement of the U.S. Capitol and lacked the grand setting of the modern court At a height of six feet and one inch and a lean weight Marshall’s robe was extra-large for his size. In the portrait, by Chester Harding, we see John Marshall standing erect with the robe draped over his arms It was the only way to carry the supplemental black silk cloth. Robes had adorned judges since 15th century English courts. The first Supreme Court judges, such as John Jay, wore a scarlet robe. Thomas Jefferson suggested something less conspicuous and insisted on discarding powdered wigs. John Adams admired the trappings of British customs and wanted to keep the traditions alive. John Marshall settled for a compromise. The wigs had to go but the robes would stay in form of a black robe to symbolize neutrality. It might have been the only time Jefferson and Marshall agreed with one another.

During the robe reveal webinar, Roger Gregory, chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, had this to say about John Marshall’s robe:

Marshall brought more than a robe to the Supreme Court, he added power and prestige. The color, black, is an amalgamation of colors and represents the wide range of the American people. The color represents neutrality of justice and the promise to adhere to justice. The black robe also suspends bias to promote the impartiality of the court.

Saving the robe would require the expertise of Howard Sutcliffe, the director of Birmingham Alabama’s River Region Costume and Textile Conservation. Sutcliffe’s initial examination revealed the extent of 220 years of damage. The robe was covered in patches from five previous restorations. The seams had frayed and the hem line was pulling away from the fabric after 34 years of dragging across the floor of the Supreme Court. The delicate silk fabric had split all across the back of the robe The dye used to create the deep black color had started a damaging process of acid hydrolysis. The collar was visibly stained by John Marshall’s sweat and the sleeves were frayed from the years of Marshall’s desk work. Sutcliffe remarked that restoration would be a challenge. But challenges were right up his sleeve for a man who had restored relics from Andrew Jackson’s top hat to the original Kermit the Frog puppet.

The first order business for the conservator was to remove the numerous small square patches and other previous restorative work. Next came the relining of the robe from the interior coupled with a painstakingly slow process of hand restitching frayed areas. Nearly 300-man hours were dedicated to this delicate restorative process. The Save the Robe Campaign raised $218,000. Half of the money went to the preservation work and the other half will go towards new interpretive signs at the John Marshall House. The virtual reveal displayed a renewed John Marshall judicial robe that will not need a touch up for generations.

I asked Judge Gregory for his thoughts on this statement:

“t is often said that John Marshall is the most important American who was never elected President.

Gregory agreed. “Washington and Marshall are the only Americans who fought for freedom in the Revolution and then shaped the working of government to preserve that freedom.”

The curator of John Marshall House called the restored robe a “witness artifact.” After the historic case of Marbury v. Madison, Marshall would continue a brilliant career on the bench of the Supreme Court. Cases such as McCullough v. Maryland, Gibbons v. Ogden, and Dartmouth College v. Woodward may seem like stale material from an old high school government class, but they shape citizens and our interaction with government every day. Marshall’s ascendency to the high court was an effective check against Jefferson’s Virginia Dynasty and the fickle nature of the early U.S. Congress. He presided over the trials of the century in the drama of Aaron Burr’s conspiracy and the impeachment of Salmon Chase. One opponent proved to be more than Marshall could handle: Andrew Jackson. When the Marshall court ruled in Worcester v. Georgia against Jackson’s Indian policies, Old Hickory’s rebuttal proved to be a threat to the power of the Supreme Court: “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!”

Late in life John Marshall completed a long-held ambition. A five-volume, 1,000-page biography, The Life of George Washington. Panned at the time as Federalist political propaganda the work remains an authoritative source on the most indispensable American. On July 6th, 1835 John Marshall died in Philadelphia, Pa. Marshall miscalculated by two days from joining the Fourth of July club of Jefferson, Adams, and Monroe. At age 79, he was still the Chief Justice and the last Founding Father centurion of the Revolution. He is buried not in Hollywood, but Shockhoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond.

In his old age, John Adams proclaimed, “My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.”

John Marshall House and the conserved robe are open to the public. Regular hours are Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Private tours can be scheduled as well.

by James Wyatt Whitehead V is a retired Loudoun County school teacher.