Each day I wake up and tell myself, “I’m not going to write about race today. I’m tired about writing about race. I want to write about something else.” But each day I read the Richmond Times-Dispatch and Washington Post, and each day there are articles and op-ed columns about race, almost all of which perpetuate the narrative of endemic racism in America today. Of course racism still exists, and of course people of good will need to stand against it. But America is not a endemically racist society, and Virginia is not an endemically racist commonwealth. I have no choice but to counter a pernicious and destructive falsehood.

The latest offense comes from Kristen Amundson, a former member of Virginia’s House of Delegates and, scarily, a former chair of the Fairfax County School Board. Virginia has a lot to learn about race, she writes in the Times-Dispatch, and schools are a good place to start. She makes numerous assertions that warrant response, but I will focus on the most egregious and show how it harms the very kids she purports to care about.

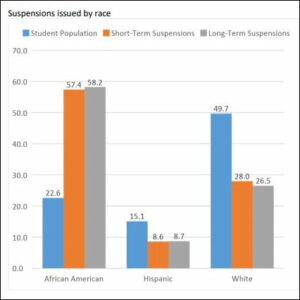

In the op-ed Amundson contends that Virginia should “ensure that students of color are not suspended for minor misbehavior” (my emphasis). In Virginia, black students are more likely than their white peers to be suspended, even for minor violations, she says. Citing the Legal Aid Justice Center, she notes that black students were suspended at rates five times higher than Hispanics and whites last year. The gap was significantly higher than it had been the previous year.

Some obvious questions occur. Blacks are suspended at a higher rate than whites and Hispanics. In other words, Hispanics, who generally fall under the rubric of people “of color” are suspended at almost the same rate as whites, according to the Justice Center’s own data (displayed in the graph above).

Amundson implies that Virginia’s racist institutions discriminate against all “people of color,” yet Hispanic people of color are punished at the same rate as whites. Why would this be? Could it be that the putative racism in Virginia schools does not extend to this particular sub-set of brown people? Is it possible that blacks are suspended at higher rates because they commit more offenses? Is it possible that, continually bombarded by the message (from people like Amundson) that they are victims of racism, black students have less respect for school authority and are more oppositional in their behavior? Is it possible that blacks, who are more likely to grow up in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty and in fatherless households, are subject to less discipline at home and, thus, are more resistant to discipline at school? Is it possible that black teenagers, perceiving the reluctance of school authorities to discipline blacks, are exploiting that reluctance?

Amundson implies that it is an indictment of Virginia’s education system that the gap in black and white discipline has widened in the past year — yet she neglects to mention that this trend occurred even while Social Justice-driven disciplinary policies have been implemented at more schools. Teachers and principals are employing a more therapeutic approach to disciplinary infractions for the explicit purpose of reducing the racial gap — yet the racial gap has gotten wider. Remarkably, Amundson shows no sign of cognitive dissonance.

Nor does her op-ed refer to disparities in the very school district of which she served as school board chair. According to the Legal Aid Justice Center, Fairfax County issued long-term suspensions to 4.65% of its black students at least once last year, compared to a mere 0.96% of its white students — almost five times more frequently! Are Amundson’s colleagues in Fairfax County racist? Is the school system over which she presided permeated with unconscious institutional racism? If so, it is curious that she did not tackle these injustices when she was in a position to do something about them.

Amundson does not consider alternative explanations of disciplinary disparities. To her way of thinking, evidence of disparity is proof of discrimination.

Worse, while Amundson and the Legal Aid Justice Center bemoan the suspensions and other punishments meted out to misbehaving students, they express no concern about the students whose teaching is disrupted by classroom misbehavior, the fact that students whose classes are disrupted are disproportionately black themselves, or the fact that racial disparities in SOL test scores last year also got worse — arguably a direct result of deteriorating classroom discipline.

Social Justice Warriors have a narrative of racial injustice, and, by god, they’re sticking to it. Maybe it’s true that students suspended from school find it harder to catch up academically. Maybe it’s true that Virginia’s disciplinary policies should be improved. But don’t blame those problems on racism. Oblivious to unintended consequences, Social Justice Warriors are making racial disparities in Virginia schools worse, not better.