This is a copy of a speech that I presented to the Virginia Chapter of the American Planners Association Monday, with extemporaneous amendments and digressions deleted. — JAB

Thank you very much, it’s a pleasure to be here. Urban planning is a fascinating discipline. As my old friend Ed Risse likes to say, urban planning isn’t rocket science – it’s much more complex. Planners synthesize a wide variety of variables that interact in unpredictable, even chaotic, ways. In my estimation, you don’t get nearly enough respect and appreciation for what you do

OK, enough with the flattery. Let’s get down to business.

This is you. You’re toast. Unless you change the way you do things, you and the local governments across Virginia you represent are totally cooked. … Here’s what I’m going to do today. I’m going to tell you why you’re toast. And then I’m going to tell you how to dig your government out of the fiscal abyss, earning you the love and admiration of your fellow citizens.

This is you. You’re toast. Unless you change the way you do things, you and the local governments across Virginia you represent are totally cooked. … Here’s what I’m going to do today. I’m going to tell you why you’re toast. And then I’m going to tell you how to dig your government out of the fiscal abyss, earning you the love and admiration of your fellow citizens.

Why You’re Toast

Here’s the first reason you’re in trouble — old people. Or, more precisely, retired government old people. Virginia can’t seem to catch up to its pension obligations. The state says the Virginia Retirement System is on schedule to be fully funded by 2018-2020. But the state’s defines 80% funded as “fully funded,” which leaves a lot of wiggle room. The VRS also assumes that it can generate 7%-per-year annual returns on its $66 billion portfolio. For each 1% it falls short of that assumption, state and local government must make up the difference with $660 million. As long as the Federal Reserve Board pursues a near-zero interest rate policy, depressing investment returns everywhere, that will be exceedingly difficult. A lot of very smart people think 5% or 6% returns are more realistic. In all probability, pension obligations will continue to be a long-term burden on localities.

Here’s the first reason you’re in trouble — old people. Or, more precisely, retired government old people. Virginia can’t seem to catch up to its pension obligations. The state says the Virginia Retirement System is on schedule to be fully funded by 2018-2020. But the state’s defines 80% funded as “fully funded,” which leaves a lot of wiggle room. The VRS also assumes that it can generate 7%-per-year annual returns on its $66 billion portfolio. For each 1% it falls short of that assumption, state and local government must make up the difference with $660 million. As long as the Federal Reserve Board pursues a near-zero interest rate policy, depressing investment returns everywhere, that will be exceedingly difficult. A lot of very smart people think 5% or 6% returns are more realistic. In all probability, pension obligations will continue to be a long-term burden on localities.

Second, the infrastructure Ponzi scheme — that’s Chuck Marohn’s coinage, not mine — is catching up with us. For decades, state and local government built roads and infrastructure, typically with federal assistance, proffers or impact fees with no thought to full life-cycle costs. State and local governments have assumed responsibility for maintaining and replacing this infrastructure. Well, the life cycle done cycled, and the bill is coming due. We’re finding that we built more infrastructure than we can afford to maintain at current tax rates, leaving very little for new construction.

Second, the infrastructure Ponzi scheme — that’s Chuck Marohn’s coinage, not mine — is catching up with us. For decades, state and local government built roads and infrastructure, typically with federal assistance, proffers or impact fees with no thought to full life-cycle costs. State and local governments have assumed responsibility for maintaining and replacing this infrastructure. Well, the life cycle done cycled, and the bill is coming due. We’re finding that we built more infrastructure than we can afford to maintain at current tax rates, leaving very little for new construction.

Third, after years of delay, serious storm water regulations are kicking in. Local governments bear responsibility for fixing broken rivers and streams like Accotink Creek, showed here. (Yeah, that’s a creek. It’s having a bad day.) Best guess: These regs will cost Virginia another $15 billion. But no one really knows. And it may just be the tip of the iceberg. I recently talked to Ellen Dunham-Jones, author of “Retrofitting Suburbia,” and she noted that a lot of the storm water infrastructure that developers built in the ‘50s and ‘60s is crumbling. The developers are long gone. Someone’s going to have to fix that, too. Guess who?

Third, after years of delay, serious storm water regulations are kicking in. Local governments bear responsibility for fixing broken rivers and streams like Accotink Creek, showed here. (Yeah, that’s a creek. It’s having a bad day.) Best guess: These regs will cost Virginia another $15 billion. But no one really knows. And it may just be the tip of the iceberg. I recently talked to Ellen Dunham-Jones, author of “Retrofitting Suburbia,” and she noted that a lot of the storm water infrastructure that developers built in the ‘50s and ‘60s is crumbling. The developers are long gone. Someone’s going to have to fix that, too. Guess who?

Meanwhile, the largest source of discretionary local tax dollars – real estate property tax revenues – is stagnating. According to the Demand Institute, residential real estate prices in Virginia will increase only 7% through 2018 – the third worst performance of any state in the nation. Don’t count on magically rising property tax revenues to bail you out.

Meanwhile, the largest source of discretionary local tax dollars – real estate property tax revenues – is stagnating. According to the Demand Institute, residential real estate prices in Virginia will increase only 7% through 2018 – the third worst performance of any state in the nation. Don’t count on magically rising property tax revenues to bail you out.

In fact, the tax situation is worse than it looks. Demand for commercial real estate is dismal, too. Consider what’s happening to the retail sector. We’re going from this…

Every Amazon.com distribution center represents dozens if not hundreds of chain stores closing. It means more vacant store fronts, more deserted malls, less new retail development.

Don’t look for help from new office space. Due to the rise of the mobile workforce, 50% of the desks, cubicles and offices in commercial buildings are vacant at any given time. Corporate America can – and will – save billions by downsizing their office portfolios. I recently heard one Washington, D.C., official refer to it as the “compression” of office space. He predicted that businesses will get by with 20% less space. As leases roll over, millions of square feet of office space will dump onto the market. Commercial real estate property values will stay depressed.

Don’t look for help from new office space. Due to the rise of the mobile workforce, 50% of the desks, cubicles and offices in commercial buildings are vacant at any given time. Corporate America can – and will – save billions by downsizing their office portfolios. I recently heard one Washington, D.C., official refer to it as the “compression” of office space. He predicted that businesses will get by with 20% less space. As leases roll over, millions of square feet of office space will dump onto the market. Commercial real estate property values will stay depressed.

Finally, you’re dreaming if you think industrial recruitment will bail you out. There may be a manufacturing renaissance in America but most of the investment is going to increasing productivity of existing plants rather than building new plants. Other than industries that feed off cheap and abundant natural gas – mostly along the Gulf Coast — the U.S. will see fewer greenfield plant expansions than in years past. … Admittedly, no sooner had I written these words in my rough draft then a Chinese paper company announced a $2 billion investment in Chesterfield County. OK, Chesterfield won the mega-million jackpot. Congratulations, Chesterfield! The rest of you won’t be so lucky.

Finally, you’re dreaming if you think industrial recruitment will bail you out. There may be a manufacturing renaissance in America but most of the investment is going to increasing productivity of existing plants rather than building new plants. Other than industries that feed off cheap and abundant natural gas – mostly along the Gulf Coast — the U.S. will see fewer greenfield plant expansions than in years past. … Admittedly, no sooner had I written these words in my rough draft then a Chinese paper company announced a $2 billion investment in Chesterfield County. OK, Chesterfield won the mega-million jackpot. Congratulations, Chesterfield! The rest of you won’t be so lucky.

The bottom line is this: If we continue doing the same thing the same way, all is lost. The prosperity model that worked for Virginia in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s is not working any more. If it’s any consolation, it’s not working anymore anywhere, not just Virginia.

The bottom line is this: If we continue doing the same thing the same way, all is lost. The prosperity model that worked for Virginia in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s is not working any more. If it’s any consolation, it’s not working anymore anywhere, not just Virginia.

An immense competitive advantage will go to those who reinvent themselves first. Fortunately, the early 21st century just might be the most exciting time ever to be involved in local government. Two broad strategies can make a huge difference if localities choose to adopt them… and the planning profession is positioned to play a pivotal role in making sure that they do.

An immense competitive advantage will go to those who reinvent themselves first. Fortunately, the early 21st century just might be the most exciting time ever to be involved in local government. Two broad strategies can make a huge difference if localities choose to adopt them… and the planning profession is positioned to play a pivotal role in making sure that they do.

Smart Cities

The first strategy falls under the rubric of Smart Cities – the application of information technology and communications to deploy sensors, collect vast amounts of data, store it on the cloud, and analyze it for far less than anyone imagined was possible a few years ago. That data can be used to cut costs, guide decision making and engage the citizenry.

The first strategy falls under the rubric of Smart Cities – the application of information technology and communications to deploy sensors, collect vast amounts of data, store it on the cloud, and analyze it for far less than anyone imagined was possible a few years ago. That data can be used to cut costs, guide decision making and engage the citizenry.

Some investments are no brainers and there is no excuse not to make them. Smart street lights can cut lighting costs by 50%. Smart pipes can reduce water leakage by 20%. Building automation in municipal buildings can generate energy savings of 30% to 40%. Admittedly, those are investments that the Public Works department should be pushing for. But other smart-cities investments will never be made unless planners make the case for them.

For example: Variable priced parking. Here’s a picture of Jay Primus, manager of SFPark in San Francisco, who I visited back in April. Using smart meters and adjusting prices to reflect localized supply and demand conditions allowed San Francisco to reduce average parking prices, ensure that parking spaces were almost always open, reduce the number of people cruising around looking for parking, and generally make the city a more hospitable place to do business. Interestingly, San Francisco regards smart parking as an economic development initiative. Virginia planners should be pushing for this tool.

Another example: Traffic management. The cost is dropping to equip traffic lights with sensors, link them to a central control facility, and change the  lighting sequences dynamically in response to traffic conditions. This is not a cure-all for traffic congestion but it can delay the necessity for undertaking super-expensive ROW acquisitions and construction projects. Virginia planners should be agitating for this technology.

lighting sequences dynamically in response to traffic conditions. This is not a cure-all for traffic congestion but it can delay the necessity for undertaking super-expensive ROW acquisitions and construction projects. Virginia planners should be agitating for this technology.

Smart Growth

The second big strategy falls under the rubric of smart growth, although you also could call it fiscally disciplined growth. The labels are unimportant. What matters is understanding the fiscal implications of different patterns of development. It is axiomatic that denser, more compact growth requires less supporting infrastructure than scattered, low-density growth. Undertaking fiscally disciplined growth won’t balance your budget tomorrow but it will pay huge dividends year after year, pretty much forever. Just look at Arlington County, which has stuck to the strategy for 40 years. Arlington has done such a superior job with its transportation and land use policies its supervisors can afford to indulge in such questionable niceties as million-dollar bus stops and $30 million natatoriums.

The second big strategy falls under the rubric of smart growth, although you also could call it fiscally disciplined growth. The labels are unimportant. What matters is understanding the fiscal implications of different patterns of development. It is axiomatic that denser, more compact growth requires less supporting infrastructure than scattered, low-density growth. Undertaking fiscally disciplined growth won’t balance your budget tomorrow but it will pay huge dividends year after year, pretty much forever. Just look at Arlington County, which has stuck to the strategy for 40 years. Arlington has done such a superior job with its transportation and land use policies its supervisors can afford to indulge in such questionable niceties as million-dollar bus stops and $30 million natatoriums.

In an era of chronic fiscal stress, roads, utilities, public facilities and otter infrastructure are major drivers of local government spending. Local government financial officers lack the analytical tools to guide growth decisions. But those tools are out there – planners need to use them.

In an era of chronic fiscal stress, roads, utilities, public facilities and otter infrastructure are major drivers of local government spending. Local government financial officers lack the analytical tools to guide growth decisions. But those tools are out there – planners need to use them.

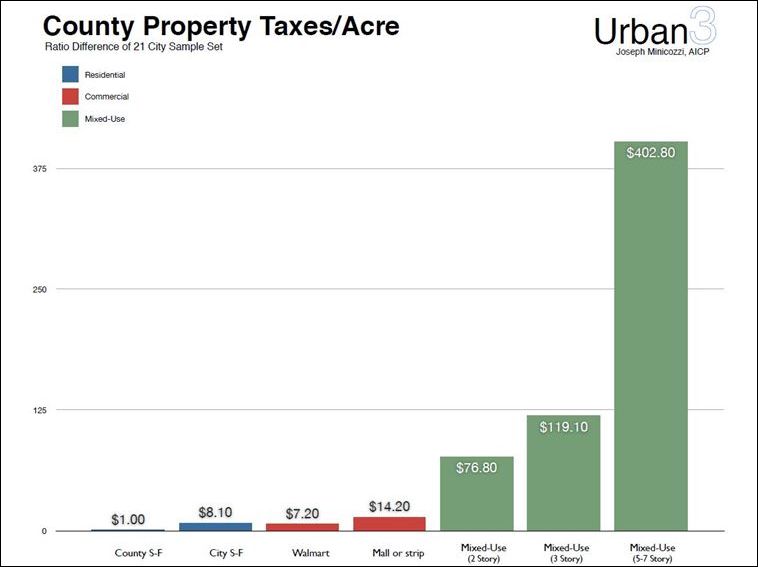

Joe Minicozzi and Peter Katz conducted a famous study in Sarasota, Fla., comparing the real estate tax yield per acre of different types of development. The findings were mind-boggling: Mid-density, mixed-use development yielded 50 to 100 times the property tax per acre of a new Wal-Mart. At the same time, the cost of providing infrastructure for compact development can be cheaper per acre. Compared to conventional suburban development, according to Smart Growth America, fiscally efficient development can save 38% in up-front infrastructure costs and 10% of the cost of supporting police, ambulance, fire and other public services.

Joe Minicozzi and Peter Katz conducted a famous study in Sarasota, Fla., comparing the real estate tax yield per acre of different types of development. The findings were mind-boggling: Mid-density, mixed-use development yielded 50 to 100 times the property tax per acre of a new Wal-Mart. At the same time, the cost of providing infrastructure for compact development can be cheaper per acre. Compared to conventional suburban development, according to Smart Growth America, fiscally efficient development can save 38% in up-front infrastructure costs and 10% of the cost of supporting police, ambulance, fire and other public services.

Sarasota was not a fluke. The slide above comes from Joe Minicozzi who has compiled these numbers from a sample of 21 jurisdictions. Mixed-use development yields 20 to 40 times more revenue per acre than Walmarts and shopping malls, and 400 times that of low-density single-family dwellings. Higher revenues per acre, lower costs per acre – you can’t beat that combination. The single most important thing you can do to survive hard fiscal times is to promote in-fill and re-development at higher density than existing land uses and maximize utilization of the infrastructure already on the ground.

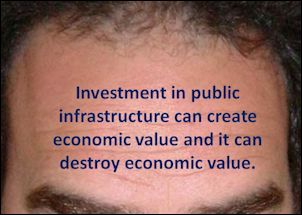

Now, let’s talk about the second most important thing you can do. Tattoo this on your forehead so you can see it every day when you look in the mirror:

To pick an obvious example, highway interchanges like this one in Fredericksburg create economic value in nearby land, as measured by real estate property assessments.

To pick an obvious example, highway interchanges like this one in Fredericksburg create economic value in nearby land, as measured by real estate property assessments.

Metro stations like this one in Arlington create economic value.

Parks, even small ones like this one in Richmond, create economic value.

Parks, even small ones like this one in Richmond, create economic value.

Bike lanes create economic value.

Bike lanes create economic value.

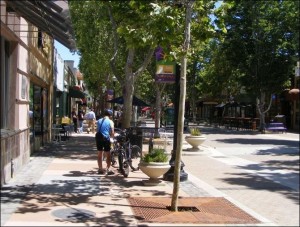

Walkable, bikable, people-friendly “complete streets” create incredible economic value. People are willing to pay incredible premiums to live, work in play in places like this, as opposed to…

Places like this…

Stroads like this one destroy economic value. Stroads are street-road hybrids. They do a worse job than roads of moving cars and they do a worse job than streets of creating places where people like to live, work and shop. Most stroads in Virginia can be found along old state and national highways. They arose as businesses began using them as de-facto main streets and local governments failed to limit access and protect their integrity as highways. They are neither walkable nor drivable, and they will take billions of dollars to fix. Sadly, this pattern of wealth destruction is endemic across Virginia. By permitting this stuff, we are running our communities into the ground. A number of counties have created ambitious plans to “revitalize” old, decaying segments of these corridors but I can promise you, unless you convert them into people-friendly streets, you are totally wasting your time.

Putting a tutu on a pig does not make him a ballerina.

Putting a tutu on a pig does not make him a ballerina.

Toward a New Fiscal Analytics

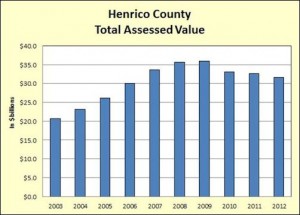

This question is fundamental: Are zoning codes and capital investment plans in your city or county creating taxable wealth or destroying it? There’s a key metric that every planner needs to know about their jurisdiction — total assessed value of real property. Do you know how the total assessed value of your jurisdiction? A senior planner not knowing the answer to that question is like a Chief Financial Officer of a corporation being unable to tell you how much revenue his company generates. How can he possibly do his job?

I pulled the numbers for Henrico County where I live. The number was about $32 billion in 2012. Admittedly, this is a crude measure. Total assessed value is influenced by things out of your control like interest rates, housing trends and economic conditions. But it is still a useful proxy for how good a job you’re doing at running your city or county. If you pursue policies that create wealth, homeowners and businesses will invest more in maintaining their properties, and new enterprises will expand, and property values will rise. If you create places that people shun, your property values will decline.

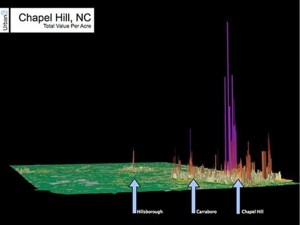

Let’s take a closer look. It’s possible to display assessed property values graphically in ways that convey an awful lot of information. This map from Joe Minicozzi shows Orange County, N.C. The spikes represent taxable real estate value per acre. Look at the difference between Chapel Hill, Carrboro and Hillsboro. Sure, Chapel Hill has a big advantage over the other two because the University of North Carolina sits right in the middle. But the town also has permitted development at higher densities that throw off lots of tax revenue without a lot of offsetting liabilities. Do you know where the spikes are in your city or county? Can you tell if any given property is a net contributor or drain on the tax base? Do you know where property values are increasing in your jurisdiction and where they are declining? Can you predict the impact – pro or con – of public investments on the local tax base?

Cities and counties have finite resources to invest in public projects. You don’t have the luxury of throwing money away. It is imperative that you analyze the fiscal return on investment – how a capital expenditure will impact the assessed value of real estate and the revenue it throws off vs. the expense you will incur to maintain infrastructure on a full life-cycle basis. Without this data, you cannot possibly make informed decisions.

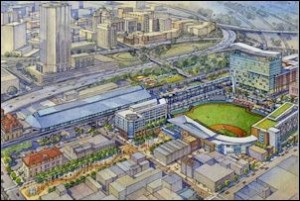

Perhaps you’re familiar with the minor league baseball stadium proposed for the Shockoe Bottom neighborhood of the City of Richmond. Mayor Dwight Jones wants to invest $80 million in public funds to build a stadium and parking deck, contribute towards a slavery museum, and install flood control infrastructure. He argues that the project will “pay for itself” by stimulating commercial and residential development around it. City Council is not convinced. Neither side can make a fully convincing case and the result is a stand-off in which nothing gets done. In all the hoopla, however, there is one question no one is asking – is this the best expenditure of $80 million that the city can come up with? When you spend $80 million on Project A, you cannot spend it on Project B. Can Richmond get more bang for its buck developing the riverfront? Or creating complete streets? Or building bike lanes? Or investing in Bus Rapid Transit? Or building a new stadium at the current site? We simply don’t know because the city has no methodology for comparing Return on Investment on different projects. We’re fumbling in the dark.

Perhaps you’re familiar with the minor league baseball stadium proposed for the Shockoe Bottom neighborhood of the City of Richmond. Mayor Dwight Jones wants to invest $80 million in public funds to build a stadium and parking deck, contribute towards a slavery museum, and install flood control infrastructure. He argues that the project will “pay for itself” by stimulating commercial and residential development around it. City Council is not convinced. Neither side can make a fully convincing case and the result is a stand-off in which nothing gets done. In all the hoopla, however, there is one question no one is asking – is this the best expenditure of $80 million that the city can come up with? When you spend $80 million on Project A, you cannot spend it on Project B. Can Richmond get more bang for its buck developing the riverfront? Or creating complete streets? Or building bike lanes? Or investing in Bus Rapid Transit? Or building a new stadium at the current site? We simply don’t know because the city has no methodology for comparing Return on Investment on different projects. We’re fumbling in the dark.

In Arlington County, there’s a huge controversy over construction of a $360 million streetcar line on Columbia Pike. Supporters say the project will pay for itself by increasing property values and bolstering investment along Columbia Pike. Foes question that argument. People on both sides of the debate tend to believe whatever they want to believe and can’t be convinced otherwise. Maybe the street car line will pay its own way, I don’t know. But Arlington faces a bigger question that nobody seems to be asking: Is this really the best investment of finite tax dollars compared to alternatives, either a different mega-project or broken up as a lot of smaller projects? Would $360 million generate higher returns elsewhere? Arlington planners, as savvy as they are in many ways, cannot answer that question.

In Arlington County, there’s a huge controversy over construction of a $360 million streetcar line on Columbia Pike. Supporters say the project will pay for itself by increasing property values and bolstering investment along Columbia Pike. Foes question that argument. People on both sides of the debate tend to believe whatever they want to believe and can’t be convinced otherwise. Maybe the street car line will pay its own way, I don’t know. But Arlington faces a bigger question that nobody seems to be asking: Is this really the best investment of finite tax dollars compared to alternatives, either a different mega-project or broken up as a lot of smaller projects? Would $360 million generate higher returns elsewhere? Arlington planners, as savvy as they are in many ways, cannot answer that question.

Local government finance departments aren’t set up to deal with these issues. Basically, they’re bean counters. Their job is to balance the budget. Public works departments can’t do this either – they’re engineers focused on cost. Someone in local government has to ask the higher-order questions that are, by their nature, inter-disciplinary in scope. You planners are best equipped to do this. If you don’t ask these questions, no one else will. If you do ask those questions, and if you develop the tools it takes to answer them, you will dominate the local government decision-making process. Remember, information is power. If you have the information, you will have the power. You will set the agenda. Everyone will look to you to dig local governments out of their fiscal holes. You can be the heroes. Go for it!

Local government finance departments aren’t set up to deal with these issues. Basically, they’re bean counters. Their job is to balance the budget. Public works departments can’t do this either – they’re engineers focused on cost. Someone in local government has to ask the higher-order questions that are, by their nature, inter-disciplinary in scope. You planners are best equipped to do this. If you don’t ask these questions, no one else will. If you do ask those questions, and if you develop the tools it takes to answer them, you will dominate the local government decision-making process. Remember, information is power. If you have the information, you will have the power. You will set the agenda. Everyone will look to you to dig local governments out of their fiscal holes. You can be the heroes. Go for it!