Source: Powerline blog

by James A. Bacon

In thinking about what ails Virginia’s K-12 public schools, perhaps we should give some consideration to the state’s schools of education and what Virginian teachers are taught. To get a sense of the quality of scholarship and thought that comes out of our teaching academies, we might consider an op-ed penned nine days ago for the Washington Post by Robert C. Pianta, dean of the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education and Development.

Here is the thesis of his piece: “The perception that education is in crisis has contributed a fundamentally distorted view of the system that ignores the biggest problem plaguing U.S. public schools: a lack of resources.”

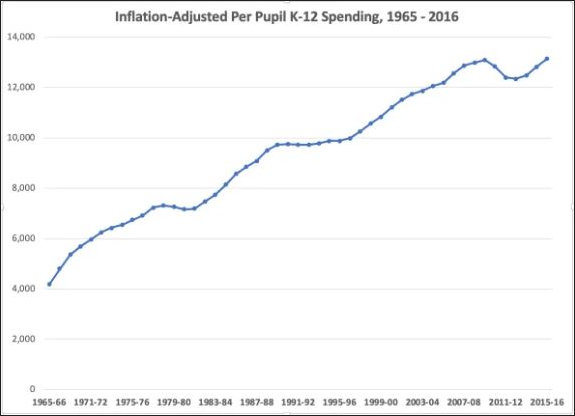

Sadly for Mr. Pianta, the op-ed now bears a correction at the top, which reads as follows: “An earlier version of this piece stated that, adjusting for constant dollars, public funding for schools had decreased since the late 1980s. This is not the case. In fact, funding at the federal, state and local levels has increased between the 1980s and 2019.”

The truth of the matter is that inflation-adjusted, per-pupil K-12 spending nationally reached a new peak in 2015-16, according to figures presented in the Powerline blog (and displayed above). Here in Virginia, while the state contribution to K-12 still falls short of its peak, the supposition that schools are starving for funds is driving Governor Ralph Northam’s proposal to funnel $1.2 billion more into K-12 in the next two-year budget.

But funding facts aside, is it accurate to say, as the Washington Post headline for Pianta’s op-ed suggests, “The one education reform that would really help? Giving public schools more money.”

In previous posts, I have demolished that widespread view by showing how schools in Southwestern Virginia used data, analytics and the sharing of best practices to boost Standards of Learning (SOL) pass rates last year even while other regions across Virginia, including those where school districts had far more money, fell.

Let me now buttress that case by presenting a close-up of the achievements of Washington-Lee Elementary School in the city of Bristol. I draw upon a narrative written by Keith Perrigan, superintendent of Bristol Public Schools, and forwarded to me by Frank Kilgore, a long-time advocate of SW Virginia schools.

Five years ago Washington-Lee was one of the lowest-performing schools in the state. The student population was predominantly white (69%) but it had significant minority population — 15% African American, 13% multiracial, 2% Hispanic and 1% Asian. Eighteen percent of students were classified as “special education,” and 95% qualified for free and reduced meal eligibility.

The Bristol school system designated the elementary school as a “Focus School” and appointed a new principle to transform the institution. Writes Perrigan: “WL has progressed from the bottom 10% of standardized test scores in Virginia to the top 13th percentile of schools based on performance on state learning standards.”

How did this transformation take place? The school utilized data to guide instructional efforts, identify when students were encountering problems, and provide extra help as needed.

This success is a result of constant reflection on student data and monitoring of student progress. Monthly RTI meetings are held in both math and reading. Instructional coaches lead these meetings and current student data is analyzed, interventions planned and monitored, and other factors impacting student success are examined so that necessary supports can be put in place. …

Guided Reading strategies allowed a deeper view of individual students’ reading abilities so that teacher could get to the root of students’ struggles. The process required individual assessment of students to establish each child’s reading level. Reading materials were purchased that enabled teachers to instruct every student on his/her individual level. …

Math classes have adopted small group settings as a regular practice. … Teachers have begun practicing Universal Design for Learning. … Lesson objectives are clearly expressed and posted so that students understand the daily learning goals. … The most productive feature is the frequent, specific feedback given to students as they work. …

Under the Comprehensive Instructional Program (CIP), school districts in Southwest Virginia have collaborated for several years to use data to identify and share best practices. The strategy has been so successful that other rural schools have joined the consortium. Alas, this extraordinary progress appears to have penetrated the worldview of the politicians and educrats in Richmond, whose solution, like Pianta’s, is to dump more money into failing school systems without making any structural changes.

Perhaps the dean of Virginia’s most prestigious school of education could rethink his critique, which blames standardized tests and school under-funding, and advocates mo’ money for pretty much everything. Perhaps the Curry School could learn something from the education revolution occurring in Southwest Virginia. Here’s a wild thought: Perhaps the Curry School could even join the CIP collaboration, lend its expertise, propagate best practices to other Virginia schools, and — dare I say it? — teach its own students! Of course, that might require Pianta to ditch everything he knows (or thinks he knows) about education in America and start from scratch, so I’m not expecting that to ever happen.