by James A. Bacon

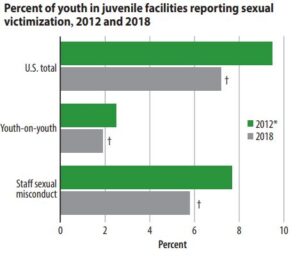

According to the late 2018 National Survey of Youth in Custody, an estimated 7.1% of youth held in juvenile facilities reported being “sexually victimized” during the previous 12 months.

The good news, such as is it, was that the percentage for Virginia youth was somewhat lower: 5.1% (subject to a fairly wide statistical margin of error). Another silver lining: The rate of rate of sexual victimization had declined from 9.5% since the previous survey in 2012.

The bad news, of course, is that any sexual victimization of young people in state facilities is unacceptable.

This data was brought to my attention by Rise for Youth, an organization dedicated to “dismantling the youth prison model” and promoting community-based alternatives to youth incarceration. As Executive Director Valerie Slater wrote in January in ACLU Virginia, Virginia’s criminal justice system is “deeply flawed” and stacked against “black, brown and poor men, women and youth.”

The majority of crimes for which juveniles are prosecuted are robbery and larceny, she writes. “When children are not given the resources they need to thrive, and youth perpetuate the cycles of violence and trauma they have seen and lived in their disenfranchised communities, our response must not be to intensify sanctions but rather to meet the needs.”

If sexual victimization is rampant in Virginia’s juvenile correctional facilities, that certainly would constitute an argument for doing away with them. So, let’s take a closer look at the numbers.

In 2018 the U.S. Department of Justice published a special report, “Sexual Victimization Reported by Youth in Juvenile Facilities, 2018,” based on 6,049 interviews with youth nationally. The Virginia sample of 276 youths from seven facilities responding to the survey was heavily influenced by the Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center in the Richmond metropolitan area, where 202 youths responded. So, reader be cautioned, the Virginia statistics are far more reflective of conditions at Bon Air rather than the state as a whole.

The first question we should address is this: What constitutes “sexual victimization.” The survey’s definition is far more expansive than rape or sexual assault. It includes:

- kissing on the lips

- kissing another body part

- being shown something sexual, such as pictures or a movie

- “other sexual activity,” such as looking at body parts.

Nationally, 5.8% of the young people who reported being victimized said they were forced or coerced by staff members, 1.9% by other youth.

The crucial unanswered question is whether the rate of sexual victimization, as defined by the survey, is higher or lower than in society at large? Put another way, are children safer or more at risk than if they were living at home?

Sadly, sexual assault and misbehavior is widespread in American society — in schools, in colleges, at the hands of priests — all the more so in dysfunctional households with single mothers, absentee fathers, transient live-in boyfriends, and unsupervised children.

According to RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), in FY 2016, child protective services agencies found strong evidence to indicate that more than 57,000 children were victims of sexual abuse nationally. One in nine girls and one in 53 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault at the hands of an adult. And that doesn’t include the exploitation of younger children by older juveniles.

It is entirely possible that children are safer from sexual abuse in juvenile correctional facilities than the environments they came from. We don’t know. Virginians should not be satisfied until sexual victimization at the hands of correctional staff is zero. (I doubt we’ll ever get adolescent sexual misbehavior to zero.) But it is far from clear that dismantling juvenile facilities and placing children back in the community will make them any safer.