Source: “Operations and Performance of the Virginia Employment Commission, 2021,” Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission

by James A. Bacon

By way of preface, let us acknowledge that managerial problems at the Virginia Employment Commission preceded the Northam administration. And let us acknowledge that the magnitude of the challenge in responding to the unemployment spike during the COVID-19 epidemic was unprecedented. It would not be fair to blame the entirety of the VEC’s breakdown in performance — one of the worst in the country — upon the ineffectual leadership of Governor Ralph Northam. But it is entirely defensible to say that the VEC’s spectacular failure to expedite unemployment claims was one of the most consequential failures of his tenure.

Team Northam was both slow and lacking in its response to VEC’s challenges. Not only did the agency’s inability to process unemployment insurance claims create hardship for hundreds of thousands of out-of-work Virginians who went months without their checks, it engendered ancillary crises downstream such as the spike in tenant evictions and the turmoil resulting from that. VEC’s failure added immeasurably to COVID-related misery in Virginia,

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) does not draw those conclusions in its recently published report dissecting VEC’s performance during the pandemic, but the inference is unavoidable. Here is what JLARC did say:

Some of the most impactful executive actions by VEC leadership that would have helped VEC respond to the surge in UI claims were delayed over a year into the pandemic. Taking certain actions earlier in the pandemic — especially those related to staffing increases and IT system improvements — may have helped VEC respond more effectively to the increased UI claims volume and program challenges.

VEC also could have benefited from additional oversight and assistance from the administration and could have better availed itself of expertise and resources in other areas of state government.

JLARC makes clear that problems at VEC preceded the Northam administration. The report refers to “significant weaknesses in VEC’s operations,” including deficient staffing levels and an antiquated IT system, both of which were revealed by the epidemic. After trying to modernize its IT system for 12 years, the agency is eight years behind. Delays in modernizing the IT system meant VEC relied on outdated, manual processes that led to persistent inefficiencies. Lacking a customer-facing portal, for instance, the legacy system forced customers to rely on call centers and physical mail. VEC employees had to process claims manually. Lacking automated data analytics, the legacy system also makes it difficult to sniff out “inaccurate or fraudulent benefit programs.”

Under fire, VEC blamed its low operational efficiency on insufficient funding. However, JLARC noted that federal funding, the main funding source for the program, in 2019 was above the 50-state media in total and per claim. Moreover, JLRC found, VEC was top-heavy with administrative staff.

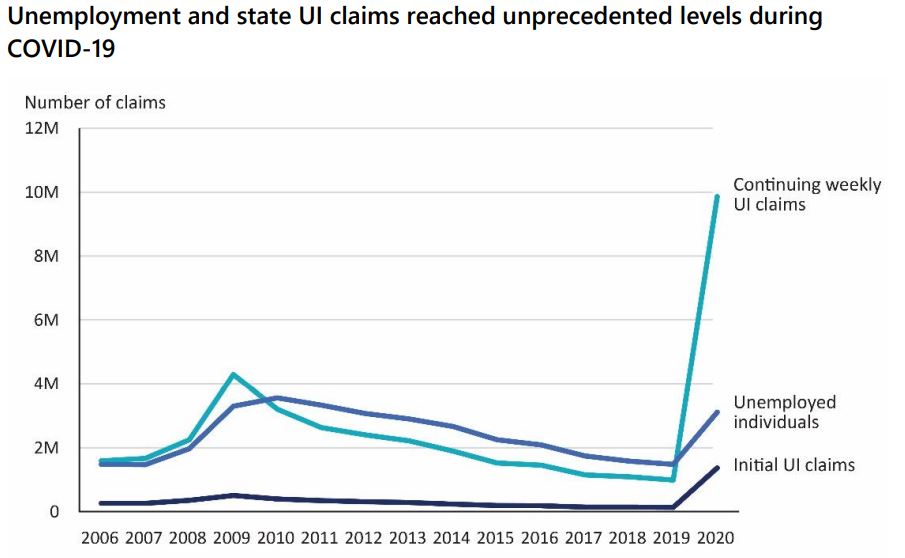

Partly as a consequence of these ongoing deficiencies, when COVID-19 shutdowns caused widespread unemployment– the volume of claims increased by a factor of 24 within the first two months of the epidemic — the VEC system was overwhelmed. When the epidemic hit, the number of unemployed individuals leaped from 117,000 in February 2020 to 482,000 in April. The number of calls to its call centers shot from about 100,000 monthly to more than 3 million.

One could say that the Northam administration was dealt a bad hand… and played it badly.

Despite the manifestly evident shortages of manpower, notes JLARC, VEC responded sluggishly. While other states quickly brought on contractors to back up their unemployment agencies, Virginia didn’t hire contractors

- to assist with the initial claims intake until November 2020,

- to assist with adjudication until May 2021, or

- to help process a backlog of 580,000 employer separation reports until August 2021.

At one point last year, Virginia ranked as the worst state in the country for processing unemployment claims. Even now, a year and a half after the epidemic struck, uncompleted claims continues to grow, JLARC says. In May VEC estimated that its staff had approximately 2 million claims “issues” still to review, about one million of which might require adjudication.

JLARC also estimates that VEC might have paid an estimated $930 million in benefits incorrectly, plus another $322 million in the first half of this year. VEC’s estimated rate of fraud increased from 1.4% of payments to 7.5% as VEC dispensed with investigations and fact-finding to move claims more quickly.

What could Virginia have done differently? JLARC points to the example of other states:

- Utah largely avoided a UI claims backlog because it has a modernized IT system that allows customers to upload required documents online and check the status of claims without the necessity of calling a call center.

- Maryland was close to completing its IT modernization when COVID-19 started. Rather than pausing the project, Maryland launched the new system in 2020, allowing it to process claims more quickly.

- New Jersey improved responsiveness to customer calls by hiring over 200 third-party contractors to assist with its call center.

- North Carolina added 1,800 call center agents, reducing average hold times to less than a minute. It also increased overall agency staffing from 500 employees to more than 2,500, allowing it to process more than 100,000 backlogged claims by September 2020.

Team Northam didn’t create VEC’s mess, but it flailed ineffectually in dealing with it. The inability to process unemployment claims — submitted disproportionately by the poor minorities whose jobs were more likely to be impacted by the shutdowns — should have been flagged immediately. And when VEC’s top brass proved incapable of getting a handle on the problem, heads should have rolled. After botching the COVID vaccine rollout, in which Virginia ranked nearly worst in the country for the rate of vaccinations, the administration appointed Danny Avula as the vaccine czar to cake charge, and Avula got results. Nothing of the sort happened with VEC.

Indeed, Northam administration officials were part of the problem. JLARC notes that VEC tried to obtain an emergency exemption from state hiring requirements from “cabinet officials” in April 2020 — was this a veiled referenced to Secretary of Labor Megan Healey? — but the request was not granted. Without the exemption, VEC was hindered in its ability to increase call center staff. VEC also requested staff from other agencies be assigned to it temporarily, but the other agencies objected, and no one in the administration overrode them.

As recently as May 2021, VEC was still trying to figure out ways to increase staffing by borrowing employees from other agencies. Northam issued Executive Directive 16 ordering VEC to “coordinate with” the Virginia Department of Human Resource Management to identify employees in other agencies who could fill in. But there was no follow through. Of the two options VEC advanced, neither approved acceptable to other agencies. Says JLARC: “Both of these strategies and several others were not pursued.