by James C. Sherlock

by James C. Sherlock

Virginia school districts desperately need to find ways to improve public education for poor minority children.

The lowest performing schools are concentrated in urban areas, but, as I have shown here, are present in even America’s richest county, Loudoun.

Charter management organizations (CMOs), non-profits who operate two or more charter schools, focus on educating those very students. The best, like New York’s Success Academy, have produced spectacular results with the very kids whom many Virginia schools are failing. But they will not locate in Virginia right now due to our laws. They would not be able to operate here in the manner that has made them successful.

This article will show what is necessary for Virginia to position itself to compete for their services for the kids we most often fail to educate.

We really must do it.

I have in earlier posts pointed out that Virginia is rated by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (NAPCS) as sixth worst state of 44 in the friendliness of our charter laws to charter school establishment and operation. NAPCS publishes a model law that can guide the necessary revisions.

In 2016 NACPS, ExcelinEd and Ampersand Education surveyed the top performing CMOs to determine what might encourage them to expand into a new territory. The answers are of direct importance to Virginians, including the Youngkin administration, seeking to improve failing schools.

Virginia currently has seven charter schools, none operated by a CMO. None of them target poor minorities to the degree that the best CMOs do. And none is nearly as successful in educating poor minority children as the best CMOs.

But what is important to the most successful organizations also gives leads on what is important to improving the success of our existing charter schools.

Some may find the survey answers intimidating. But if we want finally to educate poor minority kids trapped in our worst schools, we will give them what they ask. Only hubris will prevent us from doing so.

The survey addressed the following:

- “The process and timing for CMO growth

- The autonomies and freedoms CMOs view as “must have” versus “nice to have” to operate effectively in a new geography

- The level of funding and facilities support CMOs need to operate effectively

- The human capital policies and supports CMOs need to open new schools

- The demographic characteristics of a new geography that CMOs seek

- The preferences of CMOs regarding charter authorization and governance.

Process and timing for growth.

“The largest CMOs surveyed (those with more than 5,000 students and operating 10 or more schools) were more comfortable with moderate or rapid growth, less flexible on their requirements for growth, and more willing to expand. These CMOs know have a proven track record and are excited about growth, but only under the best of circumstances.”

Nearly 90 percent of these CMOs are willing to open new schools at a slow (grade by grade) or accelerated (multiple grades per year) pace; only 41 percent are willing to engage in the turnaround of an existing school.

Of those networks willing to attempt a turnaround of an existing school, none is willing to attempt a turnaround of an existing public school without the ability to replace the existing staff with a new staff. CMOs believe that they have the best chance of success with families if they “start fresh.”

This inflexibility is not the result of stubbornness but of wisdom gained through experience.”

Autonomies and freedoms for charter schools that influence CMO decisions to expand.

Key charter autonomies around budget, curriculum, personnel, and school culture are seen as nonnegotiable by all CMOs surveyed. CMOs reported that they need to have control over these issues if they are moving into a new geography.

Over half of CMOs surveyed also require the freedom to determine staffing models, compensation and benefits, formative assessments, structure of the school day and year, and board size and composition.

CMOs believe they know what it takes to run a successful network of schools—including these key operational features—and they will not open schools unless they are guaranteed this autonomy. (Note: They are not interested in temporary waivers — they represent long-term risk.)

Funding and facilities support sought by CMOs.

On average, the CMOs surveyed reported needing at least $10,200 in per-pupil (2016) public funding to operate effectively.

However, this single number masks a great deal of nuance in CMO funding needs. Said one CMO leader, “It’s not as simple as per-pupil or facility assistance. … We want to make sure our overall financial equation works.” Different operating models cost different amounts, and CMOs must also take scale into account in a given region. For example, a CMO with more schools in a region may be able to subsist on lower per-pupil funding because the fixed regional office costs are spread over more schools or students. As one CMO leader pointed out, “Market specifics such as special-needs student demographics, transportation costs, and required student-to-teacher ratios can have a major impact.”

CMOs also stressed the importance of startup funds in their expansion decisions—all respondents rated these funds as “must have” or “nice to have.” While most CMO models are sustainable on public funding alone once at full enrollment, interview participants cited that their networks run deficits of up to $1.5 million annually as campuses expand to

full enrollment. Similarly, most CMOs will staff a regional support office before opening their first schools; the cost of this regional office is also generally supported through one-time grant funding until a CMO’s enrollment is sufficient to pay for these shared support services on regional public funding alone. While these startup funds are often secured from private philanthropists, federal and state charter startup grants can also fill this role and make states more compelling options for CMO expansion.Facilities are a crucial component of a CMO’s funding equation. As one interviewee pointed out, “There almost isn’t enough philanthropy to think about substantial scale in a state if there isn’t a way to access existing school facilities.” Another CMO leader explained ideal facilities this way: “We need something close to kids, in reasonable condition, at a reasonable price.”

Human capital policies and supports needed to enable CMO success

Three-quarters of CMOs surveyed saw a supply of high-quality teachers and leaders as essential to their expansion into a new city or region. Interviews revealed that availability of high-quality teachers and leaders is perhaps the key constraint for CMOs looking to expand into new regions.

However, specific definitions of “high quality” vary among CMO respondents. What do CMOs see as reliable pipelines for high-quality teachers and leaders? Teach for America (TFA) alumni are at the top of the list. One CMO leader pointed out that the presence of TFA in a market—as well as the number of TFA alumni—is a good proxy for the teacher pipeline in a region. That said, some operators specifically noted in interviews that their models require teacher pipelines that differ from TFA because of a focus on nontraditional pedagogical approaches. New teachers trained in-house are the third key source of human capital for CMOs. CMOs also rank their own teachers as a preferred source of talent in a new region, which is enabled by policies that allow charter teachers to transfer licensure to a new state.

Some CMO leaders prioritize leader talent above teacher talent. One CMO leader reported, “We won’t consider going into a new region until at least two strong leaders (a regional executive director and a founding school leader) are identified.” Finally, the survey data reflect that CMOs do not want their pool of potential school leaders reduced by rigid certification requirements.

Characteristics of potential expansion regions that influence CMO growth decisions.

“Most important, CMOs seek (1) the presence of local philanthropic funds needed to support school startup costs and (2) clear indications that there is need for high-quality schools as demonstrated by inadequate educational options within a given community.”

Enrollment share matters to some CMOs. One CMO leader reported, “We don’t necessarily need to be the largest school system in a region, but we want to be able to educate enough students (10-20 percent) to make a significant impact on a city or region.” Another leader said that, in general, “[w]e probably wouldn’t open in a new region with [a plan to have] fewer than six schools or less than 5 percent of the school-aged population.” Other CMOs mentioned that their network typically opens a relatively small number of schools in each city or region, so the depth and breadth of student need and parent demand is less important.

The potential to join a cadre of other high-performing CMOs entering a new region can also be very attractive to a CMO considering expansion.

One CMO leader pointed out that the stability of the local political environment matters as much as the current level of support: “It’s disconcerting how fast the [political] pendulum is swinging these days—from worst to first and then back again. When I get pitches from elected people, I never totally believe what they’re selling. The swings are a lot more wild and less predictable than we saw five to 10 years ago. … It’s less stable for a charter operator.”

CMOs noted the importance of multiple funders committed to high-quality CMO growth within a given region.

Charter authorization and governance factors that influence CMO decision-making.

CMOs seek a clear, efficient, and fair process for authorization and governance. If a CMO plans to open multiple schools in a new region, it wants its authorizer to give assurances—or at least clarity—about a path toward expansion. In the words of one CMO leader, “We don’t want local politics to get

in the way of obtaining our charters.” To make expansion worth the effort in terms of both impact and financial sustainability, CMOs generally seek regions in which they can attain authorization to open multiple schools.Most CMOs have a preference about authorizer options, seeking regions with either multiple authorizers or an independent (nondistrict) authorizer. While this sentiment is not universal—one respondent actually preferred a district authorizer—most respondents indicated that a fair, flexible authorizing process was an important consideration in their expansion decisions.

When creating their governance structure in a new region, CMOs prefer to have the freedom to organize their boards of directors in whatever way makes most sense to them. In most cases, this involves having a single regional (or even national) board rather than individual boards for each school or campus. CMO leaders reported that a centralized board structure makes it easier for CMOs to focus on their core work of educating children rather than trying to recruit and appease a plethora of different boards. CMOs avoid board composition requirements (e.g., a requirement to have all board members live within a certain geographic area). Such requirements, while usually well intentioned, often create an unwieldy governance structure for CMOs and may crowd out the members most able to hold the school accountable for executing on its mission.

The CMOs seek these conditions for the best of reasons — maximizing their probabilities of success — meaning success in educating their student population. There is competition among regions to attract the best practitioners.

Virginia needs to join and win in that competition. Governor-elect Youngkin is clearly dedicated to doing so. It will take a lot of bi-partisan work. No CMO will come here based on single party support because of the political risk.

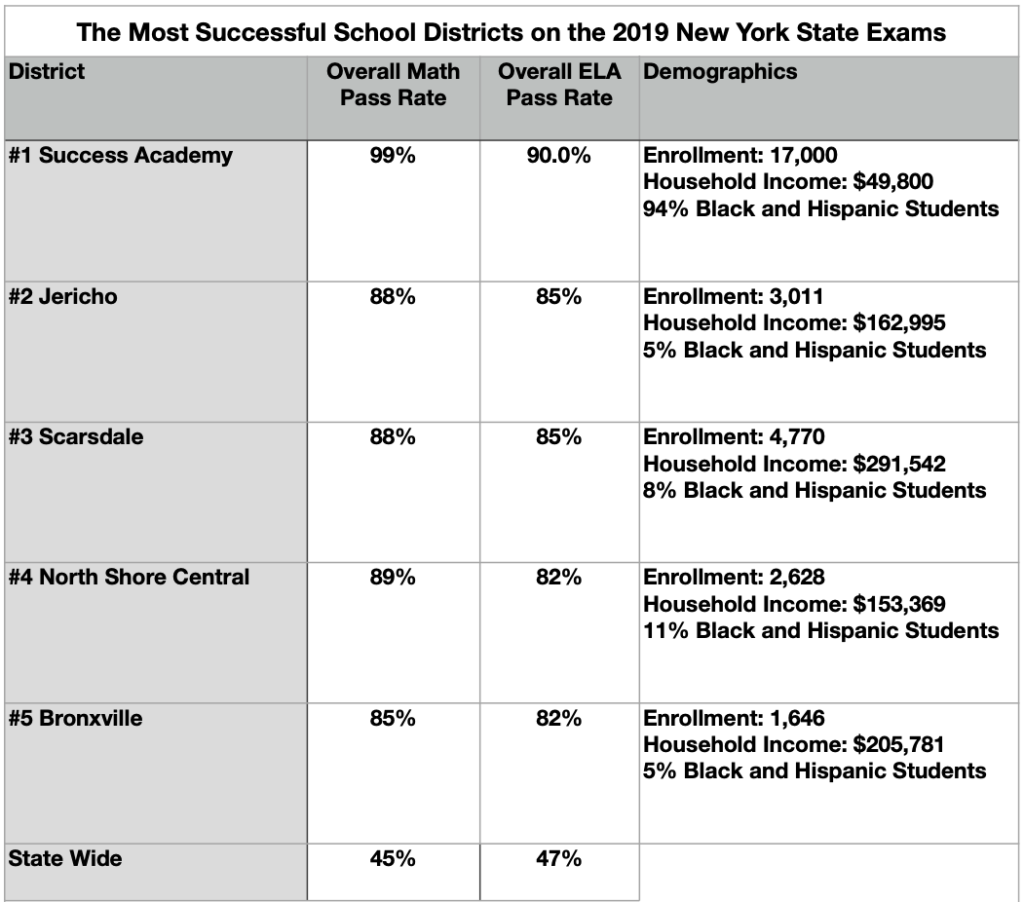

For the reason support should prove bi-partisan, I post again a chart from an earlier column.

The chart below posits the schools of Success Academy, a public charter management organization that educates thousands of children in New York City, as its own school district for purposes of comparison.

Any politician who opposes such results in Virginia raise your hand- and retire.