The Wall Street Journal cited a revealing statistical measure of the COVID-19 virus that reflects upon the ability of different health systems to cope with the epidemic: the percentage of confirmed cases that result in fatalities. That number varies widely across countries and states.

The focus of the article was Singapore and Honk Kong, two densely packed cities that have kept the deaths-to-infections deaths ratio extremely low: 0.4% in Hong Kong and less than 0.1% in Singapore. Not only have those cities done a better job than the U.S. of containing the spread of COVID-19, the virus has proved to be less fatal when people get it.

By contrast, the case-fatality rate in the U.S. overall is 5.9%. That’s high, but not as high as the United Kingdom and Italy, where the figure stands at 14.%. In the U.S., New York City the rate is 8%, according to the Journal.

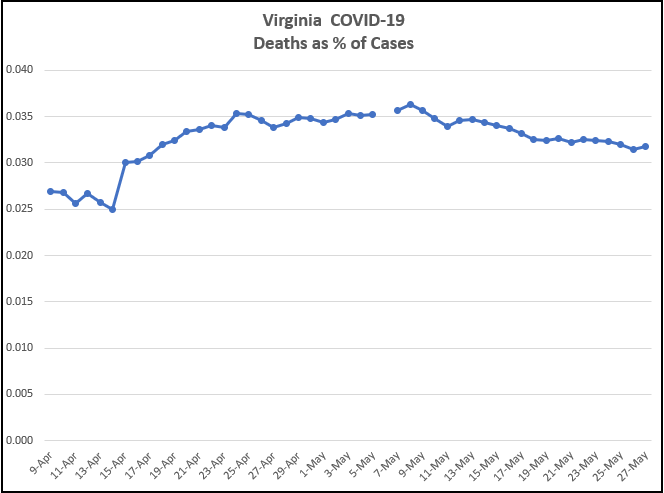

What about Virginia? Our case fatality rate peaked around 3.6% and has since declined to 3.2%, based on data published on public dashboards this morning. As can be seen above, the rate increased steadily from early April to early May, crested May 9 and 10, and has declined fairly steadily since.

What accounts for the differing case-fatality rates?

“When you overwhelm health systems a lot more people die,” the Journal quotes David Owens, founder of Hong Kong medical practice OT&P Healthcare as saying. “Hong Kong and Singapore “didn’t let the epidemic get out of control.”

Also, writes the Journal: “Keeping infections from spreading to communities most at risk allowed both cities to manage their medical resources. Doctors and researchers, free from being inundated by a crisis, have been able to focus on finding treatments.”

And that, ladies and gentlemen, brings us to a crucial but neglected point in the COVID-19 debate. As docs and researchers gain more experience with the virus and more scientific understanding of how it attacks the body, they are getting better at treating the disease.

That raises interesting questions here in Virginia. Have Virginia hospitals done a better job on average compared to their peers in other states of treating the virus? The fact that our case fatality rate is significantly lower suggests that they might have. On the other hand, Virginia hospitals, despite shortages of personal protective equipment, were never overwhelmed to the same degree they were in New York City. Also case fatality rates likely vary by the types of patients being treated. Elderly patients with more coexisting conditions are more likely to succumb. If Virginia hospitals were treating healthier patients on average, that might explain their better performance. Not having access to that data, I’d have to refrain from drawing any conclusions.

A stronger case can be made that Virginia physicians and hospitals, by virtue of learning more about the virus, are getting better at treating patients — just as their peers are across the country. Are Virginia health practitioners figuring out which types of treatments work best, or which combination of treatments work best in specific cases? The declining case-fatality rates suggests that perhaps they are. There may be other explanations for the declining rate, but it is a reasonable hypothesis.

If that hypothesis holds up — if improving treatments are driving down the fatality rate — we can all take comfort.